SLOW FOOD is an organization that was founded in the Italian region Piedmont in 1986 by the left activist and sociologist Carlo Petrini. It has developed from a small cultural association into an international brand that combines entrepreneurial structures with a global vision of ‘better’ food. As this post will argue, its history also highlights the cultural-political contradictions of Italy’s bourgeois left.

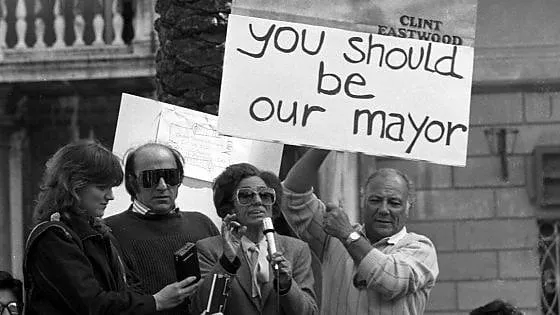

An important event that is frequently mentioned as the symbolic founding act of SLOW FOOD is the so-called “Battle of the Piazza di Spagna” on March 20, 1986, when people were rallying against the opening of Italy’s first McDonald’s restaurant at the Piazza di Spagna, the most prestigious address in Rome. Next to Petrini, protestors included Italian high society members, among them fashion designer Valentino, who had his atelier just a around the corner and feared the stench of fried food on his impalpable fabrics. With the cry of “Save Rome,” the protestors warned against the American invasion of the capital and, ironically, called for the intervention of Clint Eastwood, as the picture shows. A few weeks earlier, the actor and director had won the mayoral elections of the small town Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, and had immediately begun to crack down on several fast-food restaurants in the seaside community.

The protest on the Piazza di Spagna, however, did not go unchallenged. Simultaneously, a crowd of adolescents arrived. These young people were “paninari” (from Italian panino: “sandwich”), as the most common Italian youth culture was called, an allegedly unpolitical subculture, born “at the edge of the suburbs” and adhering to a lifestyle based on appearance and consumption. At the “Battle of the Piazza di Spagna,” they showed up to reclaim their piece of the American dream in the round and juicy form of a Big Mac.

What happened on the Piazza di Spagna in March 1986 was a political conflict of cultures, a collision of Weltanschauung, where the bourgeois class armed with a decent amount of anti-Americanism fought for what they framed as traditional values of Italian cuisine. The paninari, on the other side, were a new generation of Italians who were literally fed up with the arrogant display of bourgeois values. Interestingly, at the preliminary end of this conflict, the restaurant remained open.

Interpretative Power Over Food and Culture – the Manifesto

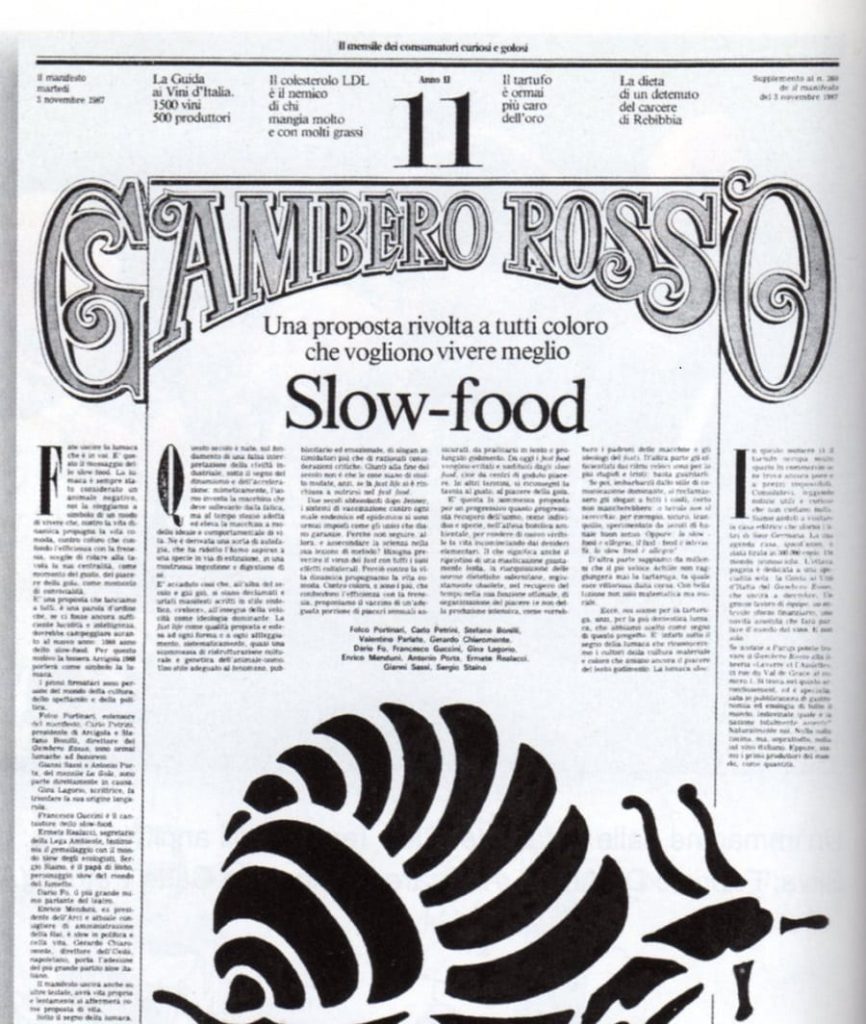

The Battle of the Piazza di Spagna is recalled in the circle of SLOW FOOD adherents until today when remembering the association’s foundation of 1986 by Carlo Petrini in Bra. It was the “avant-garde’s riposte” to the “tediousness of fast-food,” the prominently placed manifesto of SLOW FOOD stated. As Antonalla De Santis argues, the manifesto was a “collation of utopian intentions, [a] list of NOs to the ’80s world – a world whose supreme value was velocity countered in the document by the importance of slowing down.”

Despite its political reminescences, the manifesto was not an abstract program based on socio-economic and political ideals. SLOW FOOD went on stage as an artistic intervention, carrying its poetic appeal in a visionary style. Notwithstanding the use of a “leftist” form of expression in language and visual aspects, SLOW FOOD did not intend to change society as a whole, but only the lifestyle of those who could afford it.

The manifesto stated: “Born and nurtured under the sign of Industrialization, this century first invented the machine and then modelled its lifestyle after it. Speed became our shackles. We fell prey to the same virus: ‘the fast life’ that fractures our customs and assails us even in our own homes, forcing us to ingest ‘fast-food.'” Starting from a large-scale critique of modernity, of alienating living conditions and a general cultural pessimism, the concept of SLOW FOOD offered a rather modest program of a cosy retreat into the private sphere: “Against those – or, rather, the vast majority – who confuse efficiency with frenzy, we propose the vaccine of an adequate portion of sensual gourmandise pleasures, to be taken with slow and prolonged enjoyment,” the manifesto claimed, or, more pointedly: “Slow-food is cheerfulness, fast-food is hysteria.“

Today SLOW FOOD is an international movement headquartered in Bra, Piedmont, Italy, and organized around small, local chapters. SLOW FOOD’s mission, according to their website, is

“defined by three interconnected principles: good, clean and fair.

GOOD: high quality, tasty, and healthy food.

CLEAN: production that does not harm the environment.

FAIR: accessible prices for consumers and fair conditions and pay for producers.”

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the SLOW FOOD movement counted sixty-five thousand members in forty-five countries on five continents – however, 75 % of the members live in Europe and another 17 % in North America. The group’s activities include public education forums, such as guided taste workshops, school programs, and conventions. Additionally, it offers publications, such as guides to wine, cheese, restaurants, food and wine cultures, and tourism.

Over the years, the initiative, once critically deemed as a self-serving tool of the so-called “caviar-left,” developed into a fully-fledged global multiplayer that organizes trade-fairs, holds an economic wing called Eataly providing franchise restaurants internationally, helps to coordinate a catholic grassroots organization and various neighbourhood help and education programs, and runs a private university, financed by tuition fees.

The organization’s success started with creating a nostalgic idea of authentic Italian food culture and conviviality which it developed, in collaboration with the National agency of Italian Tourism, into an internationally recognisable brand.

A Global Enterprise With Neocolonial Tones

At the same time, this idea of Italian conviviality and authenticity forms a distinguishing feature within the Italian bourgeoisie, associated with a particular linguistic and journalistic culture of the Italian left. Thus, the SLOW FOOD idea is difficult to condense into a uniform figuration. It oscillates between the affirmation of a progressive and leftist distinction and a tightly run business enterprise, and again a worldwide anti-capitalist network that relies on decentralised, localised structures and charity projects in the developing world. All in all, these characteristics form a very contradictory conglomerate.

Some of SLOW FOOD’s activities are not free from neocolonial overtones. For example, in 2014, a march of SLOW FOOD representatives with banners saying “We are all Africans” accompanied the launch of the project 10.000 Gardens for Africa, campaigning for the creation of “good, clean and fair” gardens in Africa. Yet, those people rallying for Africa were NOT Africans. This action leaves an odd impression, even more when juxtaposed with Italy’s colonial history in Africa. The initiators of the project enjoyed all the privileges of former colonizers. This being said, I am aware that these measures do not represent the opinion of the whole Italian population, let alone the proponents of the 10.000 Gardens for Africa-project. However, the campaigns leave the impression that building up “traditional” structures in Africa was intended not predominantly to help the population but to fill certain expectations of authenticity from European donors.

SLOW FOOD founder Petrini’s recent activities, including the development of solid business structures and a franchise system borrowing the concept of SLOW FOOD, shows the long-ago departure from leftist ideas, if there were any. Instead, the commitment to philanthropy and sustainability of organizations affiliated to SLOW FOOD – like the Ark of Taste, a project to save endangered plant species in a seed bank – echoes neocolonial tones when it claims to safeguard foods and cooking techniques endangered by “industrialization, genetic erosion, changing consumption patterns, climate change, the abandonment of rural areas, migration, and conflict.” This negates the possibility of and the right to modernization of whole sectors of the Global South for the sake of an “organic” and “authentic” lifestyle of European and American consumers. Thus, the rhetoric of change in the idea of revolution reveals, in the end, a far less progressive program. Instead of radically changing production and market conditions, SLOW FOOD reproduces the old ones, leaving untouched or even aggravating the deep inequalities between North and South.

In the context of SLOW FOOD, notions of eating right can exert a moral pressure while being inherently ambiguous. Equating eating right with being a morally upright person justifies, in a certain sense, individual high-end consumerism and relegates questions of global justice to the margins. Of course, the vision of a better world and the proclaimed goals of SLOW FOOD of “good, clean and fair” – aiming at producing high-quality food while paying attention to the preservation of regional biodiversity and careful use of resources – make a fundamental critique of the idea difficult. Nevertheless, at the end of the value chain, it is once again the high-income groups of the Global North that are the beneficiaries.

This text would have been much poorer without the lengthy and engaged discussions with (strictly alphabetically): Margherita d’Ayala Valva, Francesca Fabbri, Louise Sarica and Sandro Schwaderer.