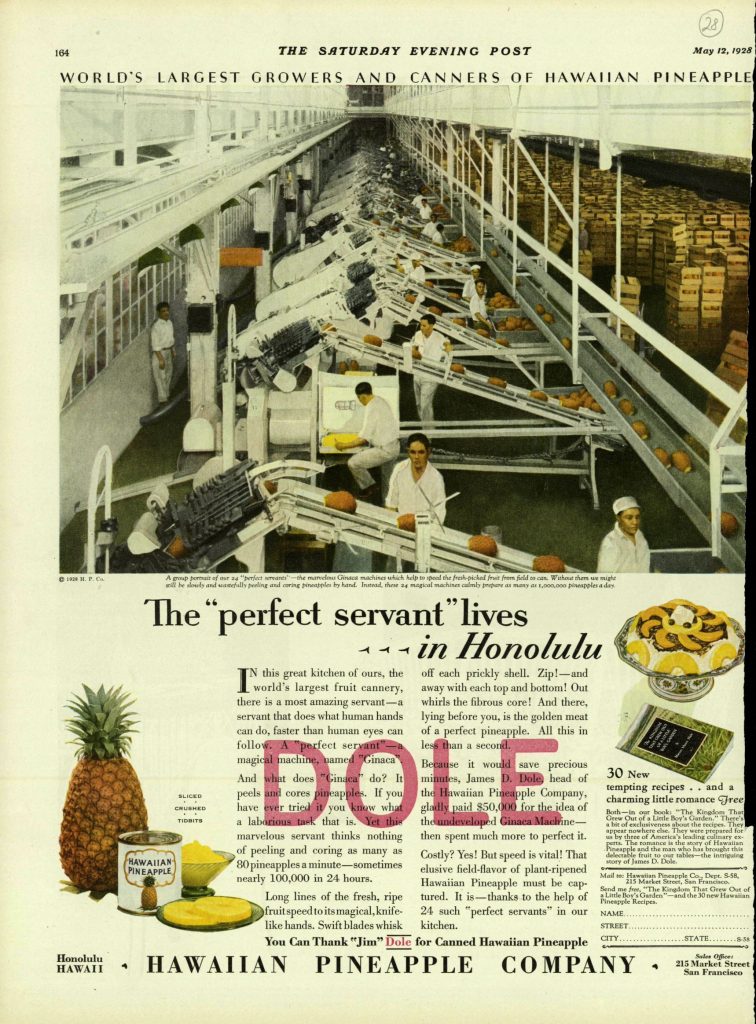

In 1928, the Dole Hawaiian Pineapple Company published an advertisement of a pineapple cannery that declared in bold, black letters: “The Perfect Servant Lives in Honolulu.” This advertisement was not referring to a perfect factory worker, but the perfect canning machine: the groundbreaking Ginaca invented by engineer Henry Gabriel Ginaca, which profoundly advanced the pineapple canning process in the early twentieth century. The 1928 advertisement showed an aerial view of the Ginaca machines, with pineapples descending down long, slender conveyor belts. Inside the Ginacas were tubular slicing knives that could cut and can as many as 100,000 pineapples a day. Eventually, the Ginaca not only cored, peeled, and sliced the fruit into neat squares, but also sized it to fit the diameter of the can. These machines were the pineapple industry’s highest achievements, bringing together ideas about modernism and clean design. By dubbing the Ginaca as “the perfect servant,” and claiming that it “does what human hands can do, but faster than human eyes can even believe,” this advertisement showed how human involvement in production was minimized. The focus on pineapple machines, and not pineapple workers, was a maneuver on part of the Dole Hawaiian Pineapple Company to navigate mounting concerns at that time about contamination in the canning industry.

Public worries about contaminated pineapples were likely inflated by fears of foreign contamination in the cannery by the industry’s immigrant workers. Few scholars have considered how prejudices against the industry’s majority Asian immigrant workforce influenced concerns about cleanliness in the pineapple cannery. Since the late nineteenth century, consumers in the United States had complained about Asian food workers being filthy and loathsome. In the 1870s, consumers distrusted the purity of sugar produced by “heathen Chinamen” standing ankle-deep in syrup. In the 1880s, consumers protested California wine made from grapes treaded by the bare feet of “celestials.” By the 1900s, food companies were so determined to eliminate Chinese laborers from the fish industry that they invented the “iron chink,” a machine that cleaned and canned fish without human intervention. Using a racial slur for this invention underscores the bigotry toward Chinese laborers and desires to create mechanical surrogates for them. These prejudices were further reflected in the Asian Exclusion Act of 1924 that prohibited immigrants from Asian countries coming to the United States. The Dole Hawaiian Pineapple Company may have tried to mitigate racial anxieties and maintain the purity of its product by diminishing the role of Asian laborers in its advertisements, instead highlighting Ginaca machines.

Though their role was diminished, the representation of Asian and other non-white workers in company advertisements was a visual testament to their cleanliness and efficiency in the cannery; the 1928 ad presented clean employees standing tall and confident, conducting their work with integrity. Articles about the pineapple cannery confirmed that “rubber gloves, clean white aprons and caps are worn by every worker,” making sure that “bare hands never touch the golden fruit.” One article even mentioned that women canners laundered their clothing every day. Advertisements showing women in white rubber gloves and white smocks not touching, but supervising the fruit’s slicing, displayed cannery workers as models of sanitation who maintained the highest standard of cleanliness. The workers’ uniforms were as white as the spotless Ginacas, and thus worked to assuage prejudices about the filth of immigrant workers. Showing non-white workers in white clothes among white walls in white canneries literally whitewashed them and defused the threat of immigrants in factories, whose placement next to machines spoke directly to the minimal contact between workers and pineapples. The Hawaiian Pineapple Company could have edited out laborers of color from its advertisements, but it chose to foreground them, declaring that they had an important role to play in the pineapple industry. Placing them in the foreground also declared that the Hawaiian Pineapple Company had regulated and thus controlled its Asian workers that many viewed with suspicion and hatred.

Advertisers for the Hawaiian Pineapple Company used another method to manage anxieties about its workforce: it glorified the pineapple cannery as a paradigm of racial harmony. The 1928 advertisement, for example, showed well-mannered laborers of many nationalities, working harmoniously in organized factories. Reports celebrated the racial diversity of cannery workers, saying:

It is a common sight to see women of four or five different races working side by side on a packing table. Race prejudices are rarely in evidence in the cannery—Japanese, Chinese, Koreans, Hawaiians and Portuguese all working peacefully together under foremen of different nationalities…we daresay that nowhere else in the world will one find so many races and mixtures of races gathered together in one plant as are found in a pineapple cannery in Hawaii. (National Trade Journals, 1922)

Presenting the pineapple cannery as a model of racial equality shaped by workers of all descent—including Asian—directly challenged the most recent Asian Exclusion Act of 1924, the harshest immigration legislation to date. Pineapple and sugar companies relied heavily on Asian laborers, so they lobbied for modifications to the Exclusion Act in order to recruit more immigrant laborers. But at the same time that the Hawaiian Pineapple Company challenged racist policies and advocated for immigration reform, it also disenfranchized its workers by offering them low wages and few benefits, pitting immigrant communities against one another in the competition for jobs. Such practices continued the legacy of colonialism in Hawai’i where indigenous peoples had also been subordinated and exploited by American forces since their arrival in the nineteenth century. For many people in Hawai’i, the portrayal of it as a multiracial paradise was not their experience. Advertisements, on the other hand, displayed pristine canneries worked by a happy melting pot of people from different cultures that may have tempered anxieties about its immigrant labor force.

The 1928 advertisement of Dole’s “perfect servant,” therefore, is not so alluring beneath the surface of the sparkling white walls, gloves, and machines in the pineapple cannery. Such advertisements were carefully crafted by companies to not only increase product awareness and boost sales, but to negotiate prejudiced attitudes about those who canned and cultivated these foods. Advertisements for the Dole Hawaiian Pineapple Company were such a powerful tool in the early twentieth century to accomplish these goals because they displayed seductive pictures that grabbed the viewers’ attention and sold them on picturesque images of pineapple production while gingerly stepping around issues of race and immigration.

Sherrill Kushner says:

Well written expose’ on a topic that is timely today…”foreigners” in our workforce and how they are treated.

Ralph Stein says:

Amazingly you left off the history of Hawaii and how Dole helped to take over Hawaii and get their Queen imprisoned in her own castle!

Shana Klein says:

It’s in the book! Check out “The Fruits of Empire: Art, Food, and the Politics of Race in the Age of American Expansion” at: https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520296398/the-fruits-of-empire

Jamie cohen says:

Great read. Shocking.

Anandhi says:

Dear Shana, you have proved your love for art history of America through your words. This article has been penned so beautifully with regards to the Ginaca canning machine invented in 1928. Thank you for giving us a complete walkthrough of the advertisement and its creatives along with its meaning that Dole Hawaiian Pineapple company has tried to bring out. It was a beautiful read into the history.

Shana says:

Glad you enjoyed it! Thanks for reading. -Shana

L.Leong says:

I worked at Dole Pineapple Cannery in my youth as a summer seasonal worker in the 1970’s. What you don’t see are the thousands of non-white workers on the other side of the wall on the left — the realm of the “trimmers” and “packers”. They don’t talk about the “pineapple rash” on the arms of the workers from constant contact with the acidic juice. You also can’t feel the heat of the Hawaiian summer under the tin roofs or the smells of pineapple which permeated the entire factory, But it was a clean environment. It also offered summer employment to thousands of young people at the end of the school year. It helped pay my way through college. All that is gone now and the original building which housed the Ginaca Machines and trimmers and packers is a movie theater. The huge Dole Iwilei campus has been broken up and is home to a Costco.

Shana says:

Wow, thanks so much for sharing your experience. I wish there were more oral histories and archival research on the subject to capture your perspective and that of others. -Shana

Laurence Kaufman says:

An interesting and informative read. I worked for Dole 1960-65 as Director of Merchandising Services in the San Jose mainland marketing headquarters. The late Bill Quinn, former Governor of Hawaii when it transitioned from being a Territory to Statehood, became the president of Dole. Looking back on it now I realize what a privileged white-male organization it was. But as I kept reminding my children and grandchildren nothing remains constant. The fruit orchards of San Jose, Mountain View, Los Gatos, are long gone and of course, so is the fruit cannery at 4th and Virginia Streets, all to be replaced by “Silicon Valley.” By the 1950’s Dole realized the day was approaching when it would be economically not viable to grow and process pineapple in Hawaii and they attempted to grow it in Mexico– the DoleMex project failed for various reasons.

Shana Klein says:

Laurence, thank you for sharing your experiences. You reveal a lot of truths about the organization and also its future outside of Hawaii. I think the San Jose headquarter had artist Georgia O’Keeffe’s painting of the company pineapple on display. I wonder if you ever saw it. It is a fascinating company with an equally fascinating history.

amsgold smith says:

amazing content such an very informative post