Fat bodies are not en vogue. In current advertisements, films, books, magazines, etc. we hardly find fat children’s bodies at all or depicted in a positive way. In her recentbook Fa(t)shonista, the German fat activist and feminist Magda Albrecht describes her childhood and her weight as a permanent occasion to comment on. The ideology of childhood seems to be one of lightness, friendship, joy, and normative bodies. Fat children or even fat heroines remain almost invisible, they are ”missing bodies” in a discourse in which certain bodies are of higher value than others, as Monica J. Casper and Lisa Jean Moore pointed out. Moreover, when fat children are depicted, they are often shown without heads or from the back. Psychotherapist and cultural worker Charlotte Cooper has coined the term ”headless fatties” for this common visualization that, although often masked as a gesture of politeness and respect, deindividualizes fat people by reducing them to their bodies. In their concept of an “ocular ethic,” Casper and Moore demand an “ethical responsibility” to make the act of seeing itself visible. Therefore I am keen to learn how kid’s fatness is seen and shown in children’s books and what the power of such images is. This implies not only dealing with the visible, but also with the invisible, with that what is left outside the frame.

Round and Round the Fat Girl Must Be

Picture books have an educational impetus and try to develop playfully an awareness of a specific problem in children’s lives such as the divorce of parents, death, or—in our case—fat. Looking at picture books we notice that rather than being represented merely as a momentary condition in the kid’s development or a simple matter of fact, living as a fat child is framed as a problem.

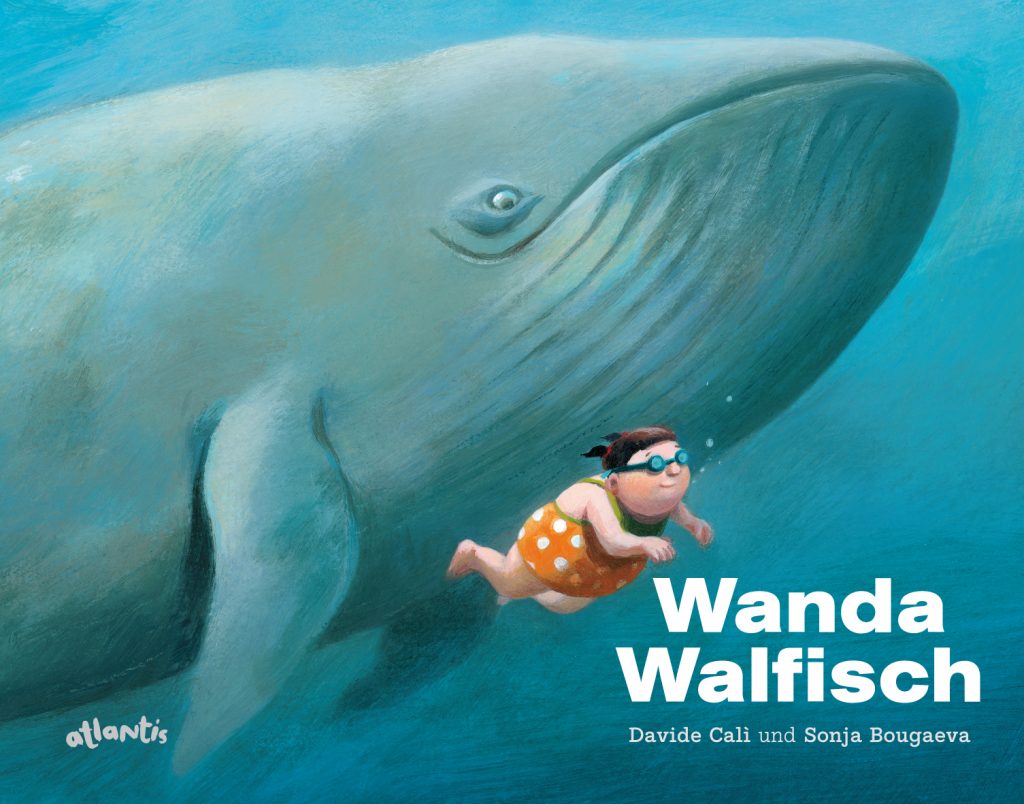

If we come to speak about children’s picture books and the depiction of fat kids, you will immediately find Wanda Walfisch (“Wanda the Whale”), originally published in French. We hardly find any German books portraying a fat main character or fat characters at all, and former fat TV children figures like Maya the Bee, Pumuckl, or Bob the Builder have lately been remodeled and lost weight.

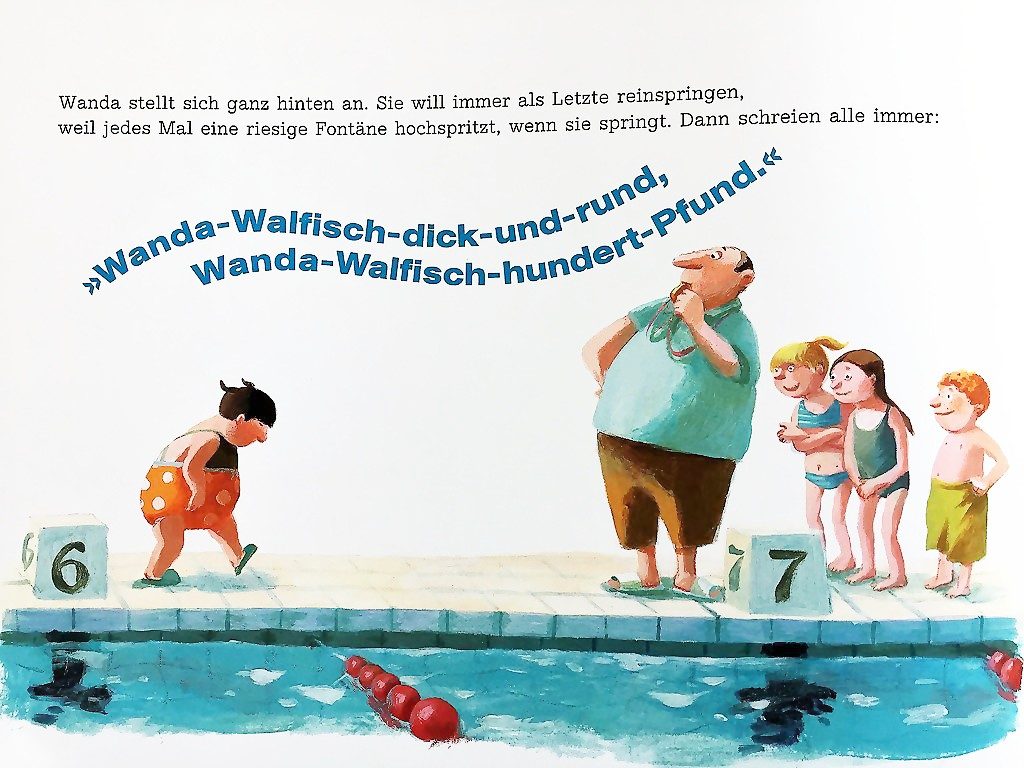

Wanda is an exception. Wanda is a schoolgirl who hates the swimming class because of the mean chorus of ”Wanda-Walfisch-fat-and-round, Wanda-Walfisch-100-pounds” that the other girls are singing while they watch the ”big waves” Wanda produces when jumping into the pool. Her teacher, though, helps her to work on her empowerment, and she imagines herself as a rocket, a statue, and finally as a whale. Imagining herself as a whale helps Wanda to learn to love swimming.

Wanda’s story is about her self-image as being fat and the internalization of her fellow classmates’ fatphobia. Her teacher helps her to stop ”doing fat,” that is to let go of behavior or thinking that signifies how a fat girl must impersonate stereotypical fatness—a concept developed by Jeannine A. Gailey in The Hyper(in)visible Fat Woman.

Literally, Wanda Walfisch is a story from doing to undoing fat. The discomfort produced in this book is that it works with a certain visual mechanism: the common association of a whale and a woman’s or girl’s body. Although well meaning, this produces and validates a hypertrophysation of Wanda’s body to one which does not fit social and cultural norms. Furthermore, the book supports the stereotypical idea that everything which is linked to the girl’s body must be round: There are a lot of visual analogies, like polka dots on the swimsuit, planets, bubbles, Wanda’s belly, face and goggles, but no other fat girls. There are other fat people such as the swimming teacher, male class mates and—probably—other older female teachers, but no one in Wanda’s peer group. Wanda is the exception who has to learn to cope with her fat-girl body alone. And although Wanda succeeds in overcoming her fear to swim in public, visually the book naturalizes an alikeness of fat girls and whales, a corporeal alikeness of humans and animals.

Another children’s picture book with a fat girl character is Jelena fliegt (“Jelena is flying”, extract here). The story introduces Jelena as ”too fat. Too Big. And too stupid.” She has no friends and lives with her parents on a fun fair. Her mother runs a gun-shooting stall, her father a rollercoaster. Jelena does not fit anywhere, neither in her clothes nor into school desks or carousels. Only at the test-your-strength-machine she is stronger than the ”strongest man,” and one day she wins the main prize—all the balloons. The owner ties the balloons around Jelena’s body and they carry her away into the sky. As she notices her worried parents she lets the balloons go and returns to them. Throughout this book, Jelena is presented as alone, nearly without emotions, and markedly passive. Although she is the heroine of the book, she is hard to identify with.

If Wanda tells a story from doing to undoing fat, Jelena establishes a close interlinking between a fat girl and a monster: She is shown as ”too much” in any respect—too big, too stupid, even her only ability—her strength—is a form of ”too” strong for a kid of her age. Monsters—as in horror movies—are strange hybrid beings, often effeminate, who are simultaneously reinforcing and threatening social and cultural norms. This monsterization of Jelena is underlined by the fact that she lives on a fun fair where fat ladies belong to the setting of former freak shows and which is itself a heterotopian space with special rules, an off-space in terms of Michel Foucault. Jelena is flying is highly ambivalent and leaves the reader with a strange unease.

Wanted: Fat Children’s Heroines

Although Wanda and Jelena are the heroines of the books, their visual representation of being different strengthens the gendered normativity of slim bodies. On the narrative and the visual level, Jelena is an example of active othering, the figurine is fully reduced to her monsterized body—the books protagonist is more a warning example than a heroine. In Wanda, the message of the book is more subtle: The kids learn how to disengage from doing fat by designing their own social and corporeal imagination to overcome all obstacles. This lesson in self-responsibility carries empowering aspects but together with the imagery that links the fat girls body only to round forms and big animals it does not support a notion of a variety of body types. This shows once again how complex and important it is to critically engage with social and cultural production processes like fat shaming to overcome discrimination, exclusion, naturalization, and normative thinking. The permanent reiteration of fatphobic imagery on the long run strengthens a discourse of visual hate speech. The deconstruction of fat shaming is a political issue and fat children’s heroines are still ”missing bodies.”