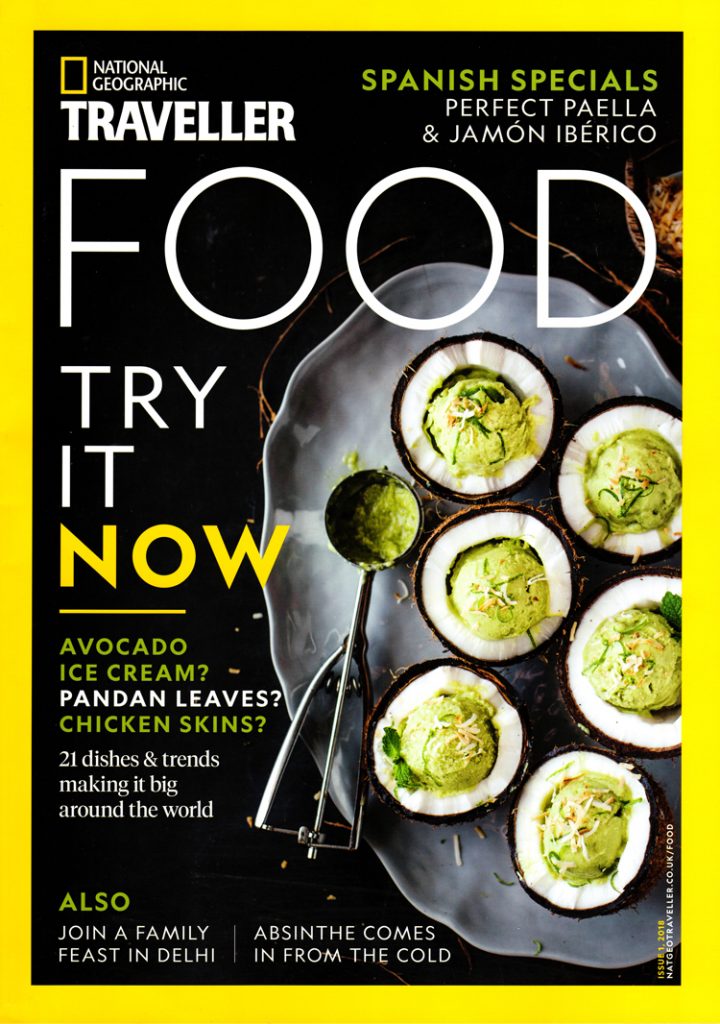

Food and eating are everywhere: in the blogosphere, in bookstores, on TV and streaming platforms, in social media such as Instagram. Nearly all newspapers, large and small, have cooking sections or extra food editions, and the portion of food-related print magazines has expanded hugely over the last years. The “foodie” has even become a characteristic social figure of our time, much like the “flaneur” of the emerging urban metropoles of modern society at the turn of the 19th century, or the “nerd” as the prototype of the emerging digital revolution during the 2000s.

What does the “foodie,” then, stand for? Is it a coincidence that we seem to be somewhat obsessed with food, eating, and cooking? I don’t think so. Rather, I suggest that we can understand the current omnipresence of food, cooking, and eating in the cultural sphere of the Global North as the expression of a specific politico-ethical ideal: The post-essentialist cosmopolitan subject, an updated version of neo-colonial authority. The “chef”—be it a professional cook or an amateur expert (a “foodie”)—is a master of sorts, who derives his or her authority from the ability to embody a paradox: To simultaneously acknowledge the relevance of, and even appreciate, sociocultural differences (such as gender, class, ethnicity) and to situate him- or herself above and beyond precisely these social differences. In other words, the pop-cultural serving of food and eating performatively (re-)enacts a sovereign self who is difference-savvy by mastering differences instead of being dominated by them.

Cooking and baking shows are a main stage for the enactment of the “chef.” Such shows come in two main genres: Those dealing with mobility and discovery, showing cooking and eating as urban adventure travel, and those staged as casting-voting-jury formats. The travel and documentary formats are those in which one more or less well-known someone—a chef, an actor, a travel journalist maybe—visits more or less well-known restaurants in more or less well-known places around the world: “Around the world in 80 meals” is how the intellectual German-French TV channel arte titled one of such series, evoking of course the emblematic Phileas Fogg in Jules Verne’s novel from 1873. Or, as a blog put it in praising the show, “A Cook Abroad”: “Each episode follows a different host as they traverse different parts of the world. From Sikh chef Tony Singh’s trip to India to motorcycle enthusiast Dave Meyer’s jaunt to Egypt to Rachel Khoo’s inspiring look at Malaysia, it’s easy to see the adventurous appeal of the series.”

Such “adventurous” travel-food series and shows are a neo-colonial mise-en-scène of identity politics, bringing multiculturalism to a hungry audience in the Global North, staging food and its where’s and how’s as multiple materializations of distinct cultures. And these are cultures to be consumed by the spectators, but only after the specific food, its preparation, and eating rituals have been checked and appropriated by the Master of Cultural Food Ceremonies. He—extremely rarely a she, which is by no means mere coincidence—is literally the chef/master, the one assessing things for his audience; a heroic master, as adventurous as he is accomplished. We, the audience, are introduced to new flavors and spices, aka a new culture, through the master’s mouth, knowing this new experience will be safe for us to consume, its pinch of spicy novelty included.

In such shows, entire countries or specific cities are presented as different through their food and by how it is prepared, served, and consumed: ”If you want to know what Israel is really like, you gotta come here. Walk the streets. Meet the people. Eat the food,“ says Phil Rosenthal, the US American, white, middle-aged, heterosexual chef-master (actually, Phil Rosenthal is a screenplay author, specializing in comedy series) who travels the world eating local and meeting locals. The take-home message is that Buenos Aires differs radically from Stockholm, Hong Kong from Tel Aviv, Cape Town from New Orleans insofar as the food and all related habits differ.

But such cultural culinary ontology does not necessarily imply incommensurability. On the contrary, many travel-food shows stress the overall similarity of cultures, bridging cultural-culinary differences through references to a universal humanity and global sociability that—at the end of the day—is inherent to all truly good food and an authentic joy of eating. In “Somebody feed Phil,” a visually high-end Netflix production, the chef-master constantly comments on the humanist value of embracing difference as part of universal humankind—he repeats the cosmopolitan mantra, ”we’re all different and we all love our own food as much as sharing it with all others.” This, in a nutshell—or rather, on a bbq grill, in a sandwich, in a chocolate cake—is the quintessential liberal cosmopolitan standpoint: A habitus that cherishes innate cultural differences and assimilates them through incorporation and with the acknowledgement that, in the end, we are all human and, thus, the same – united in the shared comfort of universal noshing, smacking, slurping and chewing. Of course, Phil or the other chef-masters are not interested in food inequality, in the specific working conditions in the cafés, restaurants, or food markets they enjoy wherever they travel, nor in any other economic aspect of the joy of eating.

The second variety of food shows is the casting, reality-competition format. Here, the preparation of food is staged as a series of challenges, and the results are judged by professional chefs. Amateurs with evident cooking skills or semi-professionals—foodies—are cast to participate, competing against each other by mastering the specific cooking challenges posed by the jury. In “The Taste,” aired in the US (2013-2015) and Germany (2013-), each season begins with blind auditions of amateur or semi-professional cooks. Several judges, all well-known and haute cuisine chefs, taste one spoonful of food from each contestant. Based on their impressions, each member of the jury decides which contestant is to be on his or her team. After the contestants are chosen, each episode of the show consists of a mix of individual and team challenges, all related to cooking and presenting food. As with other casting formats, what is actually judged through the assessment of cooking are a variety of individual traits that the competitive setting has brought out: skills, effort, abilities, and capacities. Interestingly, the German version of the show takes care in presenting a diverse cast—different ethnicities, skin colors, ages, regions, sexualities, genders, etc.—and stresses the multiculturality of the food itself. The challenges include preparing a broad range of “regional cuisines,” often represented through specific ingredients the contestants have to cook with. Judges and contestants alike often use regional/national or ethnic labels in regard to food, e.g. “Asian,” “German,” “Mediterranean,” but also “fusion,” “crossover,” etc.

In “The Taste,” the mastery of differences is key. Knowledgeability is expressed through the lingo of cultural differences and the mastery to playfully mix them. The Chef is the ultimate authority insofar as he or she assesses the capacity of the contestants to understand (cultural) differences and to strategically master them. This logic is, no surprise, precisely the hegemonic form that neoliberal capitalism has taken when it cherishes diversity and encourages us all to be and think “different”—as long as these differences, and their performance, remain ideologically stripped of their inherent inequality and power structures. The Chef is the boss.