Until today German-style beers, beer gardens, and festivities such as the Bavarian Oktoberfest enjoy a high reputation overseas. However, according to the Beer World Cup – one of the greatest of its kind taking place every two years since 1996 – the best German-style beers are not brewed in Germany but by US-American breweries. In 2010 the gold medal in the category German-style Pilsner went to the Sierra Nevada Brewing Company in Chico, CA. And while last year the Private Landbrauerei Schönram in Bavaria brewed the best Pilsner its brewmaster Eric Toft is an American. Moreover, the gold medals in the categories Kölsch, Düsseldorfer Altbier, Schwarzbier, Märzen, Münchener Dunkel, and (Mai)Bock all went to US-American firms.

It seems that German breweries have suffered both a quality and an identity loss when compared to today’s thriving US-American brewing scene which has blossomed since the craft movement took sway in the 1980s. This is rather ironic for it were German immigrants who started the so-called “lager beer revolution” in the US in the middle of the 19th century and fundamentally changed America’s drinking culture.

Ethnicity has profoundly shaped what Americans eat and drink. While British and Dutch brewing traditions had crossed the Atlantic in the 16th and 17th century and British-style ale in particular had become the dominant drink by the 1800s, one century later German-style lager accounted for approximately 90 per cent of the national beer production and consumption (note that in the English speaking world “lager” was and is often used as a collective term for all bottom-fermented beers such as lager and pilsner). During the same period German-American migration steadily increased and as the number of breweries reached a pre-prohibition high of 4,131 in 1873, over 80 per cent of these were operated by German migrants in the first or second generation. Hence, beer became associated in the “collective memory” as a German beverage and brewers, in turn, became transcultural brokers spreading and representing the image of “the” German beer drinking nation.

On the one hand, the move away from the “heavy” ale to the “light” lager was a consumer-led process. On the other hand, it was driven by the brewers themselves who mainly used three marketing themes to promote their product: First, rural scenes to symbolize the beer’s natural ingredients, purity, and health values; second, the great brewing plants as monuments of success and technological progress; as well as third, German symbols, brand names, and drinking places to sell an authentically German and hence, superior product. Especially the last marketing strategy transformed beer into an ethnic signifier for “Germanness”: Brand names such as “Old Heidelberg” or “AdlerBrau”, stereotypical pictures of “German” barmaids holding overflowing steins of beer as well as beer gardens and beer halls with waiters in traditional “German” dresses serving “German” beer and food were used for advertising.

While US saloons were associated with manhood, crime, and corruption containing “neither bench nor chair, just drink your schnaps and then go,” as one German-American from Milwaukee complained (cited in Kathleen Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 1836-1860. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1976: 157), German-style drinking venues were known for their sociability and family-friendliness and by the end of the 19th century had been established in several major cities across the nation.

These venues did not only serve as retail outlets, they also allowed the brewers to infuse in their homeland an “old-world” atmosphere and the marketing and consumption of beer became an emblem of a constantly negotiated German-American identity. While it provided a taste of the old country in the new, it established a hybrid space where identity and ethnicity were constantly performed, asserted, and (re)invented. In particular, brewers often reduced German beer customs to those of Bavaria while promoting these in the US as a genuinely German tradition both linking them to already established American drinking customs and establishing a notion of group identity.

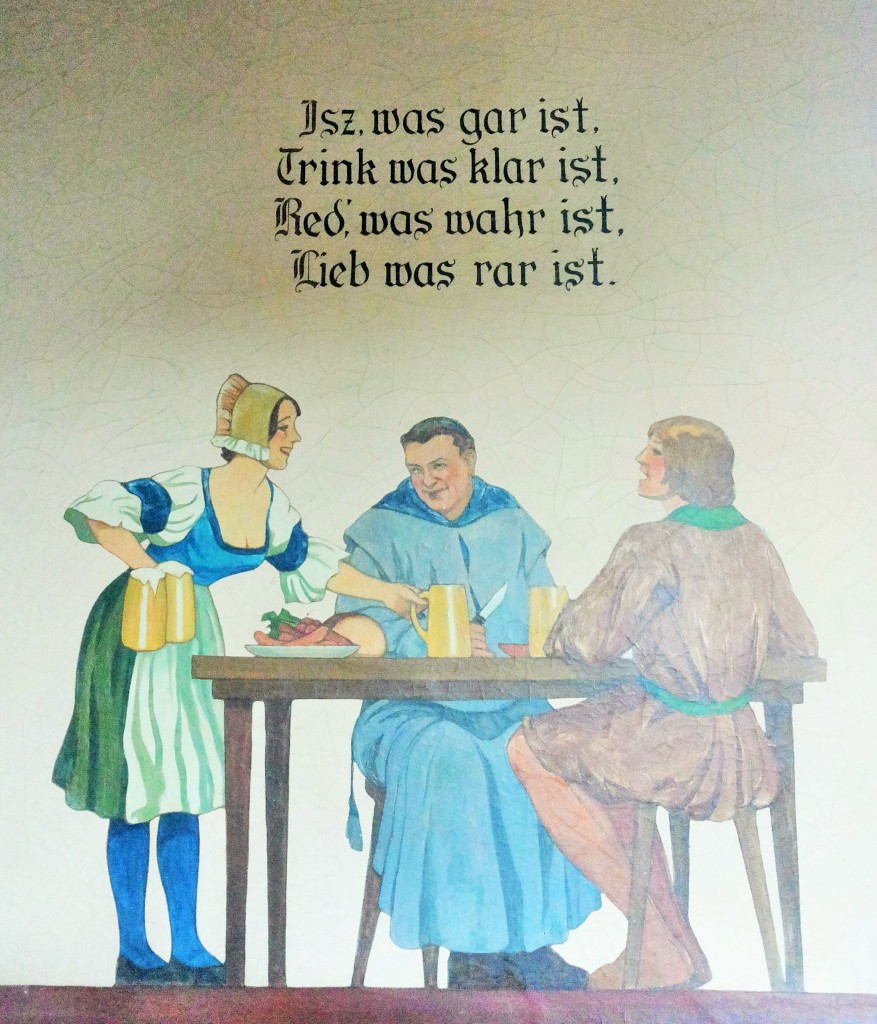

German proverb on one of the interior walls at Best Place,

German proverb on one of the interior walls at Best Place,

historic Pabst Brewery, Milwaukee, WI (Photo: Jana Weiß, 2014).

English translation: “Eat what’s well cooked,

Drink what’s pure, Say what’s true, Love what’s rare.”

And yet, this idealized and romanticized version of the “American Way of Gemuetlichkeit” suffered with the growing temperance movement in the late 19th century, but especially during the two World Wars when anti-German propaganda lead German-American brewers to present their firms as essentially patriotic American companies. The German element in marketing was nearly completely dropped and beer became an essentially American product, produced and consumed by Americans.

Since the 1950s the American beer market is dominated by a handful of (multi)national firms though today’s top four beer producers (based on 2013 sales volume) – Anheuser-Busch, MillerCoors, Pabst, and D. G. Yuengling and Son – were all initially started by German immigrants. Moreover, with the rise of the craft beer movement since the 1980s the number of breweries has constantly increased to currently over 3,400 breweries across the nation. This unprecedented boom has lead to a diversified beer market, a revival of old-style, high-quality beers, and a resurgence of brewpubs.

Thus, it is not surprising that in 2014 Jim Koch, co-founder of America’s leading craft brewing company, the Boston Beer Company (1984), which produces sixty styles of Samuel Adams, received the Bayerischer Bierorden and exclaimed in his opening address at the BrauBeviale that today the US would be the best place for beer drinkers. As the Beer World Cup biennially attests he seems to be right. While Germans hold long-cherished prejudices against the US-American “Plörre” the same seems to apply to today’s German industrial brews: weak, indistinguishable beers as against the individual, intense tastes of craft beers.

Today’s beer renaissance is led by American pioneers and Germany is lagging behind – though in the last three years German brewers have recognized the new trend. But there is a long road ahead while in the US old German-Style beers and beer gardens again flourish. For example, the Eastabrook Beer Garden on the banks of the Milwaukee River opened in 2012 and is molded after beer gardens found in modern-day Munich inviting its visitors to “experience Gemütlichkeit”. It seems that while beers produced in Germany are losing international acclaim, at least German “Gemuetlichkeit” prevails.