SLOW FOOD: The Becoming of a Bourgeois Utopia

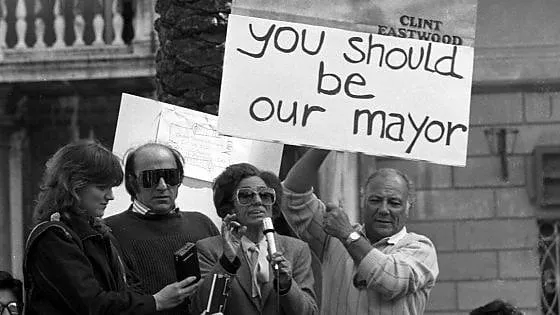

SLOW FOOD is an organization that was founded in the Italian region Piedmont in 1986 by the left activist and sociologist Carlo Petrini. It has developed from a small cultural association into an international brand that combines entrepreneurial structures with a global vision of ‘better’ food. As this post will argue, its history also highlights the cultural-political contradictions of Italy’s bourgeois left. An important event that is frequently mentioned as the symbolic founding act of SLOW FOOD is the so-called “Battle of the Piazza di Spagna” on March 20, 1986, when people were rallying against the opening of Italy’s first McDonald’s restaurant at the Piazza di Spagna, the most prestigious address in Rome. Next to Petrini, protestors included Italian high…