Like today, in the 1940s and 50s plenty of people in Appalachia—a mountainous region in the eastern United States—enjoyed eating ramps, a pungent wild onion that reaches its prime in April. But that consumption meant something very different in 1950 than it does in 2023. In the mid-twentieth century, foraging for the first wild greens of the season was a sensible, healthy thing to do, even if it meant you smelled like ramps for several days. Yet that lingering scent indicated a lower-class status, since it implied an inability to access and purchase fresh vegetables. Conversely, in 2023, eating ramps signals insider foodie status: they are the height of trendy eating for many Americans, Appalachian or not. This April, University of Georgia Press will release my second book, Appalachia on the Table: Representing Mountain Food and People. In it, I explore where Appalachian food scripts like this one came from and the ways in which they continue to evolve.

Constructing a Mountain Food Narrative

Most scholars agree that the concept of Appalachia as a distinctly different region from the rest of the United States began in the years after Reconstruction, though new scholarship like Michael Martin’s Appalachian Pastoral challenges that timeframe by arguing that such ideas occurred earlier. While my book considers some authors publishing before the American Civil War, most of the descriptions I discuss in my chapter on Local Color fiction and travel narratives are published in the late 1800s and early 1900s. When I began researching that chapter, I felt certain these publications would be rife with descriptions of heathen mountaineers with no culinary knowhow. I had already noticed the word “coarse” appeared frequently to describe mountain food. In a culinary sense, if food was coarse, that meant it was rough, difficult to digest, and/or not properly prepared. Likewise, I noticed the word was also used to describe mountain people. In that context, coarse meant uncivilized, unsophisticated, and/or uncouth. When combined, the implicit reasoning behind these descriptions suggested that coarse people prepared and consumed coarse foods, all of which fed into damaging stereotypes about incestuous, feuding, moonshine-making, illiterate hillbillies that were gaining traction in the late eighteen-hundreds and early nineteen-hundreds. Scholars like Henry Shapiro have written much about the effect such Local Color literature and travel narratives had on national perceptions of mountain people. These genres juxtaposed lush, beautiful landscapes with degenerate people, emphasizing heavy regional dialect, slow wits, and general backwardness. Such exaggerated renderings meant to entertain also invited readers to conflate fiction and fact. In other words, the fictional worlds these writers depicted, as well as the theoretically “true” travel narratives published in major outlets like Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, and Lippincott’s, became an imagined reality for readers across America who had never been to Appalachia. An important part of that constructed narrative was that both the people and the food that they consumed were inferior.

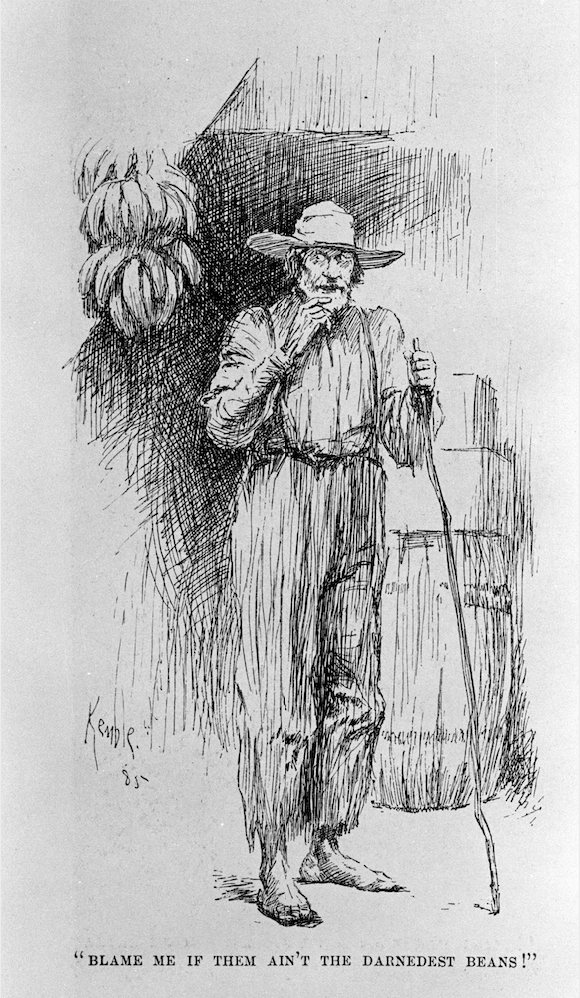

In 1886, for example, Local Color writer James Lane Allen published “Through the Cumberland Gap on Horseback” in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. The story was a commissioned piece of travel writing and intended to be read as “true.” In it, Allen chronicles his journey to Burnside, Kentucky, which he deems a “primitive society.” Allen was a Kentuckian himself, but he was from the Bluegrass region, the western part of the state he and others at the time—and some would argue today—saw as socially superior to the Appalachian region of eastern Kentucky. Allen describes the area’s recent railway and the fruit stand an entrepreneur opened thanks to newly accessible imported produce. One might think Allen would note that such a quick adoption of previously unfamiliar goods signaled modernity, connection to the outside world, and an openness to change. Instead, he describes a “native mountaineer” who sees the bananas on display and exclaims, “Blame me if them ain’t the darnedest beans I ever seen!” In this context, the mistaken mountain man is portrayed as a dim-witted buffoon who has never seen a banana; he becomes an object of ridicule, one readers are meant to find humorous. As I explain in my book, given the difficulty of transporting bananas and the country’s developing rail system at this point in history, it’s remarkable that Burnside, Kentucky has bananas at all. The man’s reaction seems perfectly reasonable. It could also be, as food writer Ronni Lundy pointed out to me, that the man was revealing Allen as the fool. Knowing Allen was looking for ridiculous stereotypes, perhaps the mountain man gave him just what he was seeking.

Deconstructing that Narrative

Examples like this one abound, and I write about them for pages. But I was also relieved to realize that once I got past the mountaineer stereotypes that characterize that era and still linger today, other writers were writing more nuanced portrayals of mountain cuisine and people. Rebecca Harding Davis, for example, provides a counternarrative worth exploring in several of her works. In her 1875 short story, “The Yares of Black Mountain,” a tourist named Nesbitt disembarks from a train in Old Fort, North Carolina and wryly remarks, “Civilization stops here, it appears.” He seeks food at a nearby restaurant, only to later warn one of his traveling companions, “You would not have wanted to taste food for a month if you had seen the fat pork and cornbread they are shoveling down with iron forks.” But unlike so many of the other similar examples I discuss, in this story, someone talks back. A woman named Miss Cook retorts, “It’s absurd, the row American men make about their eating away from home. They want Delmonico’s table set at every railway station.” In her estimation at least, the problem here lies not with the food, but with Nesbitt. Davis is not alone in these portrayals: while the cringe-inducing narrative I had expected to find was there, it was also a more complex story, one complete with high-end resorts, fine dining hotel menus, and spas touting the wonders of mineral waters.

A Word of Caution

Fast forward to 2023, and many of the foods associated with uncivilized hillbillies at the turn of the twentieth century are now considered desirable. There are many examples, but ramps and sorghum molasses demonstrate perhaps the most obvious shifts in culinary capital. Each of these were seen as markers of poverty earlier in the twentieth century, whereas now they are highly sought after, expensive ingredients served in award-winning restaurants. One such restaurant, Sean Brock’s Audrey in Nashville, Tennessee, features Appalachian food and is “inspired by his Appalachian roots,” according to the restaurant web site. The dishes served there are far from coarse.

To be clear, it’s marvelous that Appalachian food is finally getting its due recognition. It deserves a seat at the fine dining table. Considered together, beyond what I was able to summarize here, the authors I write about remind us that we don’t have to subscribe to “either or” binaries: whether served in an expensive restaurant, enjoyed in someone’s home, or purchased at a convenience store, mountain food nourishes its consumers and should be celebrated. That said, the authors I consider also remind us that venerating Appalachian food does not automatically venerate public perceptions of Appalachian people. There’s still more work left to do.