Creamy, sometimes salty, and optimistically yellow, butter is one of my favorite foods. It’s also a scientific and cultural barometer. For the first half of the twentieth century, nutritionists enthusiastically endorsed butter as a good source of energy and part of a healthy, moderate diet. Early government-issued food guides endorsed eating enough food, as public health efforts focused on such problems a nutritional deficiencies and inadequate diets, particularly for children. Since then, increased food availability, changing disease patterns, and additional research have reshaped food and nutrition guidelines, changing perceptions of butter along the way.

Butter’s shifting nutritional status provides a window into major developments in dietary advice and public health. The following food guides sought to communicate each historical moment’s nutritional knowledge to various audiences. For readers today, these guides demonstrate how dietary advice speaks as it transforms over time.

1894: Foods: Nutritive Value and Cost

Commonly referred to as “the father of American nutrition,” Wilbur O. Atwater published “Foods: Nutritive Value and Cost” in the USDA’s Farmers’ Bulletin in 1894. This publication documented many of nutrition science’s key concepts. Although specific minerals and vitamins were not yet known, Atwater’s publication identified the calorie as food’s unit of energy. It explained that calories in food come from a combination of macronutrients: protein, carbohydrate, and fat. It also made nutrient recommendations based on activity level, and later differentiated between men and women. In this document, Atwater mentioned butter a delightful twenty-six times.

1916 and 1917: Food for Young Children and How to Select Foods

Building upon Atwater’s research, nutritionist Caroline Hunt published the first USDA food guide, Food for Young Children, in 1916. Hunt verified that “simple, clean, and wholesome food” ensured child health and development. Perhaps most surprising for today’s eaters, the guide recommended five food groups, one dedicated solely to sugary sweets and another to fats such as butter.

With Atwater’s daughter, Helen Woodard Atwater, Hunt published How to Select Foods in 1917, which presented these food groups for a more general audience. Continuing to emphasize advice to help folks eat enough, the authors wrote that sugary and fatty foods were important sources of fuel for the body. Music to our butter-loving ears, they wrote that without a little fat, “food would not be rich enough to taste good.”

1933: Food Budgets for Nutrition and Production Programs

During the hardship of the Depression, USDA head food economist Hazel Stiebeling published Food Budgets for Nutrition and Production Programs. The most financially restrictive of the four food plans provided a survival diet for a family of five that cost $22.85 a month. That’s the buying power of about $450 in July 2019, according to the US Department of Labor. The food plan included grains, potatoes, and dried beans or peas, aiming to provide emergency levels of calories, calcium, and vitamins A and C. The food plans with higher budgets recommended more milk, eggs, and meat. Servings of fats (including butter) remained relatively constant across all the food plans.

1943 and 1946: National Wartime Nutrition Guide and National Food Guide, A.K.A. the “Basic Seven”

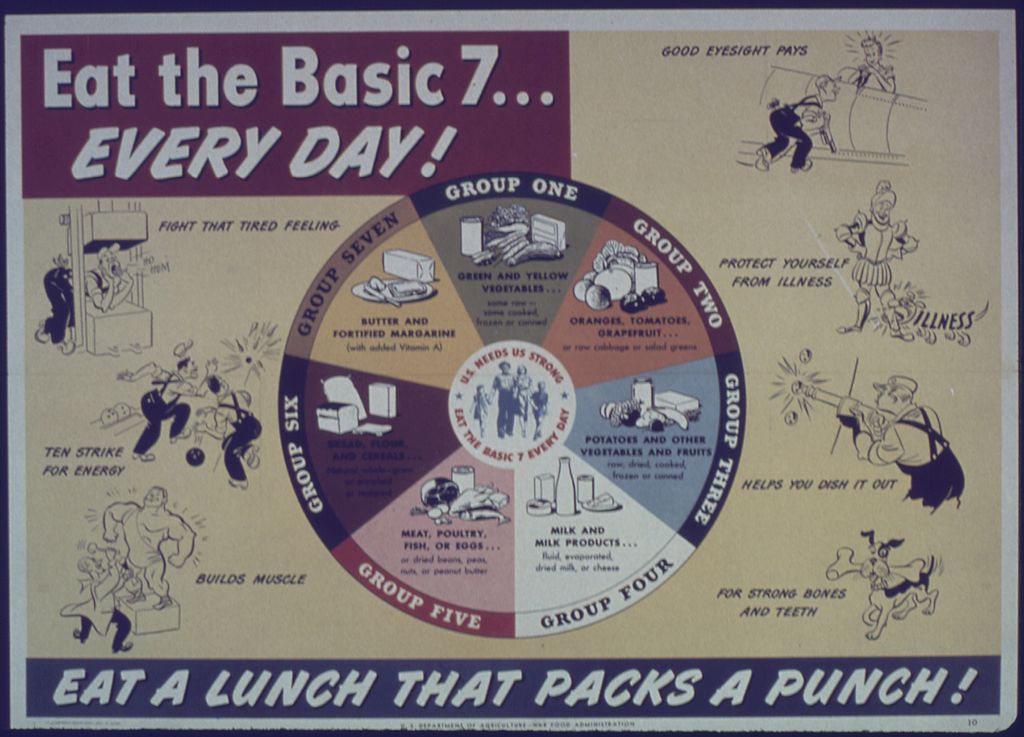

Published in 1943, the National Wartime Nutrition Guide was a foundation diet. It recommended daily servings from dedicated food groups, while still liberally allowing for other foods, like, well, butter. The guide was commonly known as the “Basic Seven” for its seven food groups, often depicted as sections of a circle. The guide assisted those on the home front to eat well even when certain foods were rationed or scarce. Reissued in 1946 as the National Food Guide, the Basic Seven dedicated an entire food group to butter and fortified margarine, recommending daily consumption.

1958: Food for Fitness — A Daily Food Guide, A.K.A. the “Basic Four”

Popularly known as the “Basic Four,” Food for Fitness–A Daily Food Guide replaced the Basic Seven in 1958 as a foundation diet. It remained in circulation for nearly twenty years. It recommended a minimum number of daily servings from four food groups: milk, meat, breads and cereals, and vegetables and fruits. It also made space for “other foods,” defined as “foods to round out meals and satisfy the appetite.” Butter topped the list.

The Basic Four didn’t directly mention weight or what we think of today as diseases potentially related to obesity. Concern for poor diets and nutritional deficiency diseases still predominated public health nutrition, as documented in “Some Recent Advances in Nutrition,” published in JAMA in 1958. As such, the Basic Four recommended that children should eat enough to “support normal growth,” and adults “need enough [food] to maintain body weight at a level most favorable to health and well-being.” (Butter is part of our well-being y’all.)

1977 and 1979: Dietary Goals for the United States and The Hassle-Free Daily Food Guide

The Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs published Dietary Goals for the United States in 1977. A departure from previous guides, it promoted avoiding excessive intake of specific nutrients that appeared to be linked to chronic disease risk and increased body weight. Dietary Goals set quantified recommendations for carbohydrate, fat, cholesterol, sugar, and salt. These recommendations built upon the Diet-Heart Hypothesis, which came to the fore in the years after the Basic Four. It proposed a potential relationship between saturated fat in the diet, serum cholesterol levels, and subsequent coronary heart disease.

The Hassle-Free Daily Food Guide communicated these recommendations to the public. It retained the four food groups of the Basic Four, but added a new group for fats, sweets, and alcohol as foods that “provide calories but few nutrients.” A yellow caution sign marked this group in the guide. This illustrated a clear change in how the government framed food consumption for the public and the connections between food, weight, health, and disease. This was when butter’s demise began.

1980 onward: Dietary Guidelines for Americans

Continuing on the nutrient-based path set by the Dietary Goals, a committee of experts released the first Dietary Guidelines for Americans in 1980. These guidelines have been reviewed and updated by a committee every five years since then. Expanding the scope of dietary guidance, the 1980 Guidelines encouraged maintaining “an ideal weight.” The Guidelines conceded “there is no absolute answer” to what that weight ought to be, but nevertheless claimed that most people’s weight should “not be more than it was when they were young adults (20-25 years old).” (UGH to that!) This focus on weight was purportedly triggered by the increasing prevalence of “obesity.” The specific recommendation to “avoid too much fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol” pounded another nail into butter’s coffin.

Based on the 1980 Dietary Guidelines, the Food Wheel: A Pattern for Daily Food Choices visually depicted six food groups and daily serving recommendations. The scantest slice of the wheel was for fats, sweets, and alcohol with no daily servings attributed. Butter’s downfall continued….

1992: The Food Guide Pyramid

The USDA developed the Food Guide Pyramid to increase public awareness of the Dietary Guidelines. It depicted food groups in a hierarchical arrangement with 6-11 daily servings of grains forming the base. Butter became a mere dot in the pyramid’s peak with the admonishment to “use sparingly.” While earlier buttery advice emphasized small amounts of fat for palatability, these recommendations focused more on weight management than flavor.

2005: The MyPyramid Food Guidance System and the Harvard School of Public Health’s Healthy Eating Pyramid

The MyPyramid Food Guidance System replaced the Food Guide Pyramid in 2005, but its conceptual design with vertical, colored sections was vague, confusing, and failed to catch on. It was, however, one of the first U.S. food guides to visually depict physical activity alongside nutrition recommendations with a stick figure running steps up the side of the pyramid.

Nutrition experts at the Harvard School of Public Health were so disappointed in both pyramid designs and the Dietary Guidelines behind them that they issued their own Healthy Eating Pyramid. Harvard experts argued that their guide better represented research on diet and health, particularly for healthy fats and whole grains.

In both the USDA guidelines and Harvard’s, butter was to be used sparingly, relegated to MyPyramid’s skinny yellow strip and to the Healthy Eating Pyramid’s top section.

2011: MyPlate and Harvard’s Healthy Eating Plate

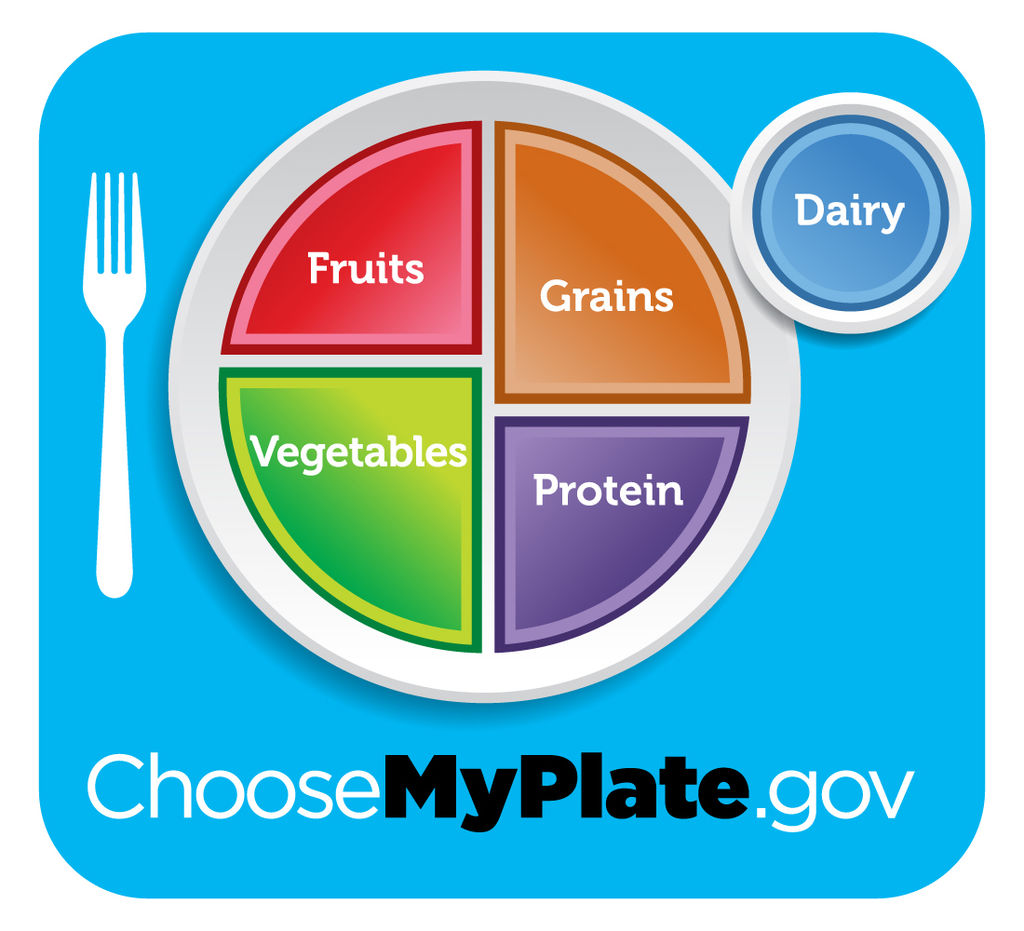

In 2011, the USDA did away with the pyramid altogether, opting for a dinner plate design, MyPlate. Harvard again presented their own version, which contested the USDA’s generous milk recommendations. On Harvard’s Healthy Eating Plate or MyPlate, there’s no dedicated place for butter.

2015: Dietary Guidelines for Americans

The 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans newly emphasized overall eating patterns, rather than specific foods, food groups, or nutrients. The Guidelines offer three USDA Food Patterns—Healthy US-Style, Healthy Mediterranean Style, and Healthy Vegetarian—though it’s debatable if they are any easier to follow than the tools the Guidelines provided previously. That said, the Guidelines still include quantified, nutrient-based recommendations for added sugars, sodium, and saturated fat (poor butter).

Conclusion, For Now…

As this buttery history shows, food guidelines are cultural artifacts. They tell stories about how the government, scientific experts, the food industry, and everyday eaters conceptualize diet, health, disease, and food—especially foods like butter. Through these many decades of food guidelines, we can witness scientific paradigms and social systems in the making and as they transform. Food guides have shifted away from early messages that encouraged Americans to eat enough food to stay healthy. In more recent decades, guidelines instead warn eaters to avoid specific nutrients (like saturated fat), to strictly control their weight, and, more recently, to adopt healthy eating patterns. Dietary guides have responded to changing health concerns. They have also spoken to food system and policy issues, such as the overproduction and easy availability of cheap and less nutritious food, alongside the relative underproduction of fresh fruit and vegetables. Food guidelines become part of our everyday food life, whether we follow them or not.

As for me, I’m still eating butter.

This essay by Emily Contois originally appeared on “Nursing Clio”, October 22, 2019. It is republished with permission by the author and the editors.