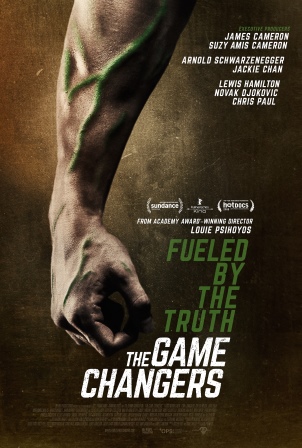

The controversial documentary The Game Changers seeks to debunk the myth that plant-based proteins will never be as good as their animal counterpart. For those who have not seen the documentary, a quick look at the film poster might help to better understand what is at stake here: in the documentary, vegan athletes are depicted as so ultra-masculine that they also make their dietary choice “manly” and, therefore, do not challenge hegemonic ideals of masculinity.

We see a strong arm, a clenched fist, and enlarged veins with green blood circulating through them. Next to this arm, green and white letters proclaim: “Fueled by the Truth: The Game Changers.” At first glance, the poster seems to announce a remake of the Hulk character: big, strong, and ready to fight—but appearances can be deceptive. This deception is at the very heart of The Game Changers because the documentary is not only about the health benefits of a plant-based diet but also about demystifying meat-eating as the key to success for professional athletes. In short, the documentary advertises a plant-based diet in order to enhance an athlete’s performance and his overall health condition. But not only that! On closer inspection, The Game Changers brings together fitness, nutrition, and the dominant model of being a “real” man (read: being aggressive, competitive, prone to sexual conquest and prowess, and normalizing risk-taking behavior such as fighting).

Fitness and nutrition have been intrinsically linked to each other in such a way that the “athletic” body runs mainly on the right composition of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. This is the reason why the athletic body needs to be fueled correctly in order to be competitive and to perform at its best. In Western societies, the myth that plant-based proteins will never be as good as their animal counterpart has been holding up successfully. This is the reason why a vegan body is usually viewed as deficient because it lacks the “powerful” protein, which seems to be the only “right” fuel for the professional athlete.

Bodily practices such as meat-eating are closely linked to masculine identities. In her ground-breaking book The Sexual Politics of Meat, Carol Adams points out that, historically, “people with power have always eaten meat” (48). This power—ingested in the various forms of meat—confers its very maleness to men. Thus, meat and its consumption are symbols of power and, correspondingly, meat-eating has been acquiring hegemonic status for men over the course of time. In patriarchal societies, meat has always been at the very top of a more or less rigid food hierarchy, whereas the feminized consumption of vegetables has been at the bottom. Although this food hierarchy is in constant flux, the norm of the meat-eating man seems to persist solidly. Consequently, men who adopt a plant-based diet are not considered “real” men in the hegemonic sense of the word because they lack the power that meat would have bestowed upon them. They actually run the risk of being emasculated within a dominant meat-eating society (57). Adams further suggests that, by eschewing meat, men can subvert the structures within dominant meat-eating society (63). At this point, though, I wonder whether this is actually the case. Which structures are subverted? And do vegetarian and vegan men really challenge the notion of what it means to be a “real” man in a “meatcentric” society?

Quickly after its release, The Game Changers was heavily criticized: it was accused of scientific inaccuracies, biased opinions about the health benefits of a plant-based diet, and lobbying for the consumption of vegan products, just to name a few. What is interesting to observe, however, is that, since its release in 2019, the documentary’s depiction of a hegemonic model of masculinity has not been criticized. The vegan athletes in The Game Changers readily adopt the main attributes associated with heterosexual men, such as strength, endurance, sexual prowess, and fertility. In The Vegan Studies Project: Food, Animals, and Gender in the Age of Terror, Laura Wright coined the term “hegan” in order to describe this phenomenon (126). “Hegans” do not only eat plant-based diets but they are so ultra-masculine that they also make their dietary choice manly. In other words, “hegans” masculinize a historically feminized and therefore marginalized diet. The sociologist Mari Kate Mycek conducted a study that yielded the result that vegan men would rather masculinize their eating habits than assume feminine qualities (225). She further identifies two discursive strategies that justify the decision of adopting a plant-based diet. On the one hand, hegan men adopt what she calls “rational discourse;” on the other hand, they follow “research-based motivations”—and both strategies are linked to masculine characteristics such as logic, rationality, and reason (230-31). The Game Changers makes use of these strategies in order to make a vegan diet socially acceptable for men.

The Game Changers is directed by U.S.-American photographer and documentary film director Louie Psihoyos. The documentary’s narrator is professional Mixed Martial Arts fighter James Wilks. At the peak of his career, Wilks was heavily injured. Confined to bed, and wanting to get out of it as soon as possible, he starts studying peer reviewed science articles on recovery and nutrition. At one point, he comes across a study about Roman gladiators and learns that they were predominantly vegetarian. Surprised, Wilks utters: “To think that the original professional fighters ate mainly plants went against everything I’ve been taught about nutrition.” From this point onwards, Wilks’ story-telling leads the audience around the world pointing out the benefits of a plant-based diet. Being on a journey to find the best diet possible for professional athletes, he encounters vegan athletes, scientists who favor a plant-based diet, and animal rights activists. The documentary is a combination of interviews, scientific studies, and experiments. Wilks is depicted as a hyper-masculine man who has the ability—thanks to this hypermasculinity—to resignify the historically feminized and marginalized plant-based diet and he does so convincingly. But instead of transcending the common notion of vegan men (read: not fit, not strong, not healthy, and not heterosexual), he resignifies the vegan diet by remaining complicit to the hegemonic ideal of how a “real” athlete is supposed to look, to perform, and to act. He reinforces this heteronormative ideal to the extent that other vegan men also desire to embody it. By doing so, Wilks engages in the gendered and sexualized elements of dominant meat-eating society. Vegan men are depicted as even bigger, stronger, and better than their carnivorous counterparts. As a consequence, he does not really subvert the notion of what it means to be a “real” man, but rather maintains a hegemonic status by reproducing the heteronormative system of power. Thus, Wilks acts like a “hegan” because he reinforces the hegemonic ideal of masculinity by reiterating carnivorous fantasies of physical prowess in a plant-based diet.

In the documentary, masculinizing a plant-based diet does not result in changing the relationship between food, gender, and sexuality. Since all athletes are depicted as strong, powerful, and dominant, they perform as “hegans.” The vegan athletes challenge the culinary norm of what a “real” man is supposed to eat, but they fail to challenge the hegemonic and heterosexual norm of how a “real” man is supposed to look, to perform, and to act. They challenge the “meat-eating versus plant-eating binary” but they do not challenge hegemonic ideals of masculinity. While Adams’s thesis that “people with power have always eaten meat” does not apply in The Game Changers, the documentary merely exchanges meat with plants without disrupting the logic of power: “people with power eat plants.” In this hegan context, men only disrupt the “meat versus plants dichotomy” but they leave the gendered and sexualized meanings attached to this dietary choice firmly in place.

Benjamin David Steele says:

I’m a left-liberal tree-hugging hippy who was raised in touchy-feely new agey religion. Specifically, it was the Unity Church, the same Church that Marianne Williamson is a minister in. They were doing same sex marriages when I was a kid in the 1980s. And going back to the early 1900s, the Unity Church, like the Seventh Day Adventists, actively promoted vegetarianism which included providing free vegetarian meals to nearby workers in Kansas City MO.

In my 20s, I became a vegetarian for a brief period, after my two older brothers had gone vegetarian, my oldest brother having done so when he became involved in the Hare Krishnas. At the time, we were all living in Iowa City IA, a liberal college town. It’s the place I spent part of my childhood and, after moving back after high school, I’ve remained in Iowa City. I’ve known many vegetarians and vegans here. One of my roommates was a vegan.

I’ve always been masculine in a basic sense, in that I’m athletic and have a high pain threshold. As a child, I was always a rough-and-tumble boys’ boy. But as the third male child, my mother was hoping for a daughter and she already had a girl’s name picked out for me. Though I’m not sure what affect this had on me, I was also always a momma’s boy and would help out in the kitchen. On top of that, I have strong emotions and, in Jungian terms, I’m dominant Feeling.

I’ve never really been all that concerned about my masculinity, neither interested in proving it nor fearing it being challenged. Certainly, it never occurred to me to think of diet as an expression of gender. That seems like such a strange thought. My parents raised me to eat meat, but it was always in moderation. My new agey grandmother had much influence on my mother in instilling health-consciousness, such as reading Prevention magazine. Back then, health meant eating ‘balanced’ low-fat meals that included vegetables and always washed down with a glass of milk.

Yet I grew up exposed to mainstream American culture. I’m fully familiar with the general obsession with masculinity. It’s just that I never fit into that culture. Even so, I never stuck with vegetarianism, as it didn’t help with my physical or mental health, although to be fair I was not doing the most optimal form of vegetarianism. My brothers, however, still are vegetarian and it’s a non-issue in the family.

When I’m around vegetarians, I eat vegetarian. But in my own diet, I’ve gravitated toward traditional foods, paleo, keto, and carnivore. I simply feel better keeping my carbs low, especially as a former sugar addict, and keeping my animal-based nutrient-density high, not only meat but also eggs and dairy. It hasn’t been an identity issue for me and I’m not dogmatic about any of it.. It’s simply a practical matter of what works through experimentation and experience.

I honestly don’t know how many people embrace diets for reasons of ideological identity and/or social identity. But in my personal observations, it doesn’t seem like identity concerns motivate most people. Those most motivated by ideology, of course, tend to be vegetarians and vegans. I’ve known more people on those diets for ethical/moral reasons than for health reasons. It’s funny that I also have a ‘vegan’ aunt who, following doctor’s advice, now eats fish; but for some reason identifying as ‘vegan’ remains important.

Here is an interesting thing. I came across a book exploring diet and ideology. The author discussed various diets, including paleo which she spoke of in terms of masculinity. But that doesn’t entirely fit my experience. Sure, there are plenty of masculine paleo advocates, but it doesn’t tend to attract hyper-masculine bodybuilding types, as it emphasizes a general healthy lifestyle of practical exercise, family, community, etc.

Part of the reason is that paleo is seeking to re-create not only an evolutionary-based diet but also an evolutionary-based lifestyle, as determined from archaeological and anthropological studies. It does not promote a Western ethos of hyper-individualism, if anything the opposite. A central message in the paleo community is how to be helpful to others. So, the type of exercises promoted are those that would make one generally healthy so as to help others.

Another contributing factor is the work of Weston A. Price as promoted by Sally Fallon Morrell. That falls under the broad rubric of traditional foods, whereas paleo (i.e., hunter-gatherer) is simply one variety of traditional foods. A major focus of the traditional foods is also family but also parenting, including a major concern for the health of mothers and children. Price and Morrell are some of the main influences on paleo.

The point is that, despite the caricature of paleo advocates as hyper-masculine meat-eaters, a large part of the community is female and even the males attracted aren’t muscleheads. In looking at some copies of the Paleo Magazine I had, I noticed that most of the contributors, editors, etc were women. So, where did the masculine stereotype come from? Even in the carnivore community, about half of the leading advocates are women.

Most people get involved in the carnivore diet, in particular, for health reasons. It’s one of those diets people tend to turn to when they have serious health problems, often life-threatening diseases, and even then only after trying every other diet. A large number of leading paleo and carnivore advocates are former vegans and vegetarians. So, it’s obviously complicated. Yet, as you point out, it’s interesting that the The Game Changers documentary falls back on masculine stereotypes to make its vegetarian argument.