Note of the editors: This is the 100th entry in our blog. We are grateful to all of our contributors for making this possible and hope to have hundreds more entries to come. If you’d like to contribute, don’t hesitate to get in touch via proposals@nullfoodfatfitness.com. We appreciate your contribution!

Save the planet by eating? In recent years, a new diet has been making the rounds among nutrition experts and the popular media, one that promises to do just that: simultaneously save the planet and human life on it by eating a diet based largely on whole grains, vegetables, dairy, fruits, legumes, and nuts, while avoiding added sugars, processed fats, red meat, and refined grains (not too many surprises here!).

presented in the 2019 report “Food in the Anthropocene”

by the EAT-Lancet Commission

The “Planetary Health Diet,” praised as “the first science-based diet that tackles both the poor food eaten by billions of people and averts global environmental catastrophe” was proposed in 2019 by the EAT-Lancet Commission, a group of scientists from different countries and disciplines. It is premised on the diagnosis of a double, entangled crisis of food in the Anthropocene: While hundreds of millions of people worldwide suffer from inadequate nutrition and deficiency diseases, the global food industry is contributing to environmental degradation on an unprecedented scale. Responsible for up to 30 % of global greenhouse gas emissions and 70 % of freshwater use, food production further undermines the ability to feed a growing population. The Commission therefore called for a “global dietary transition” to address these related challenges and proposed a “universal reference diet” that would be both healthy for humanity and sustainable for the planet.

Challenging the destruction of the environment by the global food industry is essential. However, the Planetary Health Diet risks undermining its very goal, some scholars argue. Let’s have a look at their critique that the proposed diet promotes a rather narrow biopolitical and (neo-)colonial model of human health, planetary resources, and global orders.

Narrowing Down Food to Nutrition

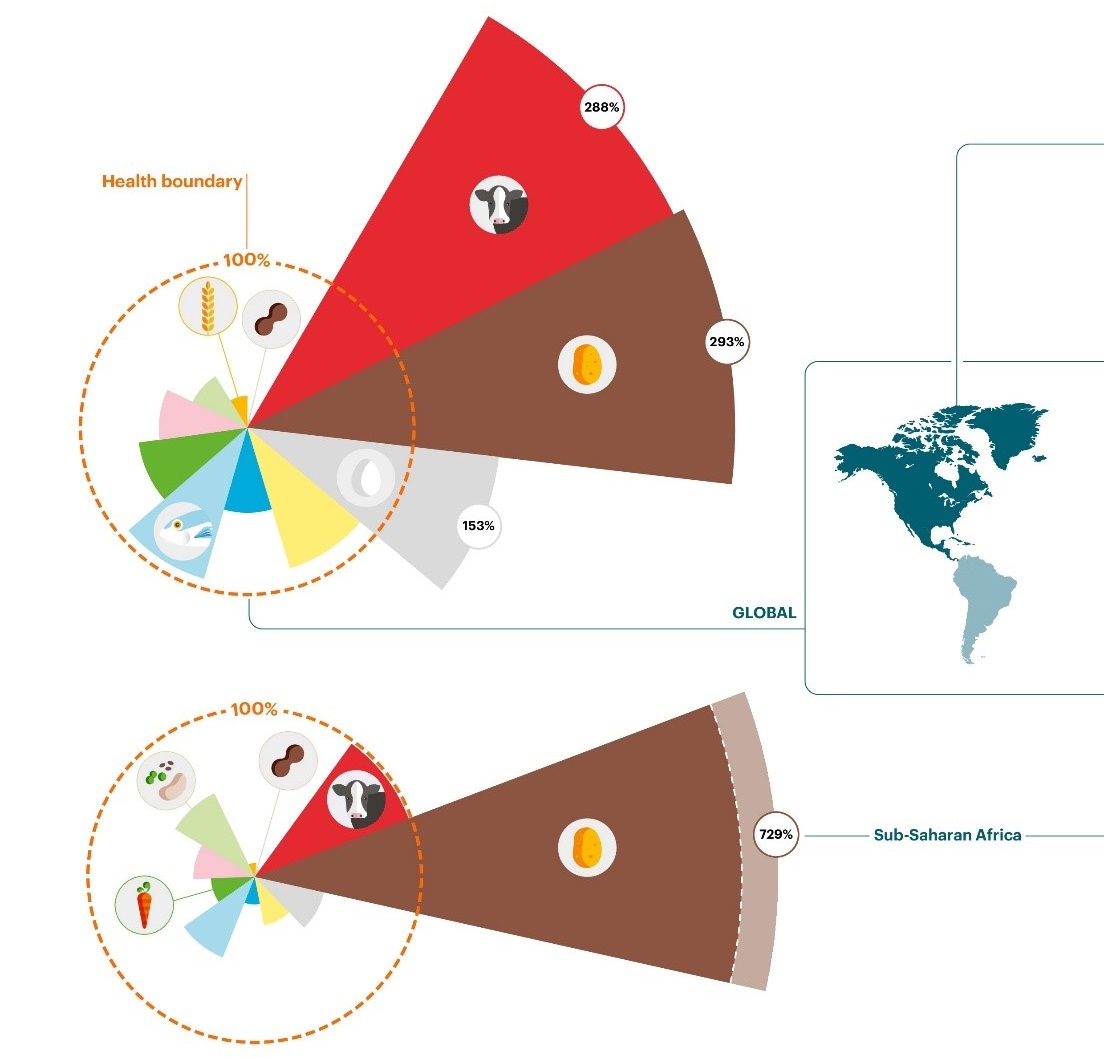

The “Planetary Health Diet” is based on two sets of quantifications that target both the consumption and production side of food. The first set quantifies the amounts of the foods an individual can eat each day for a healthy and sustainable diet: 2,500 calories, 232 g of whole grains, 300 g of vegetables, etc., sometimes allowing for larger ranges (between 0 and 500 g of dairy per day is recommended). Second, the Commission used the framework of planetary boundaries – critical limits for human activity on the planet, introduced by scientists in 2009 – to develop targets for a sustainable food production, such as a maximum of greenhouse gas emissions, fertilizer or water use.

Both sets of quantifications were, as the Commission claimed, critical to making the Planetary Health Diet something that could be acted upon. And yes, decades of research on governance by numbers has demonstrated that quantification does much to raise awareness and put issues on the political agenda by making them visible problems that can be addressed through targeted interventions. Environmental historians have shown, for instance, how numbers were crucial in turning environmental destruction into a problem of global political significance.

At the same time, through these quantifications, the Planetary Health Diet very narrowly reframes the nexus of food, health, and human-nature relationships. Translating a complex, qualitative problem into a set of numbers, promotes a “nutritionist” perspective that reduces food/health to something “amenable to economic analysis and technological solutions.” They allow only those things to become evidence that can be measured and, allegedly, managed, thereby reducing the diversity of possible human relationships with ‘nature.’

Such a technocratic perspective is also evident in the set of solutions and policies proposed by the Commission. Among them is the intensification of agricultural production – in order to stay within the limits of arable land – and the expansion of global aquaculture. Ironically, the suggestions sound like calls for a more efficient exploitation of resources. While planetary health offers an opportunity to break with ideals of limitless growth and human mastery over ‘nature,’ the solutions of the Planetary Health Diet perpetuate the call to take control, “nourish[ing] the Promethean desire to push back these limits rather than forcing us to see them as an opportunity to build a different relationship with the living world.” Scholars and activists have criticized such “fixes” as working toward the resilience of a capitalist-productivist model rather than taking a planetary perspective. Against this backdrop, it is less surprising that among the “strategic partnerships” cultivated by the EAT-Lancet Commission are major industry players such as Novo Nordisk and Nestlé – companies whose environmental, social and health impacts are the antithesis of any convincing planetary lens.

Saving Oneself with Western Guidance

The “universal reference diet” suggested by the EAT-Lancet commission, while intended to be adjustable to “all food cultures and production systems in the world,” homogenizes human relationships to food by making them commensurable. The Planetary Health Diet, like the broader planetary health program, is sustained by its claim to universality. In an episode of the Lancet podcast, Commission member Tim Lang, a London-based professor of food policy, insisted that “everyone” needed to get involved: “Whether you’re in Malawi or Manchester, or the rich parts of New York City, or in very poor areas of India, […] we’ve all got to address this.”

Together with the numbers, these universalizing moves obscure the fact that not everyone is equally responsible for environmental degradation or equally capable of complying with the proposals. Scientists have argued that the adoption of a Planetary Health Diet is “unaffordable to at least 1.58 billion people and […] more expensive than a nutritionally adequate diet,” pointing to the limits of its individual and collective appropriation. Moreover, the focus on individual diets further shifts the onus of responsibility to the individual, suggesting that a large part of “saving the planet” lies in individual dietary choices rather than in larger transformations of capitalist and neocolonial inequalities.

The Commission’s very particular perspective on nutritional health is aptly expressed in its recommendation of the “Mediterranean diet” as a “well established” version of the reference diet. Although the commission members insist that they’re not suggesting that the whole world should eat the Mediterranean diet, it is held up as an example of ideal nutrition, betraying the situated nature of the Commission’s work. Most of its members come from Western, high-income countries, and its calculation of the reference diet was based on studies conducted mostly in Europe and the United States (as the report itself notes).

To be sure, the EAT-Lancet Commission did attempt to address global inequalities in its report. For example, in proposing a kind of global budgeting, it emphasizes that the global North must reduce red meat consumption and fertilizer use in order to increase both in certain regions, such as Eastern Africa: a region where people wouldn’t get enough nutrients from plant-based foods and where animal-based foods should be promoted rather than restricted. However, this global mapping of differences between a region’s current dietary status quo and an “optimal diet” tends to perpetuate (neo-)colonial hierarchies, suggesting that people needed to overcome a state of (nutritional) underdevelopment towards an allegedly universal—but highly particular, Western—standard. It is yet another example of Western expert panels producing authoritative knowledge about what foods are appropriate (healthy and sustainable), thereby denying food sovereignty to Indigenous groups and thus adding to a long history of erasure of their food and health practices.

Many of the questions raised by the Planetary Health Diet are crucial. But there are more to be added: Who defines health and sustainability? And for whom? In 2023, an “EAT–Lancet Commission 2.0” has begun to expand on earlier proposals to take into account unequal exposure to air or soil pollution and access to healthy food, and it is to be hoped that they will address questions of how to decolonize understandings of proper nutrition and health. Max Liboiron has recently argued that to do this properly will require broader changes in the way science is done, with Indigenous knowledge taken seriously “as expertise rather than culture,” and an end to claiming access to Indigenous lands. If this is not done, the Planetary Health Diet, while rightly critiquing the environmental destruction of the global food industry, obscures rather than overcomes a biopolitical, resourcist, and colonial model of human health that focuses on population, human life, and “natural” resources to measure and control. Such an understanding of health and the planet had created the problem in the first place.