In recent years, body, health, morality and the neoliberal capitalist economy have become caught up with each other in a major way in both the public discourse and public policies concerning fatness. Against the backdrop of the dominant neoliberal rationale, the fat body has been ranked as an “expensive” body, but not just that; the fat body is constructed as a kind of “anti-neoliberal” body that is unproductive, ineffective, and unprofitable. Thus, fatness, health, and the economy are bound together materially, symbolically, and morally. This is particularly visible in the so called obesity epidemic discourse that has dominated public discussion of fatness over the past fifteen years.

In the spring of 2010, an unusual weight loss campaign ran in Finland which illustrates how fatness is portrayed as wasteful, excessive, unproductive, immoral, and expensive, and how the global economic discourse is woven into this portrayal. An anonymous sponsor had donated 10 million euros for a weight loss campaign that was named provocatively as “Läskillä lukutaitoa,” in English “Literacy in Fat.” The idea of the campaign was simple; people were encouraged to take part in a nationwide weight loss campaign and try to lose as much weight or “flab” as possible in a period of three months. For every kilogram in weight lost, the sponsor would donate 15 euros for teacher education in Nepal. The logic of the campaign was to “buy” the excess fat and donate it in the form of money to benefit children in the Third World.

The sponsor had managed to persuade an authoritative group of institutions to back the campaign. The National Institute for Health and Welfare, the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, and the Evangelical Lutheran Church—the state church in Finland—were listed as co-organizers. Having these institutions involved gave credibility to the campaign and suggested that its approach to fatness, fat people, weight loss, and health promotion was approved by the highest authorities in their respective fields. This is interesting for recommending the public to go on a crash diet goes against everything that medical experts, among them the National Institute for Health and Welfare itself, usually advise. However, this is in line with the obesity epidemic rhetoric and the weight-centric understanding of health, which sees any weight loss as good.

Thus, it is obvious that the so-called obesity epidemic provided the inspiration and politics behind the “Literacy in Fat” campaign. The obesity epidemic discourse builds on a combination of healthism and neoliberal thought, and it has represented fatness as the number one enemy and threat to societies and the economy in particular. Accordingly, in the campaign, fat phobia or anti-fat sentiment is camouflaged as a health concern. The use of the derogative Finnish term “läski” that is commonly used to abuse fat people in the title of the campaign already identified the campaign as anti-fat and driven by stigma. The term refers to animal fat and pig fat in particular. The moral judgment, however, is not just implicit in the title of the campaign. In the media coverage of the campaign, fat was construed as a sign of greed, selfishness, and over-consumption, thereby drawing on an established stereotype of fat people as hedonists with a weak will and lacking in efficiency and productivity. Furthermore, contrasting First World abundance and Third World deprivation reflects a simplistic view of both fat people and global capitalism. The campaign seems to suggest that the unfair first world surplus and excess that is embodied in people’s fat can be literally exchanged for money so that deprived Third World children receive a better education.

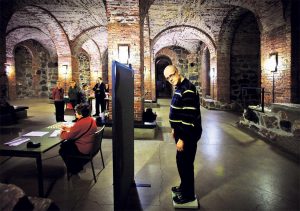

Weighing took place in churches at the beginning and the end of the campaign, as here accounted for Helsinki by the evangelical newspaper “Kirkko ja Kaupunki” (The Church and the City).

It was the sponsor’s wish that participants in the campaign should be weighed in the beginning and the end of the campaign in a church or a local parish building. An assumed gluttonous relationship with food persists as a popular explanation for people’s fatness. Eating and especially enjoying food is often talked about in terms of sin. In contrast, dieting and abstaining from eating are seen as virtuous and morally commendable. In this light, the choice of location for weighing fat (sinful) people seems deliberate. The weighing bears more than a similarity to Catholic confession rituals: the fat person comes to church to be weighed at the start of the three month period and to confess the sin of being fat, repentance follows, after which comes the second weighing and absolution of the fat person’s sins.

In “The History of Sexuality,” Michel Foucault has written about the role of confession in becoming a self-disciplined subject; and indeed the moral judgment inherent in reporting one’s weight is woven into this campaign. However, fat can be given an exchange value. If fat is exchanged for money, which will then be used to bring knowledge and better future to undereducated Third world children, it seems that fat can miraculously be transformed into an agent for productivity and morality. It appears as if the participants who are losing their fat are somehow ‘nourishing’ those children. Thus, by giving fat a monetary value the campaign promotes thinking about fat in neoliberal capitalist terms. The commodification of the human body has a long history; bodies and various parts of them have been bought, sold, and exploited in many ways. What takes place here is the commodification of fat, and it is commodified through negation. Fat is valuable only when it is assumed to be disappearing. The undesirability of fat is the basis for a myriad of plans, programs, and products that have been designed to help in its obliteration. The value of fat lies in the consumerism of those that strive to lose it, but rarely do, and so the wheel keeps spinning.

Neoliberal governing emphasizes control and responsibility over one’s life. It is permeated by the market and the individual is increasingly perceived as consumer and entrepreneur. In the 2010 campaign, the fat body, usually construed as a costly body, has been turned by a curious twist into a body that can be used for gaining ‘moral credit’. The moral value of losing weight has been quantified in economic terms. This process of buying and selling fat marks the fat body and fat as something intrinsically immoral that can only be transformed into something moral and honorable when it has been lost.

Interestingly, despite of its high profile, the campaign was not a huge success. Not all the money available to “buy fat” was spent. In fact, at the end of the campaign, the sponsor decided to pay 30 euros instead of 15 per kilogram of lost fat and still only 1.4 million euros, just 14% of the potential ten million euro fund was used. Approximately 14,200 participants lost about 48,100 kilograms during the campaign. According to the news on Finnish broadcasting company YLE, 23,500 Finns were weighed at the beginning of the campaign and about 60% of those returned for the second weighing. And what about the 40% who started the campaign and who dropped out before the finish? Well, that’s what tends to happen with crash diets – they fail.