In the decades around the turn of the twentieth century, hikers, backpackers, and mountain climbers on the United States’ east and west coasts spoke as excitedly about campfire food as they did about the continent’s ‘pristine’ wilderness. In hiking accounts and articles in outdoors magazines, early recreationalists explored what food meant to them. For many, trail fare and campfire cooking were about more than sustenance; they provided a means to transcend contemporary society’s gendered expectations about food and its consumption.

The early hiking clubs of the United States were not overtly exclusionary in the ways that their European contemporaries were, but resistance to women’s inclusion was evident. In their early years, Massachusetts’s Appalachian Mountain Club (est. 1876), California’s Sierra Club (est. 1892), and Oregon’s Mazamas (est. 1894) were all male-dominated institutions, reticent to allow women to occupy leadership positions or undertake hikes that were deemed too strenuous.

Physical assessments of climbing ability no longer favoured men over women by the end of the 19th century, but food remained a topic where male hikers could express contemporary suspicions about female frailty. Doubts about the fortitude of the female digestive system and an inability to endure campfire fare appeared in hiker correspondence and expedition reports. Writers argued trail coffee would make women too nervous to climb, and that consuming certain foods at certain altitudes – such as eggs and beans – would deplete female stamina. There were also doubts that women’s’ domestic abilities were not adaptable to the rigours of the American wilderness. Appalachian Mountain Club councillor, Augustus Scott, suggested the way home foods were modified for the mountainside would be rejected by female hikers. He believed that oatmeal without milk would not be tolerated because of its supposed “coarseness.” Another hiker expressed concern that women, increasingly used to buying food products rather than butchering and preparing animals for meals at home, would shrink from the task if required to do so in the wild.

These assessments did not hold up in practice. As Helen A. Brown details in Women on High, Scott’s expedition along New Hampshire’s Twin Range in the late 19th century was saved from disaster because two female members of his group had conserved rations and water. Other women in the Appalachian Mountain Club happily prepared game for the fire as they helped mark and improve trails in New England in the 1890s. In California, wives carried pots and pans through Yosemite as the Sierra Club contested dam construction in the 1910s, publishing accounts of their experiences in issues of the Sierra Club Bulletin. This is not to suggest women were simply brought to the wilderness as begrudging cooks. When the Mazamas hiking club ascended Oregon’s Eagle Cap in 1918, 14 of the 25 participants were female, as were 11 of the 21 participants reaching the top of California’s Mount Ritter in 1921.

Women on trips like these found the consumption of trail fare joyous, not challenging. “Food is near the top of the list of […] recollections,” recalled mountaineer Charlotte Mauk. For early female hikers, there was a sense of liberation in becoming ravenously hungry and eating wantonly. The “manless climbers,” women who ascended the High Sierras in the 1920s and early 1930s, relished the freedom that followed a challenging climb. Their exertions allowed them to embrace a campfire culture typically reserved for males, and they relished acting like the starving Sierra Club men that hiker John White called “meat hungry warriors.” This sense of behavioural freedom did however reflect how early 20th century America’s shifting rules of consumption were transplanted into the American wilds. Treating extra food as a reward for strenuous labour legitimised emergent nutritional studies that stressed the calorimetric construction of female bodies.

Outdoorsmen – typically privileged, white American males – had a similarly complex relationship with trail food in the early 20th century. Authors writing for recreation magazines such as Outing and Field and Stream between 1900 and the early 1920s detailed particularly disastrous dishes, dinner mishaps, and even cases of self-inflicted food poisoning. A sense of excitement and exploration was common in these writings. Author Earle Forrest, in an article entitled “Fancy Cooking in Camp,” boasted of his recipes: “do not wait until you go into the woods to try these. Bake a big mess at home!” One author spent seven paragraphs lovingly describing how best to cook venison, while another (anonymous) contributor begged readers to “consider the case for cheese.” Other writers had running disagreements over whether coffee or tea was the superior trail beverage, or how best to cook beans. The tone of these articles felt anomalous nestled alongside articles in recreational publications that typically reflected on sporting achievement, conservation, and American citizenship. They also starkly contrasted with the discourse about calories and nutrition that was emerging from experts at the time. While outdoors magazines did incorporate some of these discussions – caloric density versus carry weight was of interest to hikers – far more wilderness culinary writing emphasised the sensory pleasures and emotional experience of cooking. It allowed male authors to express themselves in a way not allowed by contemporary outdoors masculinity, which focused on cooking ability as evidence of self-sufficiency.

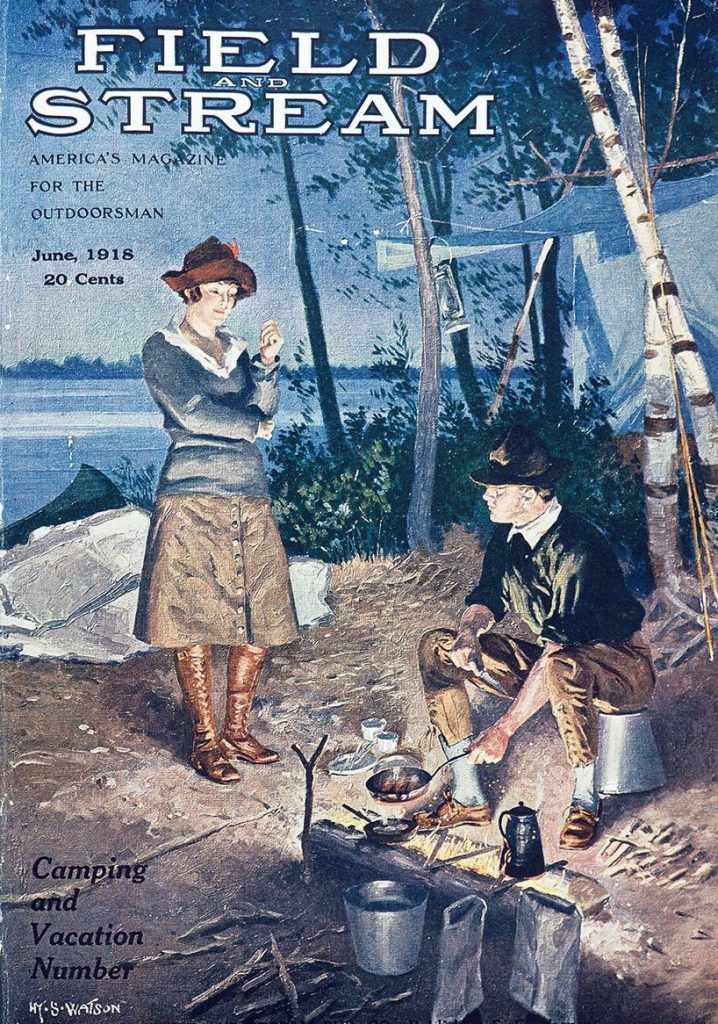

Many of these male writers recognised their culinary exploits invaded a traditionally female realm of expertise. They referenced wives and mothers, crediting their culinary ability and for awakening them to the sensory pleasures of cooking. E.L. Chicanot said in a 1922 issue of Outing that his failures with breadmaking on the trail convinced him of ‘the importance of women’s work.’ The June 1918 cover of Field and Stream ably depicted the actual or imagined relationships expressed by many of these articles, as an outdoorsman conducted the camp cooking while a nearby woman acted as an expert consultant. There were, of course, limits to this sense of male indebtedness. Few of the expert female culinarians cited by sons and husbands saw their own voices make it into print.

The sense of personal freedom attached to discussing and consuming trail food did not last and was in obvious decline by the mid-1930s. Within recreation publications, debates about caloric intake and the nutritional value of trail foods increasingly replaced sensory explorations. Larger cultural shifts also ensured that stepping outside traditional gender boundaries in nature through food became more difficult. As the United States crept toward mid-century, vastly more Americans headed into the great outdoors, but visitors predominantly went as families. Increasingly, labour on the trail mirrored domestic responsibilities. For recreational groups like the Appalachian Mountain Club and Sierra Club, this meant men headed out from camp to tackle the more challenging hikes and ascents. As Susan Schrepfer has noted, women prepared food at camp, watched over children, or picked wildflowers. The increased presence of female hikers from the 1930s onward did hasten the erosion of the American wilderness as a male centric space. Yet for most women, their first experience of remote nature was not as mountaineers or adventurers, but as wives, mothers, and cooks.