In spring 2016 Cameron Diaz published The Longevity Book, the long-awaited sequel to The Body Book, a number-one bestseller in 2014. In her books the Hollywood star promises healthier, more fulfilled lives and more beautiful selves to those who follow her guidance. Diaz’s publications are recent additions to a growing corpus of advice literature published by actresses claiming expertise over the female body. Often this advice comes wrapped in a language of empowerment. In The Body Book, Diaz writes: “…nutrition and fitness…are not just words they are tools. They are power. They are ways to care for yourself that empower you to be stronger…and truer to yourself” (2). “Love Your Amazing Body,” the book’s back cover exhorts its readers. The tension between feminist rhetoric and the promoted hegemonic ideas of beauty and health create a powerful neoliberal narrative of the value of self-optimization. But while empowerment rhetoric has become an important tool in coercing women into subjecting themselves to hegemonic beauty standards, I argue that it simultaneously succeeded in expanding beauty ideals, and created an alternative space for representations of the female body.

On its cover The Longevity Book shows Diaz, posing allegedly without make-up. A growing number of celebrity women have recently posted their make-up free faces (#NoMakeup), claiming liberating intentions. But in a way, these images have raised the bar for non-celeb women. Make-up free insinuates effortlessness, acceptance, and ease with one’s appearance. But Diaz’s image features highlighted hair, groomed eyebrows, curled lashes and flawless skin that speaks of a healthy lifestyle, and expensive skin-care products. Her make-up free look can only be achieved with time, substantial commitments, and privilege, all of which is left invisible. Diaz’s books offer information and a positive perspective on the aging process. Diaz suggests yoga, meditation, and a conscious and active engagement with physical changes that takes money, time, and space for self-awareness that is beyond the reach of many American women today. But with her information on the impact of stress upon the body, ovarian cancer, and sleep deprivation, Diaz uses her reputation to circulate knowledge on women’s bodies and issues to a lay audience. Especially menopause-related issues such as depression and cognitive impairments receive little coverage in American pop culture, and are here given space to aid readers seeking information on these topics.

Since the 1940s actresses have been consulted on questions of body management as their appearance was taken as evidence for their expertise. Publications for girls and adolescents included recommendations from stars and starlets on slimming one’s waist, posture, and exercise. Before the 1970s, celebrity advice mostly uncritically endorsed hegemonic beauty ideals, but the women’s liberation movement and feminist discourse in the 1970s allowed to discuss feminine ideals more analytically. It also introduced empowerment as a rhetorical tool to sell products and ideology to a financially independent female audience. Jane Fonda popularized aerobics in the 1980s, today best remembered for pink leg warmers and revealing leotards. Aerobics led to a gendered commodification of workout routines, but by glamorizing it, it also appealed to a greater number of adult women to exercise. Jane Fonda’s Workout Book from 1981 reflects the contradictory messages disseminated by celebrity advice influenced by feminism. Fonda contextualizes her workout program within a greater critique of the ideals women growing up in the late 20th century confronted: “Like a great many women, I am a product of a culture that says thin is better, blond is beautiful and buxom is best” (9). In her introduction, Fonda discusses how culture and the women surrounding her taught her as a child about cohering to ideals of women: “I abused my health, starved my body, and ingested heaven-knows-what chemical drugs, I understood very little about how my body functioned, and what it needed to be healthy and strong. I depended on doctors to cure me, but never relied on myself to stay well” (9). Revealing her own history of bulimia and crash dieting, she states that doctors and other experts were complicit in abusing her body to fit an impossible beauty ideal. She recalls how doctors unquestioningly gave her prescriptions for amphetamines that she took to reduce her weight and led her into severe addiction (14-15). Fonda claims that the doctors she consulted neither questioned her overdosing on medication, nor educated her on possible side effects. The collaboration of expert advice, Hollywood, and beauty ideals led her to an alienation from her own body that, she claims, could be overcome only if women educate themselves and shift their concerns to their health, rather than beauty.

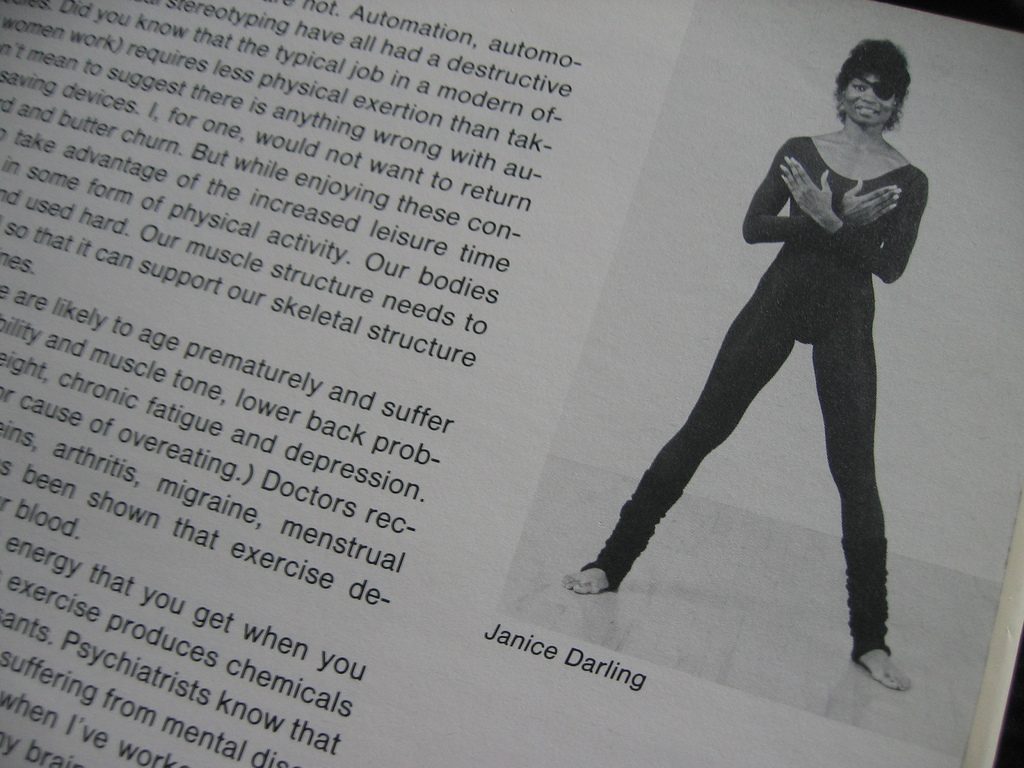

Janice Darling: The Pirate Gymnast, Photo from the “Jane Fonda Workout Book”, picture by Laurie Pink, via Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

This critique frames the actual workout routine broken down into step-by-step photos. These images show waif-like women with ballerina-worthy posture, hardly signifying resistance to hegemonic norms. The bodies are gently toned at most, and their femininity is accentuated by dance-inspired sportswear. Aerobics thus quietly reproduces, despite its stated focus on health and strength, the feminine ideal of the day. There are only a few moments in which the visual aids create an unexpected undercurrent: one of the photographed instructors, Janice Darling, an African-American woman, wears an eye-patch. As the text explains, she was hurt in a car accident, lost sight in one eye, and had her pelvis crushed and two legs broken. Against the predictions of doctors, she taught herself to walk again in record time and with the help of a rigorous aerobics routine and closely monitored nutrition (48). Her story exemplifies that women should become the experts over their own bodies and it promises success when they choose to do so. The images featuring Jane Fonda also expand the conventions of what constitutes beautiful female bodies in the 1980s, in the way photographer Steve Shapiro stages her. The camera moves away from lingering over her waist, breasts, and hips, instead Fonda’s biceps become the focus of her representation. Her arms are often at the center of the composition, are prominently displayed, or dominate it. Female muscle is here framed as beautiful, gently contradicting traditional representations of feminine beauty. Fonda stages her body as strong and capable rather than fragile and soft, concurring with changing gender norms that were more ready to acknowledge women’s strength, their growing financial power and political influence, as well as neoliberal demands to be responsible for one’s own health and wellbeing. But the text simultaneously utilizes the possibilities of the transitionary moment to expand the visual repertoire of how the female body could be depicted.

In their advice books, Fonda and Diaz may have created new ways in which the female body is disciplined to conform to hegemonic beauty norms, but they also offer an alternative space to discuss women’s bodies apart from traditional expert discourses. While hardly ever dismissing gendered beauty ideals, the texts expand them to include health and strength as desirable categories, and attempt to present a more holistic view of the female body, including issues such as menopause and bulimia. Celebrity advice is thus a potentially ambivalent genre representing female bodies at the crossing of resistance and discipline.

Joan Wagner says:

Thank you for your article . I took classes in Janice Darling’s studio, The Sweatshop, in 1983.

Her classes were amazing.

Do you have any information as to where she is now?

Thank you