Free will is the basic concept underpinning liberal capitalism. But it was only put fully into practice in the 1980s, when the state divested itself of responsibility in many ways and individuals were prompted to voluntarily take responsibility for themselves. The ethical principle of self-responsible voluntariness penetrated every sphere of life. Interestingly, this was exemplified by a group whose autonomy appeared to be suspendible by statute—prisoners.

The German constitution or Basic Law repeatedly states that nothing should occur that is “against the will” of an individual. Free will is thus established ex negativo. The right to say no seems more important than the question of what exactly this will is. The Basic Law also states, just as vaguely, that everyone has the right to develop freely as an individual. In the early 1960s, the German legal system stipulated that this did not apply to prisoners because they were subject to a “special legal relationship.” When an inmate at the Celle Correctional Facility complained in writing during the Christmas season of 1967 about the miserable conditions at this institution and his letter was confiscated by the prison administration, he brought an action against this curtailment of his personal development. The case reached the Federal Constitutional Court, which then decided on March 14, 1972 that even those subject to a special legal relationship were entitled to basic rights and that a legal basis was required to restrict them. A corresponding Prison Act (Strafvollzugsgesetz) came into force on January 1, 1977.

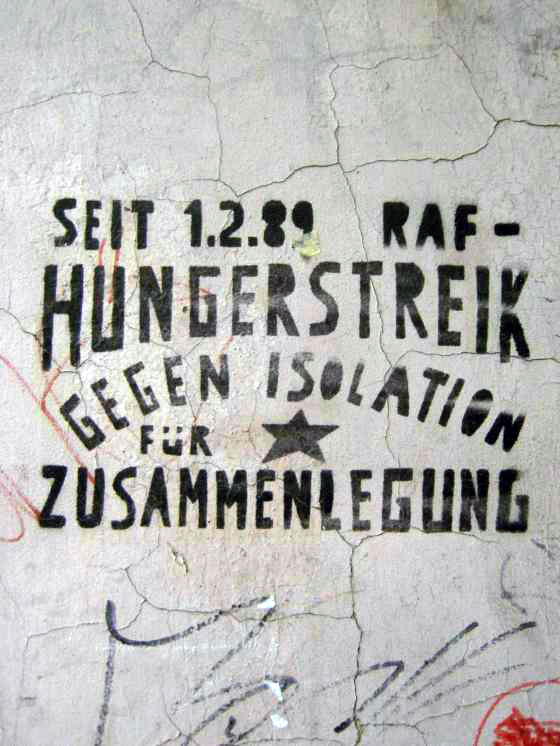

Free will is thus already restricted under conditions of detention (it is rare for prisoners to remain in custody voluntarily). Opportunities to protest against imprisonment are limited. In the 1970s and 1980s, imprisoned members of the Red Army Faction (RAF) tried to bolster their rights by means of hunger strikes in an attempt to link the improvement of prison conditions with the state’s recognition of a state of war. During these hunger strikes, the issue of free will was dealt with in a dual sense. Prisoners whose potential for personal development was limited refused to eat and were force-fed against their will. We might also refer to a “protective use of force” through which the state sought to keep those in its custody alive. However, this contradicted the precept that, other than in emergencies, the individual concerned must consent to every medical intervention. The clash between the hunger strikers’ freedom of decision and the medical duty to save lives created a dilemma. The Prison Act did in fact equate force-feeding with medical intervention. The painstakingly negotiated Section 101 stated that prison doctors were obliged to intervene medically against the will of the hunger striker if there was an acute risk of death. The brutal force-feeding, which was often poorly implemented, could not prevent the deaths of Holger Meins in 1974 and Sigurd Debus in 1981. As a result, during this period commentators, including many from within the legal and medical professions, emphasized the primacy of both hunger-striking prisoners’ free will and the medical profession’s autonomy, it being vital, as they argued, that the latter take precedence over raison d’état.

Of particular importance was the question of whether prisoners were really taking part in collective hunger strikes of their own free will or whether they were swayed by group pressure. Karl-Heinz Dellwo, who had been in prison since 1975 due to his involvement in hostage-taking at the West German embassy in Stockholm, which cost four people their lives, had formulated a kind of ethics of militancy whose scope of application included circumstances of detention. The imperative here was to “conduct yourself voluntarily as an illegal person, otherwise you will become what they want to make of you: a cretin.” Dellwo subordinated his actions to a rigorism in which one’s own life is not the absolute value. In line with this, with respect to the hunger strike of 1981 lawyers concluded that while this action was unmistakably subject to central control, individuals’ participation was voluntary. The hunger strikers championed the militant principle of “non-compliance” and refused the “compliance” so crucial to medical treatment. The concept of a “reasonable patient”, which was increasingly discussed in the 1980s and implied an individual who, having been informed by medical experts, participates in her or his treatment, referred expressly to the free personal development enshrined in the Basic Law. The associated primacy of autonomy became the key dogma informing bioethics and medical ethics, which were becoming institutionalized at the time, and was also explicitly applied to the situation of hunger strikers. The delicate situation of medical treatment consists in voluntary submission to someone else’s will. The relationship between doctor and patient exists within the field of tension between paternalism and informed consent, between the politics of care and the ethics of autonomy. Medical anthropology too has underlined the asymmetry between medical competence and the plight of the sick person, which must ultimately be neutralized through a “balanced partnership.” On this view, the patient must take responsibility for himself or herself, while the doctor must delegate responsibility to the patient. In the specific situation of force-feeding, then, raison d’état overrode the prisoners’ personal rights as well as the ethics of the medical profession.

This changed in the early 1980s. Crucial here was the situation of Irish Republican Army (IRA) prisoners on hunger strike in the United Kingdom. Especially under the conservative government of Margaret Thatcher, the ethical principle of patient autonomy was fused with the political decision to make no concessions to the IRA. The resulting decision to forgo force-feeding resulted in the deaths of ten hunger strikers in 1981. In West Germany, meanwhile, after a long debate, intensive care became mandatory if hunger strikers were no longer able to express their will. This was legally enshrined in 1985 by an amendment to the Prison Act, in which the criterion of “risk of death” was deleted and only free will remained. Medical intervention was required only when free will could no longer be articulated. Personal responsibility was not to mean letting people die.

During the ninth collective hunger strike by the RAF in the winter of 1984–1985, this new principle was, as it were, tested out experimentally when the hunger-striking Knut Folkerts was taken unconscious to the heavily guarded Hanover Medical School. In line with the so-called coma method, the hunger striker was subject to intensive care only when he could no longer express his free will. He was no longer force-fed, but his life was to be saved. One crucial question was whether Folkerts, having regained consciousness, remained voluntarily under medical treatment. But the doctors entrusted with his care also had to prove that they were acting voluntarily, that they were not subject to the will of the Justice Ministry and also that they recognized the hunger strikers’ free will. At the same time, however, they had to get Folkerts to accept the role of reasonable patient. The coma method could only work if the hunger striker, who had become a patient, voluntarily agreed to further treatment after regaining consciousness and, so to speak, put the militant practice of “non-compliance” on hold. Otherwise, the medical treatment would have had to be terminated. During the ten days that Folkerts spent in the intensive care unit, the pacifying potential of this power constellation became plainly apparent. Folkerts, who wanted to go on living, participated in his treatment and the state delegated its responsibility to the doctors and the patient himself. But that which appeared to be a case of saving a life through intensive care and of the reasonable patient’s self-responsibility, the militant prisoners inevitably viewed as a defeat. The weapon of the hunger strike had become obsolete.

The new liberal-conservative regime, which tied self-determination to self-responsibility, proved stronger than the prisoners on hunger strike managed to be in the mid-1980s. In this sense, the history of the coma method is also a significant event in the reform of the responsible-paternalistic welfare state, for which the Social Democratic Party stood in the 1970s. This was reform by means of the liberal-conservative dogma of the individualization of responsibility. The medical ethics principle of patient autonomy, which was formulated in a quintessential way in light of the debate on the force-feeding of hunger strikers, was one of the elements that underwent modification as rights and obligations were privatized, a process that went hand-in-hand with the reorganization of state interventions from the 1980s onward. Faced with a state that had relinquished responsibility for the lives of hunger-striking prisoners, even the voluntarily illegal were powerless.