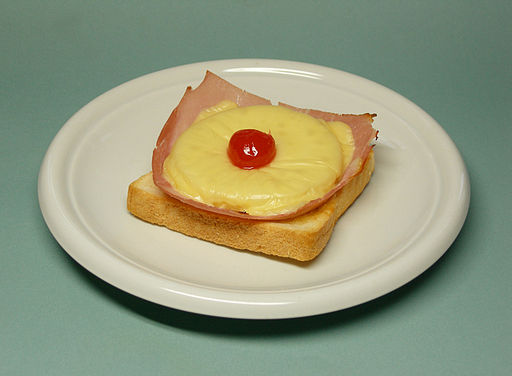

In the 1970s, Christmas Eve was divided between extremes. First, we had Toast Hawaii, like many other Germans in the Federal Republic: take a slice of sandwich bread, cover it with ham and a wheel of canned pineapple, top it with a slice of gleaming yellow processed cheese, bake it, and stick a bright red maraschino cherry in the resulting crusty indentation. Arranged on bread that, according to ‘low-food biographer’ Carolyn Wyman, was “tamed to be more palatable to a broader range of people from … the small kid to the adult,” Toast Hawaii was the stringy glue that held our nation together. An exotic feast for eyes and palate, it created a sense of belonging against all odds, even for a ten-year-old like myself. A child who was taller than most, switched between a southern dialect and Standard “High” German, and had a Low German family name that gave her away. Precariously fragile to begin with, my sense of belonging abruptly ended as soon as we unpacked my grandmother’s annual parcel. Coming all the way from Lower Saxony, it would include a small but heavy package of pumpernickel: 500 grams of black, crust-less rye bread, wrapped in cellophane to keep it moist.

The ten crumbly, thin slices had a sour and slightly bitter taste, conjuring up a letter written in 1586 by the Flemish humorist Justus Lipsius. He referred to pumpernickel eaters as an “impoverished people that is obliged to eat its own soil.” For my teenage self in sunny southern West-Germany, pumpernickel was not a class issue, but rather an act of communion: eating transubstantiated ancestral soil was a repatriation to a village up north that we rarely visited, a bleak, rainy and muddy place full of tales about relatives we never saw.

Like most stories about bread, this one is both personal and political: fundamental to the Western diet and the Christian religion, it pushed me towards the confessional mode. That I come from a family of atheists does not change this, but it replaces the metaphysical dimension of bread with an abysmal sense of loss. Who was I, and where did I belong? What is the cultural significance of the Toast Hawaii / pumpernickel divide and what does it tell us about (West) German society during the 1970s?

“Where Bread and Power Intertwine”

Even in secular environments, it is hard to imagine a narrative about bread that does not emphasize its role in forging bonds, including those between and within nations. Yet, while the French connect via baguettes and Americans via Wonderbread, Germans refuse to be subsumed under one kind of loaf. According to the Nationwide Inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage, there are 3200 kinds of bread in this country. On the occasion of the 2019 German Bread Day, Germany is defined as a broad “landscape of breads” rather than a single nation. Gone are the days when the German Bread Day logo took a variety of loaf forms and arranged them into the Brandenburg Gate, topped by a pretzel. The politics of German regionalism become apparent here when set against Lorraine Johnson-Coleman’s description of her famous BreadBook and the American South:

I was trying to dispel the notion of the South as just black and white. […] What you’re missing is that there are Italian Americans, Jewish Americans, Mexican Americans […] different cultures of people brought their own traditions to the South and mingled them.

The German emphasis on individuality and regional specificity excludes breads from immigrant cultures, an indication that bread is, as Aaron Bobrow-Strain has pointed out in White Bread, “more than just the stuff of sepia-toned sentimentality” and “has a more worldly and disquieting side; a side where bread and power intertwine.” Interestingly, this also applies to interregional relations. In 2012, the Vice-President of the German Bundestag, Wolfgang Thierse, demanded that Germans from Swabia curb their imperialist impulse and stop calling a Berlin roll made of wheat a Wecklebut a Schrippe. Bread becomes an issue when the cultural hegemony of wheat bread is seriously challenged by other grains. My family’s ritual affair with a particularly odd type of rye bread, pumpernickel, reaffirmed our status as Nei’g’schmeckte from Northern Germany – a less than welcoming dialect label pertaining to fellow Germans who taint the local cuisine with unbearable spices and flavors from the place where they originally came from (nei=into, schmecken=to taste; in dialect: to contaminate, cause illness, esp. via smells).

Unlike the Italian, Turkish, and Greek ‘guest workers’ who per definition were not meant to stay for longer, Nei’g’schmeckte were German enough to gradually infiltrate and destroy dearly-held local traditions and religious convictions. They had their children wear checkered pullovers over brightly colored synthetic turtlenecks to camouflage their otherness. But since they had grown up in a region where High German was the norm, they spoke the language of the know-it-alls and faultfinders. They fed their own wistfulness by sharing pumpernickel at the dinner table, thereby replacing what Lorena Graeter claims to be the spiritual center of southern German cuisine, a wheat bread known as Seele(= soul), with their dark, familial fare. By having Toast Hawaii on Christmas Eve, they reaffirmed their German-ness but stopped short of proving their membership in the regional host culture. Wavering between assimilation and defiant self-demarcation in a stubbornly conservative, change-resistant environment, Nei’g’schmeckte stuck out like the maraschino cherries on the silliest food in the world.

But how silly was it, really? Most of us were unaware that Toast Hawaii was a German invention, popularized by TV cook Clemens Wilmenrod in 1955. We wrongly assumed that it originated in the USA, like everything else that was yummy and a bit over the top. In the mid 1970s, those who had grown up in the 1950s passed it on to the next generations as a guilty pleasure that nostalgically evoked a better America, the liberator of 1945 whose dreams of economic and military influence in the Pacific had not yet reached Vietnam. Most were oblivious of the neo-colonial associations of the pineapple: coming from South America, pineapples became the Hawaiian signature fruit shortly after the U.S. had annexed the archipelago in 1898. In the early 20th century, corporations such as Dole and Del Monte started intensively cultivating pineapple; in 1922 James Dole bought an entire island and turned it into the world’s largest pineapple plantation. In some ways, the 1955 appropriation of the grilled Spamwich, which U.S. soldiers ate while stationed in Germany, was a celebration of American neo-colonialism, performed by those liberated: take the epitome of American food, adorn it with the token fruit of US imperialism, and plant a cocktail-cherry flag on top to signal ownership. Toast Hawaii was a playful wink toward their colonialism, and not ours (which Germans agreed was negligible).

It seems to me that until the late-1980s, (West) Germans were more willing to integrate under the unifying flag of an exotic other, than they were inclined to recognize regional differences as a source of cultural vitality. Today, the much-touted difference in mentality between northern and southern Germans has been replaced by bemoaning an unsurmountable east-west divide that involves dietary habits and excludes people with a “migrant background.” There is no simple recipe (!) to solve these conflicts. Interregional fusion food such as “checkered bread” or transnational blends such as “tramezzini with toast and pumpernickel” are not convincing, even at the symbolic level. So let’s bake some pumpernickel together, and recall what one commentator from Japan remarked after reading a description of it online: “Unfortunately, I don’t know if I can acquire this bread here in Japan. Anyway, I don’t think it’d have the same mysticism. Germany is an interesting country.” Its mysticism will be further discussed in a “sequel” to this blog entry, to be published here soon.