T he practice of ranking countries according to their inhabitants’ average weight expresses our contemporary obsession with fat and its seemingly global advance. 21st century globesity rankings differ from early modern observations of particularly portly peoples in both form and jargon. Regarding their content the difference seems less pronounced. Current epidemiology sometimes reverses prestatistical attributions, but occasionally it confirms them. Regardless, comparative approaches old and new serve the same cultural function, as I argue, because they both use corpulence abroad to address concerns and ultimately mold self-images at home.

he practice of ranking countries according to their inhabitants’ average weight expresses our contemporary obsession with fat and its seemingly global advance. 21st century globesity rankings differ from early modern observations of particularly portly peoples in both form and jargon. Regarding their content the difference seems less pronounced. Current epidemiology sometimes reverses prestatistical attributions, but occasionally it confirms them. Regardless, comparative approaches old and new serve the same cultural function, as I argue, because they both use corpulence abroad to address concerns and ultimately mold self-images at home.

Contemporary popular coverage of countries, which rank high in globesity statistics, largely depends on how their situation can be related to ours. Currently, nine of the ten countries leading most statistics are Pacific island nations. Corpulence on Samoa or on tiny Nauru serves, for example, to corroborate the thrifty gene hypothesis, still widespread in Western expert and popular scientific discourse. The chronic risk of food shortage on the isolated archipelagos had allegedly fostered a genetic disposition towards highly efficient metabolizing. Yet other world regions, whose overflowing waistlines fail to relate to our own corporeal concerns, suffer meager coverage. At least some narrative flavor is added to the Mexican story when the overflowing of “obesogenics” from its northern neighbor and supposed world leader in fatness is exposed. The traditional love of sweet and starchy foodstuffs cited to explain Kuwaiti, Qatari, or Egyptian bulges, however, is no more than an aged fragment of orientalist thinking, failing to address current Western problems and capture our attention.

Early modern observers of the world of fat would probably be surprised at our lack of interest in the flesh of Egypt. In his late 16th century works on Egyptian natural history and medicine, the Italian physician, Prospero Alpini, detailed eating, drinking, and bathing habits that he thought fattened bodies along the Nile. His observations were picked up time and again in early modern texts. The anonymous author of the 1771 Briefe eines Arztes an die Frauenzimmer, for example, reveled in accounts of female balneological, alimentary, and moisturizing indulgences resulting in full womanly figures. In a prestatistical age, girth-related distinction did not build on differences in numbers but instead assumed the form of diverging moral and aesthetic traits. However, such portraits of the opulent trans-Mediterranean other ultimately served the same cultural function as tables and graphs do today, because they shaped and sharpened Christian self-images as more moderate in habit and proportion.

With fewer pleasurable details than those offered from Egypt, frequently Europeans found corpulence just around the corner. Germans and Swiss were often considered heavy. The English joined the club of the bulkiest Europeans in the 17th century. A century earlier their North Sea neighbors, the Dutch, were regarded as a hefty people. Dutch corpulence illustrated to their 16th century contemporaries that some nations are prone to stoutness because of environmental factors. One of the foundational texts of Western medicine contains the blueprint for this idea. The Hippocratic On Airs, Waters, Places argued that because of climate conditions, including the makeup of air and soil, the Scythians, a nomadic horse people, possessed a cold and wet constitution which in turn promoted corporeal growth.

Adapted to changing medical fashions, this notion was carried into the modern era. William Cullen of the 18th century Manchester Medical School diagnosed the Dutch as either fleshy or watery, both conditions summarized under the heading of slackness. Conversely, Spaniards and Italians who inhabited hot and dry territory were commonly considered thin. The case of the Egyptians seems to counter this rationale. Instead, the Egyptians were cited to demonstrate that lifestyle choices trumped environmental conditioning. They reputedly loved their women fat urging them to gain weight. In his 1683 dissertation the physician, Karl Christian Leißner, also found peasants and Venetians guilty of worshipping and promoting generous silhouettes. Other peoples simply had a weakness for excessive consumption, which, in the German case, was said to conspire with the cold Northern climate to boost body fat.

Attaching inner-European labels, too, served to establish distinctions and elevate one’s own position. Béat Louis de Muralt reflected a widespread sentiment when he asserted, in his 1725 comparison of the English and the French, that suffocating in fat constitutes a common cause of death in England. The English physician, Edmund Gayton, self-consciously acknowledged the fattening conditions in England in 1659. Other English authors reversed the implications of their reputed plumpness and wore the derisive label as a badge of pride. Joseph Addison, for example, in a 1716 essay “On the Vanity of the French Nation,” scolded the French for mocking English bulk “as if Corpulence was a proper Subject for Satyr, or a Man of Honour could help his being fat, who eat suitable to his quality.”

While Egypt constitutes a case where contemporary globesity statistics confirm age-old stereotypes – with unsettling consequences for modern medical statistics’ claims on epistemological distinction and primacy – the English case further demonstrates that rankings, and corresponding self-images, could be reversed over time. Thomas King Chambers, a medical authority on the issue, declared corpulence a hereditary English trait in 1850 and characterized the Americans as decidedly thinner. In 1877 the neurologist, Silas Weir Mitchell, presumed that the large number of corpulent Britons must strike every American visitor as remarkable. While 19th century contemporaries continued to expect bigness at the Eastern shores of the Atlantic, their 20th century descendants had the opposite experience. The German-born physician and psychoanalyst, Hilde Bruch, retrospectively placed the origins of her interest in obesity at the moment when, coming from the UK to New York in 1934, she first encountered large numbers of corpulent children. Forged during the early 20th century, the image of the inordinately fat American survived the rise of globesity statistics and ranking, even though the US has not been leading such rankings at least since the WHO began to paint the picture of a global obesity epidemic in the 1990s. Yet the notion persists in everyday conversation and in the mass media precisely because the US serves as a point of reference and comparison for post-industrial countries in Europe and beyond.

While 21st century popular epidemiological lore in Europe continues to embrace the theme of oversize America, contemporary globesity statisticians seem determined to end the age-old transatlantic competition. The Non-Communicable Diseases Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) must have confirmed Britons’ worst fears when it decided to group countries according to both the epidemiological past and future prospects in their 2016 report on global obesity. While in all other cases this led to geographic clusters, for the Anglo-Saxon world it resulted in the unique category of “High-income English-speaking countries,” in which post-industrial Commonwealth countries across the globe, including the UK, were lumped together with the US. If such computations are to be believed, corporeally the transatlantic world converges. Even such bold mathematical moves, however, fail to end comparisons of circumference with their long traditions and their firm footing in contemporary public discourse. Instead, they simply open new areas for corporeal competition and corresponding cultural imagery.

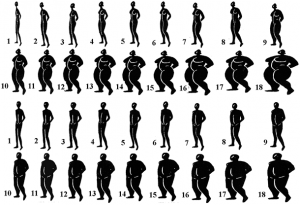

Image provided by the Wellcome Library, License: CC-BY-NC 4.0

The 1806 colored etching by Charles Williams contrasts the silhouettes of two Englishmen, Daniel Lambert (1770-1809) and Charles James Foxx (1749-1806). Already during his lifetime Lambert was commonly regarded, in England and beyond, as the heaviest man, and he frequently served as a symbol and image of British international political weight, among others, in caricature comparisons with revolutionary France.