In May this year, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) introduced new labels that will have to be printed on most packaged food products by July 2018. In a presentation at the White House, Michelle Obama praised the label as making “a real difference in providing families across the country the information they need to make healthy choices.” Recent posts on this blog have discussed notions of transparency and choice. Today, I want to add some remarks on the history and politics of the gauge on which a lot of today’s food talk is based: on calories.

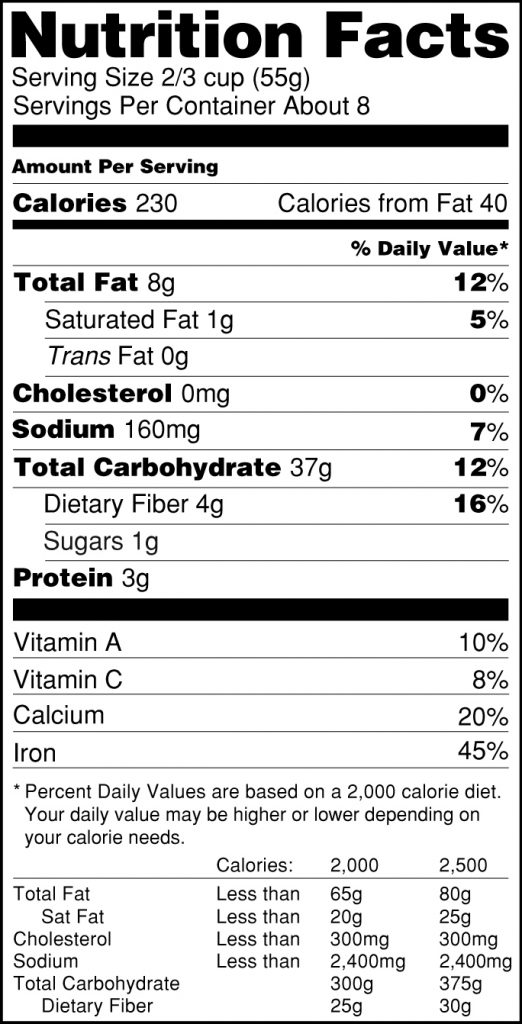

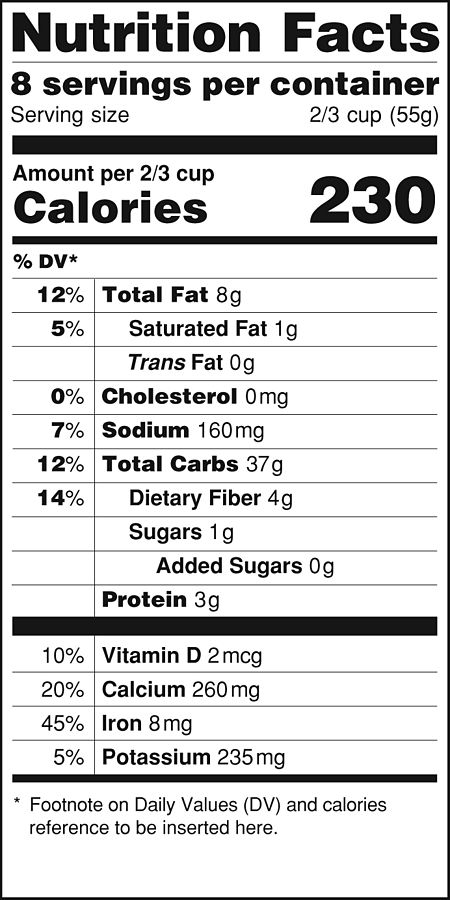

The new food label includes a line on added sugars as well as changes in serving sizes. Its most visible change, however, is the calorie count which is in much bigger and bolder type than before. As Obama and the FDA hope, this number will help consumers in understanding the food’s value and allow them to eat according to their caloric needs.

Old (left) and new label (right), by U.S. Food and Drug Administration [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Today, calories are everywhere when it comes to diet advice. Although often criticized for being inaccurate or much too complicated to count, calories set the agenda. By calorie counting, we learn, we can balance our food intake and become or stay slim – as long as we know and care enough.

However, the idea that a number on foods expresses some truth-to-be-revealed is not very old. Neither is the ideal of responsible consumers choosing wisely and budgeting their food intake according to their bodily needs. In fact, both understandings emerged simultaneously and they were and are mutually dependent.

It was in the 1890s when chemist Wilbur Atwater sent one of his students in a room-sized box made of wood and copper that Atwater’s team had set up in his laboratory at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut. For several days and nights, the student spent his time alternately exercising and resting. The scientists gave him precisely measured rations of bread, beans, meat, milk, and mashed potatoes. The whole time, they observed him through the triple-glazed window and recorded how much heat, carbon dioxide, and excretions he produced. With these experiments, Atwater determined the caloric value of food as well as the number of calories a body needed to perform specific activities.

It is important to consider the context of these early caloric experiments. In the 19th century, sciences like physiology and nutritional science were created – disciplines that focused on the human body. In times of advancing industrialism, migration and urbanization, Americans turned to scientific expertise and new methods of measuring and classifying in order to understand and improve bodies and society.

The calorie promised an opportunity to do just that. Not accidentally, devices similar to this calorimeter had been used before to measure the efficiency of steam engines. The frame for caloric research was a model of the body as “human motor,” transforming food energy into work. Calories suggested that a causal relationship between food intake and energy expenditure could be adequately expressed and improved. Experiments provided the data to develop highly standardized tables that seemed to present precise information on the fuel value of foods and the caloric needs of different bodies – mostly male bodies, by the way. According to Atwater, men “with little physical exercise” needed to consume 2,450 calories a day to maintain their physical status quo. For those “with hard muscular work”, he even advised an intake of 5,700 calories. Nutritional needs and body weight turned into norms that were seen as calculable. Because of this calculability, individuals were called upon to count.

For some people, calories and their call to properly count came at the right time. Since the 1880s, Atwater had also been coordinating a broad series of dietary studies all over the US. Surveyors weighed all the food their test subjects were eating and measured its caloric value as well as its content in terms of protein, carbohydrate, and fat. In a study of working class families in NYC, the researchers related the calories of foods to the price paid for them. They asked: How many calories could one buy for 25 cents? Which foodstuff came with the best ratio of fuel value and costs? Calories fueled a heated debate on poverty and hunger which was part of an upsurge of labor conflict. With the help of the calorie and by being able to compare different foodstuffs, reformers found that the solution to the problem of hunger was not to raise wages but to choose foodstuffs more carefully. Atwater suggested that workers should substitute expensive cuts of meat with cheap ones – or green veggies with oatmeal. Thereby, they should meet their caloric needs in a much cheaper way, and thus keep within their budgets. Here, calorie contributed to cap wages.

However, the calorie proved not only powerful in regard to the politics of poverty. It also prompted individuals to work on themselves. By suggesting a calculable and, thus, manageable relation between food and body weight and shape, the calorie suggested that individuals could and should manage their food intake properly. In the early 20th century, the alleged calculability contributed to associating fatness with self-indulgence and failure. When the calorie permitted a proper accounting of one’s diet and people were and remained fat, it seemed that they themselves were to blame. The author of one of the first calorie-based diet manuals, Lulu Hunt Peters, described fatness as a “disgrace” because, in her view, people could know and do better. She asked her readers to alert people on the streets they found too fat, and to tell them about calorie counting.

In the early 20th century, the new knowledge about calories facilitated a new form of self-conduct. At the same time it made this self-conduct seem appropriate and necessary and helped to create the ideal of self-responsible consumers caring about their own body and health. When the New York Times was somewhat relieved about the comparatively low calorie count of Hillary Clinton’s Chipotle choice on her campaign trail in Ohio, it was about more than just her individual health and weight (the latter having been discussed earlier). On trial was her ability to conduct herself properly. Especially by comparing Clinton’s choice to that of the “average American,” the New York Times presented Clinton as a responsible consumer. What calories do is producing and maintaining norms of bodies and selves – norms that contribute to the creation and affirmation of social hierarchies and travel through the seemingly objective numbers on nutrition labels.