In both contemporary medical and cultural discourse, a relationship between fatness and excess is often perceived to be self-evident. Being “overweight” is consistently connected to “overeating” and “overindulgence,” with the implication that if one simply ate less and practiced greater self-control they would lose weight and would stop being fat. Fat bodies may thus be perceived as transgressive since they are thought to transgress the norms of consumption.

In the early modern period, however, the connection between excess and fat was not as straight-forward. While ideas about excess and excessive behavior permeated German-speaking society in the sixteenth century, excess was not always understood to result in fatness. Contemporary criticism of gluttony and drunkenness commented on the effects of such vices on the body, yet this commentary typically focused on the overflowing of the body’s boundaries as a result of excessive consumption. What was consumed in excess was shown to spill out of the body in the form of vomit, sweat, urine and excrement. The excessive body could thus be imagined as a kind of vessel in this period, just as Lutheran theologian Eberhard Weydensee (1486-1547) stated that, with drink, people ”pour more and more wine and beer in at the top and when it is full, they let it run out the bottom, yes, sometimes it climbs out of the top.”

This image of the excessive body as a vessel did not rely on an association between excess and fatness. Yet this is not to say that a connection between excessive consumption and fat bodies did not exist at all in this period. In this blog post I explore the complex relationship between body size and consumption in early modern Germany, showing that understandings of fatness and excess were closely, but not exclusively, connected.

The Fat Belly and the Schlauch

A useful starting point to uncover the connection between fatness and excess is the Schlauch, a kind of drinking vessel which was frequently used to present excessive bodies as bloated and expansive. In Hans Weiditz’s print Winebag and Wheelbarrow from the 1520s, the drunkard’s body is shown to be an overflowing vessel, with vomit spurting from the man’s mouth. As well as overflowing, however, in this case the excessive body is clearly related to an image of fatness. The print presents the “Winebag” (Weinschlauch) with a belly so distended that he has to support it in a wheelbarrow.

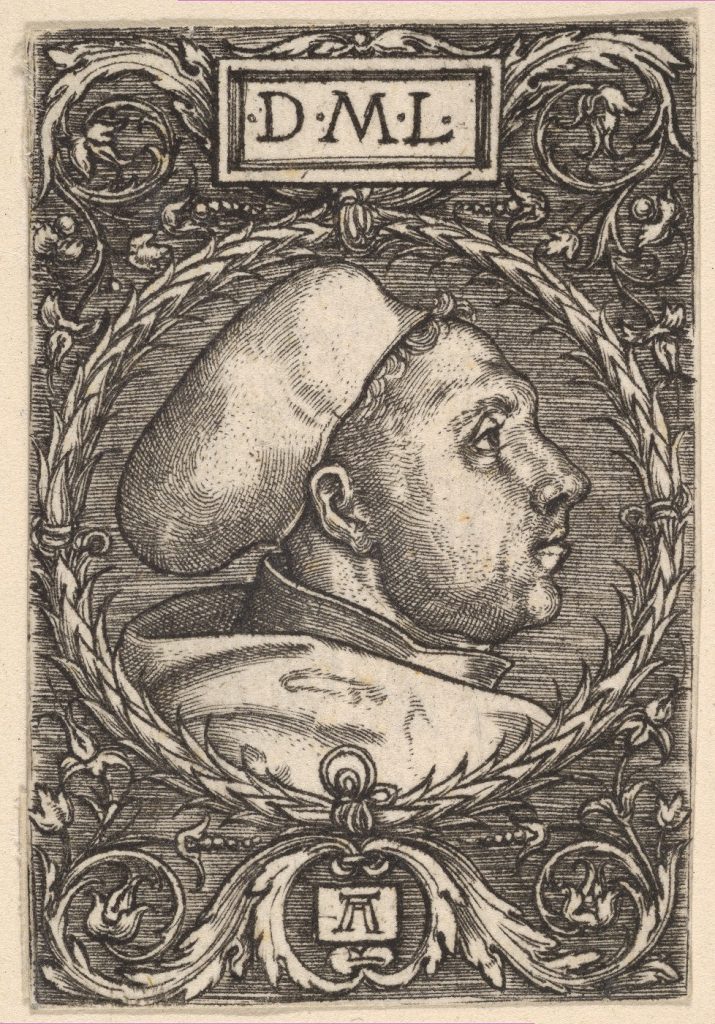

Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons.

This image of expansion is connected to the man’s description of himself (in the accompanying text) as a “Schlauch.” Excessive drinkers were often associated with this type of drinking vessel which was a kind of pouch or bag into which drink could be poured. In the poem accompanying a woodcut by Erhard Schön, the Peasant Wedding Celebration from 1527, it is stated that a wedding guest called “Brave-Belly” has a “wide Schlauch, he looks like a big pot-belly which he likes to fill up considerably … until it all runs out of him.” As in Weiditz’s image, here the Schlauch is associated with both overflowing excess and a fat belly.

Being described as a Schlauch in these moralizing and humorous works,the excessive body was shown both to flow out of its boundaries and to stretch them, and the material nature of such containers enabled this comparison. Often being made of animal hide, the Schlauch could be equated to the human body, itself encased in skin, and it would also have been relatively malleable, with the capacity to expand and swell when filled. The comparison of the excessive body with the Schlauch thus gives us an insight into how excess could be understood in relation to body size in this period. It suggests that the criticism of excessive consumption was not only concerned with the crossing of bodily boundaries, but also with the swelling of such bodies which expanded through the volume of food and drink being poured into them until they no longer resembled their original, or “natural,” proportions. It is to this concept of “natural” body size that we now turn.

“Natural” and “Unnatural” Fat

The criticism of self-imposed bodily expansion was echoed in early modern medical texts. A distinction that arises frequently in works which discuss fat bodies, is the difference between one who is “naturally” fat and one who was born with a “middling-sized” body yet has become fat through excessive consumption. The physician and pharmacist Christoph Wirsung (1500-1571) spoke of those who “from nature are of middling size, but from delicious foods and many sweet and fat dishes, constantly eating meat and frequently drinking, and in sum living in lust and pleasure” fatten their bodies. Wirsung suggests that these people deserve greater condemnation than those who are fat “naturally” because they have brought the “sufferings” of the fat body on themselves by living excessively.

The Tirolean physician and militant Catholic, Hippolytus Guarinonious (1571-1654) was more aggressive in his condemnation of those who made their naturally slim bodies fat. He wrote, “when one doubles the size and weight of the unchaste flesh, with such skill [as through excessive consumption] what can one be other than a double brute and a purely conceited unnecessary excrement and earthly burden? This adds to the difference [between such people and] those who are born fat and large of body.”

The understanding of a “naturally” fat body and an “unnaturally” fat body is a crucial point in approaching the relationship between fatness and excess in this period. The criticism of excess in relation to fatness was particularly aimed at bodies which had become fat “unnaturally.” Such bodies had expanded beyond their “natural” size, which was determined by the body’s complexion and balance of the humors, and ultimately by divine providence. These bodies departed from the form bestowed upon them by God, instead becoming fat and bloated through excessive consumption. According to this understanding, “excess” was therefore the consumption of a greater amount of food and drink than was needed to sustain one’s “natural,” and intended, body size. “Naturally” large bodies could, therefore, be more acceptable to early modern moralizers than those that were “unnaturally” large, since they were not the result of gluttony and drunkenness but of God’s own creation. This indicates that fat bodies were not always understood to be transgressive in this period, as this was primarily the case only when such fatness was perceived to result from excessive consumption.

Lutheran Moderation

This understanding helps to explain how some fat bodies could be both praised and idealized in this period despite the simultaneous condemnation of excess on both medical and spiritual grounds. Historian Lyndal Roper has shown, for instance, that Martin Luther’s large body was viewed positively by Lutherans as it represented his rejection of monasticism, including the practices of asceticism and celibacy. Yet Luther and his followers still needed to reconcile his large size with their spiritual teachings against gluttony. A key factor which allowed them to do this was the Lutheran understanding of moderation, which meant eating and drinking to sustain the “natural” form of the body. Luther stated that “everyone must look to themselves and how they feel, because we are not all the same and so there can be no common rule” when it comes to eating and drinking. Writing of the Elector of Saxony, Luther stated “our elector, who is quite a robust man, can stand a great deal of drinking. What he needs to satisfy himself is enough to make his neighbor drunk for he is a man with a very strong body.” To make allowance for his elector’s excessive drinking, Luther thus presented it as necessary rather than immoderate because his body required a “great deal of drinking” to be satisfied. The eating of a large amount of food by someone with a large body might similarly be justified, as they would need more food to sustain their “naturally” large size.

When approaching excessive bodies in early modern Germany from cultural, medical and religious perspectives, therefore, the contemporary distinction between a “naturally” and “unnaturally” fat body is crucial. Of course, what constituted a “natural” and “unnatural” body could be subjective and complicated. Yet by acknowledging this distinction we recognize that the essential transgression of excess in relation to fatness in this period was in the expansion of the body beyond its given form through excessive eating and drinking. The idea of self-responsibility for “unnatural” fat presents a kind of early modern “fat shaming” by which greater moral opprobrium was apportioned to those who were perceived to have brought the burden of fatness on themselves through their own lack of self-control. Yet the concept of natural body size in turn indicates an early awareness that every body is different, that we cannot all achieve the same bodily ideals and that some people are simply fatter than others, without this being a reflection of their moral character. This message connects to those of activists seeking an end to present-day fat stigma and offers a welcome challenge to any simple association between fatness and excess.

Telkom University says:

Cultural Perceptions: How was fatness viewed in early modern German society, and what were the cultural attitudes towards body image during this period?