Blitzing, blasting, shredding, and, of course, pumping. For bodybuilders of the 1980s, these verbs were not just descriptors, but a way of life. In 1977, Pumping Iron, a docudrama featuring Arnold Schwarzenegger, helped American men fall in love with bodybuilding. Where Jane Fonda encouraged a boom of aerobics exercises for women, Arnold and his rag-tag group of muscular merry-men became the face of a new public interest in musculature.

Bodybuilding grew as a sport, but just as importantly, as a hobby. This was a time when fitness became ‘serious leisure’ and, as multiple historians have affirmed, a time when individual health and fitness became a priority and a means of claiming social status. Muscular and lean bodies came to become a signifier for desirable, hardworking personalities. For this reason, scores of individuals used bodybuilding diets to sculpt their bodies without the desire to compete as bodybuilders, but to create muscular bodies through ‘bulking’ and lean bodies through ‘cutting’. This involved either eating an excess of calories (bulking) or severely restricting calories (cutting)

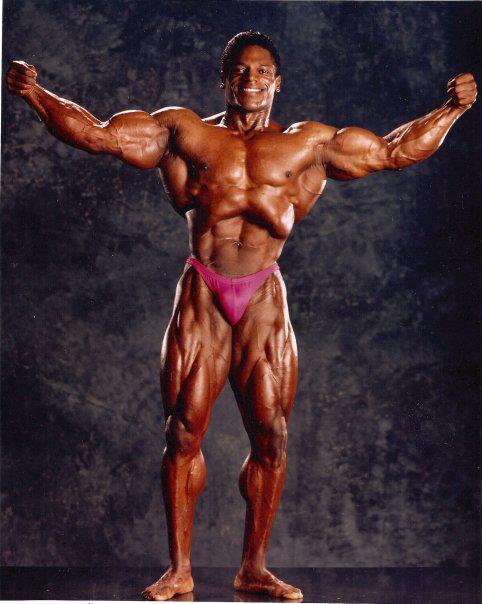

Already in the 1960s and 1970s, diets had been tightly monitored by competitive bodybuilders and their coaches but without reference to calories and with greater variety in terms of diets (as evidenced by the promotion of high fat diets during this period). A decade later, the predominant diet was low-fat with strict caloric monitoring. It is worth stating that this monitoring, when it came to weight loss, brought even more extreme levels of leanness to the sport. The 1980s was the first time in bodybuilding history that athletes appeared on stage with striated glute muscles. This was an extreme never before seen and one celebrated as a victory of strict calorie counting.

Jetman 11 at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

To understand why bodybuilders, and those following bodybuilding diets, took to such extreme measures, it is important to understand the broader American food and fitness climate during the 1980s. While becoming increasingly popular in American life as a pastime, as a competitive sport, bodybuilding became increasingly extreme and alienating to the larger public. When in the 1980s, athletes appeared on stage with striated glute muscles, this meant that their bottom contained such low levels of body fat that it was possible to see the muscles clearly defined. This had never been seen before within the sport and reflected a new, and dangerous, trend.

No Fat Please, We’re American

Two overarching food trends in the United States influenced popular bodybuilding diets in the 1980s. The first was the American aversion to dietary fat and the second was the growing commercialization of dietary supplements. During the 1980s, nutrition experts and advertisers began to promote low-fat diets as a solution to growing American fears about heart health and longevity. Backed by the scientific studies of Ancel Keys, whose comparative studies of diets and health across several nations seemed to favor low-fat diets, those had become part of established medical and public health doctrine by 1980. Moreover, a low-fat food industry capitalized on the American resolve for low-fat diets, while reinforcing the message that they were significantly healthier than high-fat diets.

Equally influential for the rise of bodybuilding diets was the growing importance of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in America. More specifically, CAM diets and supplements were marketed from the 1960s as an effective antidote to the same American ills that low-fat diets sought to target. Vitamin C and B vitamins were promoted as an answer to fears that American farming practices had devitalized American soil and that American foods were no longer as nutritious as before. Coupled with this was a growing interest in using ‘mega dosing’ with vitamins and minerals to achieve desirable health outcomes. In the 1960s, for instance, Nobel prize biochemist Linus Pauling claimed that mega-doses of Vitamin C could even cure illnesses such as cancer.

Bodybuilding in America had been influenced by supplement sales since the 1960s, but the broader embrace of dietary fat clearly shifted practices. From the first Mr. America bodybuilding show in 1939, bodybuilders had either used a high-fat diet, or one in which fat was not particularly restricted. During the 1980s, best practice shifted to low-fat diets and, reflecting the influence of CAM voices, megadoses of supplements.

Building Muscle Through Food

During the 1980s, bodybuilding was dominated by a single federation, the IFBB. Founded in the 1940s by Quebecois entrepreneurs and brothers, Ben and Joe Weider, the IFBB had, by the 1980s, an effective monopoly over the fitness industry. Not only did the federation run the most important bodybuilding competitions (including the sport’s annual showpiece, the “Mr. Olympia” show), they also produced the most popular and widely read bodybuilding magazines. As Alan Klein, a sociologist who reported on bodybuilding during this time made clear, the Weiders were the kingmakers of the sport. Becoming an endorsed “Weider athlete” was the goal of many aspiring bodybuilders. Notably, the Weiders’ business empire also promoted nutritional supplements, suggesting to readers that “Weider athletes” needed workout powders and pills to achieve the body they desired.

How were individuals encouraged to eat and bulk up? The most obvious shift during this period was a growing interest in calorie counting. Although bodybuilders had long engaged in “bulking” phases, in which they consumed an excess of food, this was often done with references to meals — that is, they were told to eat an additional meal on top of their regular diet. During the 1980s, there was an explicit shift towards calorie counting and bulking through an excess of calories (i.e. to eat 500 more calories a day). Calorie counting, which had been a most significant weight-loss tool throughout the 20th century, was now encouraged for those seeking to increase their weight.

Professional body builder Lee Labrada explained in 1991 that “the key is to never eat many fat foods. My pre-contest diet contains no more than 5% fat. The calories vary between 2,400-3,500 pre-contest; 3,800, off-season.” Carbohydrates were the cornerstone of these diets, but not any carbohydrates would do. They had to score low enough on the glycaemic index (which is a measure of how quickly a food would spike one’s blood sugar levels). High protein, low fat and a high to medium intake of specific carbohydrates were in vogue.

An often-undiscussed change in bodybuilding diets during this period were anabolic steroids and a variety of other performance enhancing drugs. While bodybuilders had been using anabolic steroids to increase their muscle mass since the 1960s, several scholars have noted an influx of new weight-gain and weight-loss drugs toward the 1980s. A prime example of how prevalent this issue was can be found in the publication of bodybuilding coach Dan Duchaine’s Underground Steroid Handbook in 1981. This book was a cultural success, enjoying several re-editions and has been credited with making drug use more accessible for gym goers in general. This prevalence of chemical supplements was reflective of a new obsession with the body beautiful in American fitness.

As bodybuilding as a practice became more popular in American life, the sport became more niche and arguably dangerous. Thus began a split between the popular practice of building muscle and losing weight versus those who took to the pursuit as a sport. For these athletes, their dietary habits – often aided by chemical substances – became increasingly exclusionary and restrictive. Eating disorders were not encouraged but one could certainly classify the diets promoted as a high measured form of disordered eating. The push for bigger, and at the same time leaner, bodies necessitated an increasing medicalization of the body wherein meals were measured to the very ounce, foods split based upon their macro-nutrient profile, and bodies injected with foreign substances. The body became the outcome of rigorous training, restricted eating, and reactive chemicals.