I watch a video of professional marathon runner Mirna Valerio. Juxtaposed with the footage of her fat black body running through the woods, she reads—in a static, calm, level voice—an email that was sent to her: “You are a liar and a fraud. You are not a runner. I have seen your few videos where you actually pretend to run. What a joke! You are moving no faster than I can walk.” I watch Valerio’s body zig and zag in between trees. The camera lens lingers on her thick thighs as they land on the damp earth with thuds. I watch the flab on her arms and tummy jiggle, listen in for her deep breaths. She is not fast, but steady. Not effortless, but labored and intentional: “A true professional runner is not overweight, which you are. A person who runs marathons for a living is not overweight, which you are. Fuck you. You want to further fat acceptance and people killing themselves in your perverse idea of beauty. Fuck you.”

Even as a non-black, fat femme of color who is no stranger to the public violences enacted upon fat people of color—ranging in severity from snide comments to physical harassment to medical negligence—I am taken aback by the force of rage in this anonymous letter. Why does a fat, black woman merely living and moving through space conjure such intense feelings for a complete stranger? I take this video as a visceral example of what I call thin-rage—of an explosion of feeling that is not exclusive to the domain of thin people, but rather, a psycho-affective investment in maintaining a social hierarchy of bodies through targeting racial and diverse bodies. Thin-rage is the production of outrage, grown through the ideas that “health” is the only pathway to public good, and therefore, justification for the violent anger towards racialized fat. Thin-rage maps a power moving in one direction: towards futurity, progress, and perfection where one must earn the right to dignity.

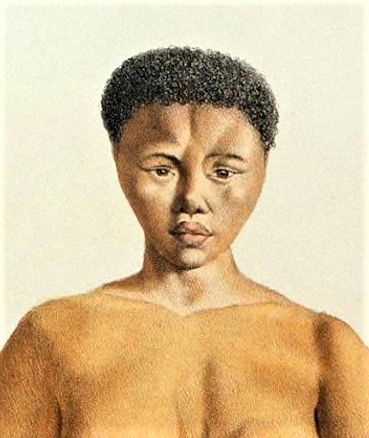

As Fat Studies scholars have argued, thinness is not assumed as a natural state of being, but rather, as an ideal we move toward by conditioning the body, regulating consumption, and working to tuck and tone to keep a shape that is desirable. Thinness, then, becomes an ethical promise, a gendered and racialized moral exercise upon which to act out the good citizen, good consumer, and good woman by, literally, fitting in. As I study Valerio in this video, thin-rage hovers in the atmosphere, attempting to render her body as wrong by all accounts. Thin-rage punctures—the scalding words of the anonymous letter writer brings the beliefs of western modernity into sharp relief: that a subject unable to master their body is inhuman, that blackness and fatness is a double-mark. “Perverse idea of beauty” conjures the nostalgic colonial rhetoric of the Hottentot Venus, where European medical practitioners, eugenicists, and anthropologists atomized the bodily differences of Saartjie Baartman’s flesh into the criminal adipose tissue that haunts the contemporary War of Ob*sity. The stickiness of race and fat and perversion have seen many permutations over the years, but consistently tell the story of how racialized bodies fail to progress beyond the savage to the civilized.

At the same time, what is layered over the pricking of thin-rage is the possibility of attuning to different readings of the black, fat femme. Listening to Valerio’s voice and watching the movement of her offers us an opportunity to see a different kind of fullness. Andrea Shaw argues in the Embodiment of Disobedience that “throughout the African Diaspora the fat black woman’s body operates as a polyvalent retaliatory agent that responds to the impact of colonization […] Her size further illustrates her chosen disobedience since its corpulence may also be read as sufficiency and therefore a lack of desire to ingest the alien ideologies that have already rendered her beyond the periphery of the dominant culture” (9). Through Shaw’s archive of African diasporic and postcolonial literatures, she reckons with the disobedience of black women’s bodies across two vectors: the first being the ways in which blackness is conscripted in a white, colonial world as non-human and inferior, and the second as her bodies inability to tame itself from fatness, or, going in the wrong direction.

In this refusal or inability to fit within normative frameworks of embodiment, the fat, black, female figure—as cultural productive in the visual and literary—offers different ways to read resistance and power. Shaw writes: “The fat black woman’s body poses a dual challenge to the colonially inspired dominant aesthetic norms that are instituted as a political mechanism for control; these norms symbolize the hegemonic force from which they arise. Her fat black body resists both imperatives of whiteness and slenderness as an ideal state of embodiment” (11). Turning back to the video, I look to Valerio. The horizon of her body is naturally uneven. Visually and affectively, she splits through timelines. The life that she lives, a life of motion and doing, is violently interrupted by an insistence on bodily regulation, perfunctory health and aesthetics, visceral anger and disgust. It is the disembodied voice of rage which seeks to render her moving body as something inert, static, and going nowhere.

Though I hesitate to say that this video is one that encapsulates body liberation, as it is so clearly the product of a capitalist economy seeking to sell their wares to a widening consumer base, I am struck by how the veneer of public health and good performed by the anonymous letter writer cracks apart as they attempt to render a hierarchy of flesh legible by disavowing Valerio’s athleticism. It is apparent that such comments are not about public welfare, but instead about maintaining the status quo of which bodies can thrive. When we learn to read this tension—between a fat, black life in motion and doing and the thin-rage that antagonizes violence against her very being—the threads of power, whiteness, and coloniality begin to surface and unwind, untether and unmoor us towards new horizons of possibility.

A German translation of this text will be published in the upcoming publication Fat Studies: Ein Glossar (transcript, 2022).

Margaret Bartley says:

Thank You

Terri L Weitze says:

This is not only contains important information, the writing is beautiful and powerful.

Melissa Nievera-Lozano says:

I love the way you write. Thank you for this.