Women at the Butcher’s

The German weekly newsreel, the Ufa-Wochenschau, opened their program on 23 November, 1962 with a sequence from a West German butcher’s shop, portraying a group of women shopping. Examining the meat at display, they all shook their heads expressing their dissatisfaction with what was available: “That’s too fat! No thanks, that’s too fat!“ they chorused, shaking their heads.

Their voices marked an ultimate turning point in the relationship between food and health in modern German history. For the first time changes in the labor market and the growth of prosperity led to worries about excess in society as a whole in the 1960s, instead of the previously known worries about scarcity. Less physical work, less need for calories, an increasing income, and first concerns about fat consumption and its relationship to cardiovascular diseases let concerns of “too much” finally outweigh those of “not enough.”

This turn, however, did not mean that Germans ate less. They ate differently. In a 4-person household, the consumption of lard had dropped by two thirds between 1950 and 1960, while the consumption of ham increased more than four times within the same period. Leaving the years of scarcity after World War II behind, taste and health replaced cheap calories as the basis of decision-making at the butcher’s—especially at the expense of pig fat. This shift yielded consequences, reaching deep into practices of animal farming and the bodies of pigs produced for consumption.

Pigs in the Lab

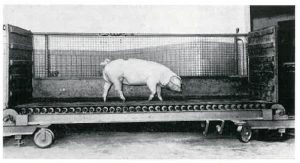

Workout experiment (treadmill), Max-Planck-Gesellschaft – Dokumentationsstelle, Max-Planck-Institut für Tierzucht und Tierernährung Mariensee/Trenthorst, Neustadt a. Rbge 1967, p. 39.

Years before Germans themselves started to run on the treadmill for fitness, pigs did. Or at least the ones in the Max-Planck-Institute for Animal Breeding and Animal Nutrition in Mariensee and Trendhorst in Lower-Saxony did. The sow in the picture on the right runs a home-made treadmill in order to feed the scientists with information about her body’s conversion of fodder into meat without becoming too fat. Thus, they no longer ought to become the fat that German women didn’t buy anymore.

Professor Max Witt, the Director of the Institute, had worked on a new ideal animal for human consumption, the so-called “German Fleischschwein,” since the early 1950s. Looking at other industrialized countries, he anticipated a change in consumption habits. The new Fleischschwein he and his colleagues designed at the MPI was to be bred “for pork instead of lard.” Its carcass offered more succulent meat than its predecessor, the Fettschwein. But how did they re-design an animal?

The answer is twofold, showing how entwined breeding and raising techniques of livestock animals were. First, Witt and his colleagues found out that the hereditary disposition of the animal determines its capacity to build meat. Starting at a certain point (different from animal to animal) the pig would no longer transform its fodder into muscles, but only into the no longer wanted fat. Strategic breeding, that is mating those animals whose bodies showed the desired features, would delay that point. In addition, breeding concentrated on transforming the pig’s body as a whole. The new Fleischschwein had a longer body, featuring one or even two ribs more. The breeding efforts in Mariensee faced, however, unexpected difficulties. The focus on gaining as much meat as possible led to deficiencies in skeleton and muscles. Too much meat weighed on bones that were not yet strong enough. The new pigs had difficulties in moving and mating. In addition, the meat of the Fleischschwein did not match consumers’ expectations: it was indeed less fat, but also of reduced keepability; it rotted faster, contained more water which led to losses while cooking, and its color was more pale than red (issues pig breeders are working on until today). In 1970, Erich Schilling, a colleague of Professor Witt at the MPI, stated: “Breeding now has clearly exceeded the biological limits of the pig’s constitution and metabolism.”

The pig’s physiological objection limited the scope of breeding potentials and made altered raising methods the second important part of the transformation into the Fleischschwein. Witt’s team made several findings that changed the way the pigs were raised: They discovered that beyond each animal’s inherited maximum limit for the growth of meat all fodder energy was automatically transformed into fat. The building of fat, in contrast, had no inherited maximum level but would continue according to the fodder offered. Regardless of hereditary dispositions, however, each pig would put on more meat than fat during its youth, as long as it was still growing. Only when fully grown, it would more likely put on fat. Finally, researchers found that the heavier the animal became, the more fodder it needed for each additional kilogram of weight. One kilogram fat contained six times as much calories than one kilogram meat and thus needed much more fodder to be built up.

Capitalism in the Stall and the Animal’s Business Economics

The animal’s business economics discovered at the MPI linked fodder, meat and money and were the reason why German pig farmers were eager to do what Professor Witt suggested. In 1961, fodder costs were counted responsible for not less than 70 percent of the overall cost of pig farming. Relative fodder costs (relative according to the pigs’ fattening process) were identified as the most important variables of farm efficiency. The better the animals’ feed conversion and the higher their maximum limit of meat growth, the better the farmer’s competitiveness and profit. That resulted in the Fleischschwein being killed as soon as it finished its most profitable phase of growth. Its weight when slaughtered was up to 50kg below the not uncommonly 150kg of the Fettschwein. The knowledge produced at the MPI allowed for an optimization of the farmers’ business administration, which was welcomed in the pigsty as well as in parliament. Politicians and agricultural planners in Bonn as well as Brussels—since 1958 agricultural policy was commonly dealt by the newborn European Economic Community—were fond of the new pigs and their business economics. The new animal and its increased productivity facilitated West Germany’s development path. It helped reducing the number of people working in agriculture while enabling the remaining farmers to earn more money with their animals. High animal productivity guaranteed a better supply of meat and even helped to export some of it, thereby improving the Federal Republic’s balance of trade. Thus, cheap meat was not only a housewife’s dream: Cheap foodstuffs were a precondition for the consumer society to develop. Cars, fridges and living room couches could only be afforded from the money left over after shopping at the butcher’s.

And the Moral of this Story…

Around 1960, the average German pig turned into the Fleischschwein because most Germans’ meat preferences changed: Lean meat was increasingly in demand, no longer thick slices of fat. Tracing the newly desired lean meat back from the butcher’s counter to the living animal, this story opens one’s eyes about the dynamics of modern foodways. Altered consumer choices shaped the animal and the way it was produced; in this case noticeably facilitated by the producers’ increased return it allowed at the same time.

The story of the German Fleischschwein shows how body ideals and food-related health concerns were pegged to historical context. The nutritional development between 1955 and 1965, together with the experience of scarcity of the decade before, shaped those values for a good deal. For concerns of “too much” to emerge, a certain degree of abundance was needed. And for the women at the butcher’s counter who no longer wanted to buy fat meat, this was most certainly a pleasant development.