[I]t looks as though […] McKay has set out to cater for that prurient demand on the part of white folk for a portrayal in Negroes of that utter licentiousness which conventional civilization holds white folk back from enjoying—if enjoyment it can be called.

W. E. B. Du Bois, Review of Home to Harlem, June 1928 (359–60)

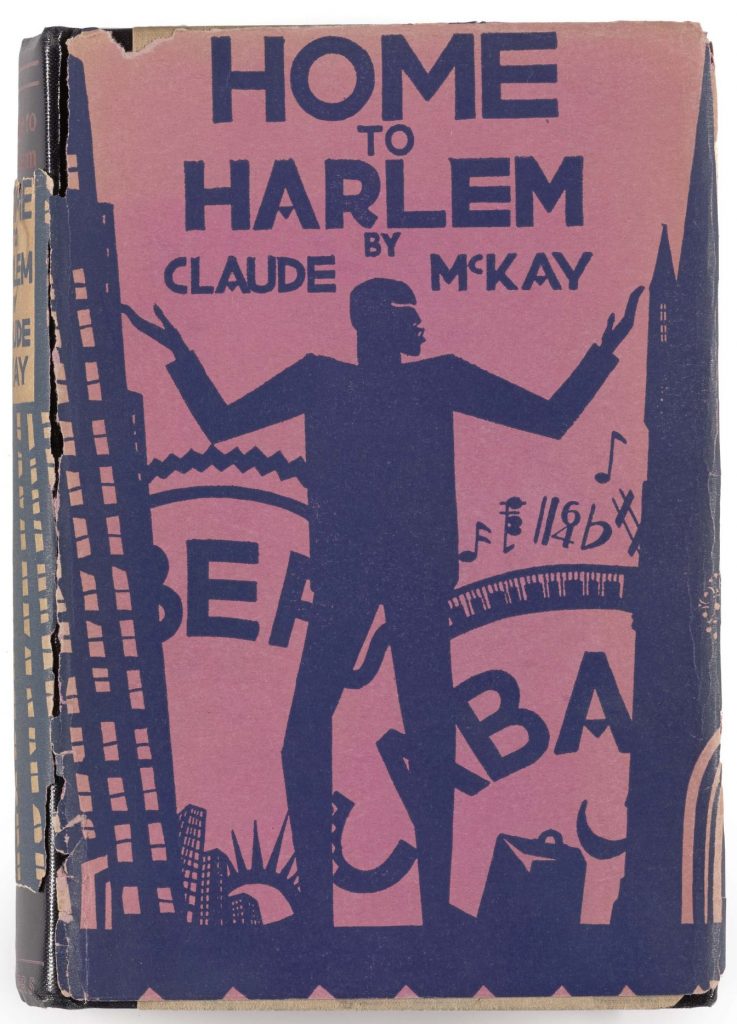

In 1928, W. E. B. Du Bois, sociologist, author, and one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, published a review of the younger Harlem Renaissance writer Claude McKay’s first novel Home to Harlem. He didn’t like it. He believed that the novel catered for white readers who wanted to see the wilder side of Harlem life: “drunkenness, fighting, lascivious sexual promiscuity and utter absence of restraint” (359), objecting ostensibly because the political cause of racial uplift would be negatively affected by too many stories about a black petty-criminal class. The phrases he uses—“utter licentiousness” and “utter absence of restraint”—describe the book’s approach to food cultures as much as they do its focus on criminality or socio-economics. Du Bois’s distaste, although possibly he did not recognise it as such, was in part an unease about the image of the licentious black character as glutton.

Home to Harlem, in its frank portrayal of working-class Harlem life, constitutes an intervention into discussions taking place in the 1920s about racial uplift and respectability, and part of its strategy for doing so is through the portrayal of its characters negotiating, in their different ways, traditions of consumption. In the late nineteenth-century, as Kyla Wazana Tompkins describes in Racial Indigestion, diet reform established itself as a civilizing and moralizing force opposed to the feared degeneration of the (implicitly white) race. Eating, she contends, is a “racializing practice”, and diet reform’s rhetoric drew on the “anthropological fictions of primitive and savage life that underwrote the United States’ self-fashioning as the nonpareil of white civilization” (73). Moreover, the physical effects associated with overindulgence, at least in terms of food, also constituted a racial marker in the late nineteenth and early twentieth-centuries. As Sabrina Strings argues in Fearing the Black Body, diet reform’s effect was that slenderness became “a marker of moral, racial, and national superiority’”(3); “Racial scientific rhetoric about slavery linked fatness to ‘greedy’ Africans. And religious discourse suggested that overeating was ungodly” (6).

McKay was aware of the racial overtones of this developing health discourse, and of Du Bois’s various attempts to combat the stereotype of the gluttonous African-American in his writings, but he did not agree with Du Bois’s implicit assumption that the way to rescue the reputation of African-American consumers was for the individual to repress their appetite or adopt a plain and uninspiring diet. In Home to Harlem he dramatizes the problems inherent in respectability politics’ suppression of appetite through his presentation of two chef characters: both black, fat and stigmatized for such; both possessing contrasting ideas about the foods they cook and eat.

First there is Susy, a matronly woman who briefly acts as sexual ‘ma-ma’ to the protagonist Jake’s friend Zeddy:

“[S]he belonged to the ancient aristocracy of black cooks, and knew that she was always sure of a good place, so long as the palates of rich Southerners retained their discriminating taste.

Cream tomato soup. Ragout of chicken giblets. Southern fried chicken. Candied sweet potatoes. Stewed corn. Rum-flavoured fruit salad waiting in the ice-box…. The stars rolling in Susy’s shining face showed how pleased she was with her art.

She may be fat and ugly as a turkey, thought Jake, but her eats am sure beautiful.” (175)

And here is the second chef character: a man described as “repulsive,” who cooks on a railroad dining-car. He has “elevated bulk,” “gross person” and “sloppy mouth,” but:

“[T]he chef had a violent distaste for all the stock things that ‘coons’ are supposed to like to the point of stealing them. He would not eat watermelon, because white people called it the ‘n—’s ice-cream.’ Pork chops he fancied not. Nor corn pone. And the idea of eating chicken gave him a spasm. Of the odds and ends of chicken gizzard, feet, head, rump, heart, wing points, and liver—the chef would make the most delicious stew for the crew, which he never touched himself.” (213-4)

In both of these descriptions the important things the reader needs to know about each character are communicated through racialised ideas about food heritage and identity. Susie claims her heritage from Southern “mammies”: enslaved women who cooked for white Southern families. Her skills and her food heritage are valued, and she does not, in her highly gendered as well as racialized “mammie” role, need to think about the politics of food traditions. The railroad chef is, conversely, completely estranged from these foodways. He knows that pork and chicken, particularly chicken offal, are cheap and therefore are coded Black. At Susie’s place this is not a problem, and the food is celebrated, but for the dining-car chef, a man sensitive to power structures, the foodstuffs themselves are untouchable because coarsening. Black food is savage food and white food is civilized food; there is a lot at stake for the Black eating subject.

While the two chefs are presented, in their diametric positions, in order to show how polarising the politics of food can be, the main character Jake is shown to be a kind of solution to the dilemma. Jake has a much more relaxed approach to food cultures. Just in the first few pages of the novel heconsumes martini cocktails, a “Maryland fried-chicken feed—a big one with candied sweet potatoes” (143), Scotch and soda, an affectation he has picked up in London—‘“English folks don’t take whiskey straight, as we do”’—then “hot coffee and cream and doughnuts” (145) in the morning quickly followed by “Fricassee chicken and rice. Green peas. Stewed corn” and later a “cocoanut pie” at “Aunt Hattie’s chitterling joint” (147). Jake later frequents European delis and eats “ham, mustard, olives and bread” and “chocolate-and-vanilla ice-cream and cake” (282). Jake eats, and enjoys, food from anywhere and everywhere. He doesn’t limit his pleasure to either racialized inheritance or to a narrow idea of Du Boisian respectability politics. In his carefree internationalism and unrestrained eating Jake negotiates not only his right of access to multiple foodways but his identity as modern subject; he demonstrates that he is able to perform cosmopolitan sophistication and thus enters a hypothetically non-racialised class of consumers.

Du Bois may have been disgusted at the “utter absence of restraint” in the characters’ attitude to sex, dancing, and eating, but McKay doesn’t recognise “restraint” as uncomplicated sign of a superior and civilised subject. Home to Harlem, then, is McKay’s first attempt at overturning what he saw as stultifying and counterproductive narratives of respectability, restraint and moralistic reform thinking. He posits a middle-ground between the black consumer who is afraid to eat unrestrainedly and polices his food in terms of its symbolic value and the black consumer who eats unabashedly and is not afraid to conform to stereotypes about greed and the unrefined palate. In McKay’s view “restraint” is an imposition from white respectability on the black subject; freedom is in part liberation from the directive to do less, be less and feel less. Jake’s joyful eating is thus an act of subversion.