The burek – a pastry made of phyllo dough with various fillings, well-known in the Balkans, in Turkey (bürek) and also in the Near East by other names – probably arrived in Slovenia in the 1960s. Industrially, the most ambitious of the Yugoslav republics, Slovenia needed a workforce. And with that workforce – immigrants from the former Yugoslav republics – came the burek. To paraphrase Max Frisch: We called for a workforce and we got bureks!

But the burek might have remained unknown to the majority of Slovenes if not, in the 1960s, “foreign” burek stands (run by Albanians from the former Yugoslav republic of Macedonia) appeared in various Slovene towns with high concentrations of immigrants or soldiers. Until the 1980s, this street burek remained almost exclusively immigrant food. But from the moment that Slovene mouths first bit into the burek, the story of the burek very quickly became more complex, richer, meatier. In the second half of the ’80s the burek reached the podium, at least in the larger Slovene towns, and perhaps even became the winner of the fast-food Olympiad. By the end of the ’80s some “Slovene” bakeries were beginning to make bureks; this trend has increased to the present day. According to a technician at one of Slovenia’s largest commercial bakeries, the burek has become the number-one selling item. In the mid-1990s the burek entered the Slovene nutritional mainstream. Since then, it has taken its place among the leaders both in terms of quantitative growth and expansion into new areas and institutions: it is served in the Slovene army; it is stealing shelf space in Slovene supermarkets; it has made its way into Slovene schools, parties, shows, and even onto flights of the Slovene national airline and it hasn’t stopped there. Since 2013 it can be purchased with a filling made of Carniolan sausage (the flagship of Slovene cuisine) under the name “Carniolan” burek (Carniola was a central – and the most “Slovene” – part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the adjective is now used to grace many things that are considered to be Slovene par excellence).

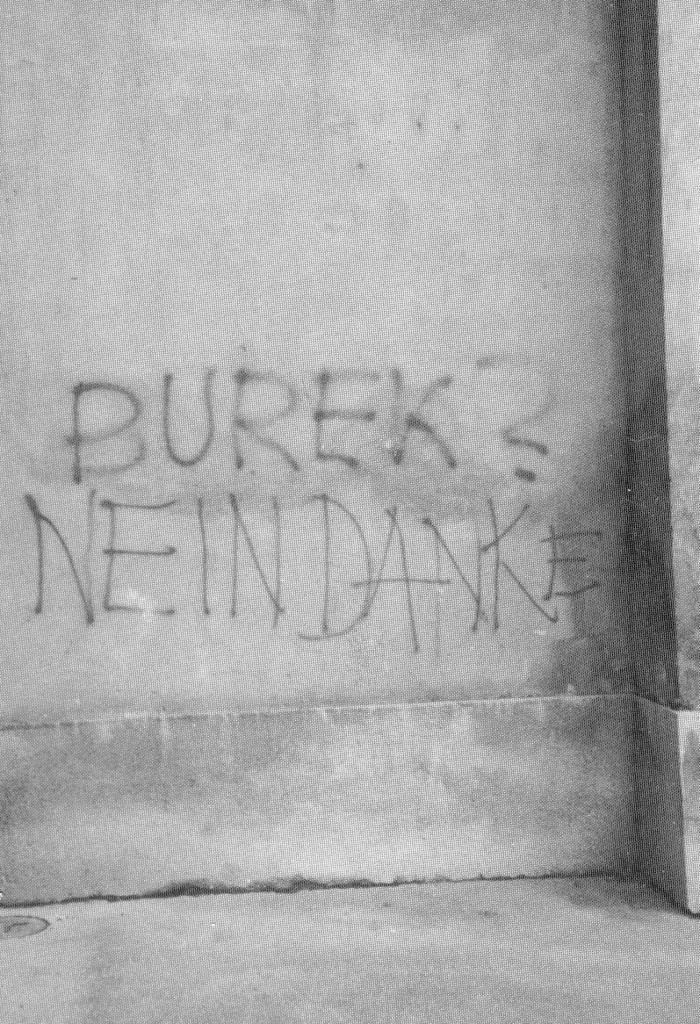

“Burek? Nein danke,” probably Slovenia’s most frequently reproduced graffito. Photo courtesy of Aleš Erjavec

The burek has not just conquered Slovene streets, schools, shops, kitchens and numerous other public and private places and non-places, but has also left its greasy mark on the Slovene language. Today it has a privileged place in Slovenia as a loaded metaphor for not only immigrants and Southerners, but also for the Balkans, the former federal republic (that is, Yugoslavia) and the phenomena associated with it. No doubt, it’s likely the best-known, and to a great extent even the most assimilated, but still the most widely debated immigrant in Slovenia. Moreover, it has become the most convenient signifier of unhealthy or greasy food. Without the burek both the mindscape of Slovene nationalism and the rhetorical arsenal of promoters of healthy lifestyles and health food would be significantly poorer.

The burek has therefore greased not just Slovene hands, mouths and streets, but has also smeared the Slovene language. It is precisely its immigrant status which has to the greatest extent shaped its current meaning in Slovenia. Let me list only a few of the more noticeable media and pop-culture roles played by our rolled (or folded) hero, filled with all sorts of fillings, increasingly enjoying the status of a naturalized immigrant: “Burek? nein danke,” probably Slovenia’s most frequently reproduced graffito, which appeared in a street of the Slovene capital Ljubljana in the second half of the 1980s and has occasionally reappeared on the town’s walls since; “Burek? Ja, bitte,” the title of at least two articles in prominent Slovene newspapers; “Anti Burek Sistem,” the name of a project by a Slovene skinhead group; “I’ll have a burek, but not a mosque,” another popular Slovene graffito; “you don’t have enough for a burek,” a very frequently used slang expression meaning “you have no idea” or “you’re clueless” and the similar “you’re a burek” or “you’re a burek squared”; Burek.si!?, an academic paper written by the author of this text (a.k.a. “Dr. Burek”), which owing to the simultaneous “triviality” and “significance” of the object of study sparked numerous discussions and responses among the general public …

But why and how has this edible immigrant become a hero? How has it become so well-known and widely discussed, and how has it come to represent all immigrants and all of the former republics of the SFRY? In other words, why and how has the humble burek, about which the Lonely Planet guide to the Slovene capital Ljubljana gives you the “greasy lowdown”, managed to grease the Slovene language, culture and society?

According to people’s memories and newspaper articles, the burek began to be eaten by non-immigrants in the 1980s. These early Slovene burekeaters were primarily university students and other urban youth who had not been sucked in to the nationalist euphoria and/or Yugophobia. This means that the burek began to signify not only ethnic differences (between “Slovenes” and “non-Slovenes”), but also those Slovenes who did not have any major problems with the presence of immigrants from other republics of former Yugoslavia. Here we have to be clear about one thing: According to conversations with numerous urban vagabonds, protagonists of the 1980s urban subcultures etc., in those times the burek was not a sign or a symbolic object within various subcultural groups, nor was it a significant, important part of subcultural consumption. The great majority of people who did or did not eat bureks in the ’80s didn’t see it as an explicitly political gesture. For burekeaters it was a source of calories, not symbols.

At any rate, the burek made it possible to get something warm to put in an alcohol-laden stomach, something cheap for shallow pockets and something that was available even at the oddest hours in the still very modest “socialist” range of products and services available in the ’80s. In those times, in the majority of the larger Slovene towns, bureks were almost the only warm food available late at night and in the wee hours of the morning. And this is probably the decisive – though not the only significant – impetus in the burek’s march onto this stage of signifying, discourses and nationalism.

The crucial point of this early bureknarrative of consuming “calories without symbols” is therefore that the “immigrant,” “Balkan,” “southern” burek found its way onto Slovene streets, and worked its way into the hands and mouths of the “indigenous” population, “Slovenes.” The fact of this “non-Slovene,” “non-indigenous” burek being in the hands and mouths of Slovenes bothered some people, those who – to simplify it a bit – had problems with the presence of immigrants from other republics of the former Yugoslavia. From this moment on, the partnership of the burek and nationalism starts to become more intricate, to grow, to gain weight in increasingly interesting and complex ways: when the burek’s presence bothers someone, it becomes a contested object. Thus, it is very important to the burek’s semantic genesis that the burek was a visible object, an object of observation – one of the rare (food) objects of observation on Slovene streets at a time when there were no kebabs, no pizza by the slice, no hamburgers etc., that is no “western fare.” The burek thus became an object of the nationalistic gaze, it became noticed and talked about in nationalist discourse, which began to treat it as a representative of anything foreign, Balkan, or southern. The dominant meanings which defined the burek throughout the 1980s and 1990s, which we probably hear at their loudest today, were not produced in their primary, original forms by burekeaters. What was at work was a nationalist discourse that did not accept the burek as its own. In other words, it was bothered by the presence and visibility of the burek on Slovene streets, in the hands and mouths of youths and all others who occasionally ingested bureks. The nationalist discourse thus bit into the burek and the burek was no longer just food, but also or even primarily a signifier, a symbol, or a metaphor. It didn’t just fill Slovenes with calories, but also with symbols. It wasn’t just food, it was food for thought.