As I was reading the Sunday newspaper, a colorful full-page advertisement caught my eye. At the bottom sat a juicy burger. Two buns encased a thick patty stacked over arugula and topped with fresh onion rings, tomatoes, and mayonnaise. Behind the burger sat the phrase “Beyond Meat, Serve Love.” Over everything hung a headline declaring “The Next Generation of Beyond Meat is Here and It’s Not Just Loved by Those Who Have Tasted It.” As a historian who has written about food politics in Germany, I’m always curious about food politics in other places. In this case, that other place is the United States.

Caught by the color, two mentions of “love,” and, let’s admit it, that mouth-watering burger, I kept reading. Who, I wondered idly, loves Beyond Meat? Ah, it’s the five U.S.-based groups indicated by the icons scattered across the page: Good Housekeeping (a women’s magazine), the American Diabetes Association, the American Heart Association, the Clean Label Project (a non-profit dedicated to truth in labelling), and the Non-GMO Project (a non-profit dedicated to promoting foods made without GMOs). All offered endorsements and certificates that let me know I could love Beyond Meat for its taste but rest assured that the experts loved it for the health and environmental benefits it could bring me and my planet. As the Beyond Meat website informed me when I logged on, “[b]y shifting from animal to plant-based meat, we can positively affect the planet, the environment, the climate and even ourselves. After all, the positive choices we make every day – no matter how small – can have a great impact on our world.” What’s not to love (er, eat)?

However tasty it might be, Beyond Meat calls out for analysis. Let’s start with the name itself. “Beyond Meat” is a clever piece of marketing. Rather than invoking vegetarianism, a term that turns most people off, the phrase invokes meat to sell a meatless product. You can eat meat—without eating meat!

More broadly, Beyond Meat takes me back then—to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when claims about the health, environmental, and political benefits of low-meat and meatless diets proliferated. What is there to say about this past that lies beyond our “beyond meat” present and its promise of a “beyond meat” future? Here are a few alternately uplifting and sobering thoughts from the German past.

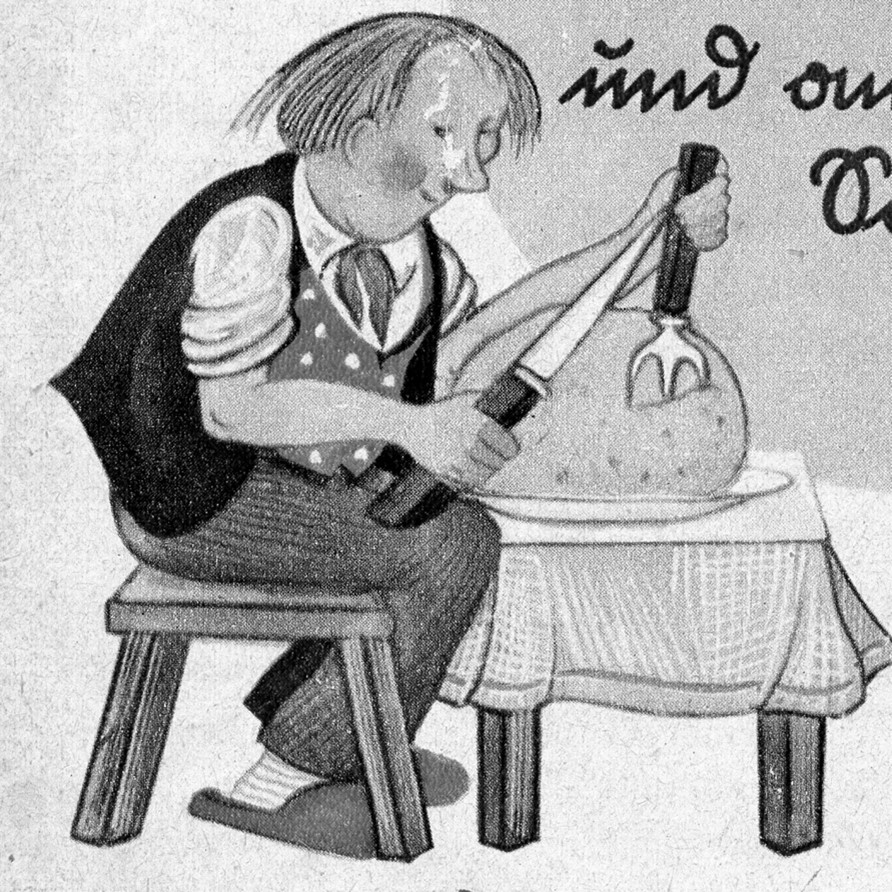

“Beyond Meat,” it turns out, has quite a long backstory. In the nineteenth century, for example, German vegetarian cookbooks liked to gloss nuts as the meat of the plant world. Flash forward to the 1930s and 1940s and we find the Nazis playing around with meatless marketing, too. There were more innocuous manifestations—like a 1940 campaign mounted by the Reichsausschuss für volkswirtschaftliche Aufklärung, a consumer education group, to get Germans to eat more potatoes and less meat. One cookbook produced by the group featured a man carving up a potato as if it were a ham. A more sinister manifestation was Biosyn-Vegetabil-Wurst, a synthetic sausage developed from paper industry waste and tested on forced laborers imprisoned at the Dachau concentration camp.

Vom ausgelassenen Apfelschmalz, vom großen Hans, dem blauen Heinrich und anderen guten Sachen zu Frühkost, Brotaufstrich und Abendessen (Berlin: Rezeptdienst, Reichsausschuss für volkswirtschaftliche Aufklärung, 1940), front cover.

To understand the ham-like potato and synthetic sausage, we have to go back to the nineteenth century. The claim that a meatless diet can improve our own health and even help the environment is an old dream of late nineteenth-century life reformers (Lebensreformer)—a loosely organized group of vegetarians, naturopaths, nudists, anti-vaccinationists, and others who sought to make life more “natural.” A shift from animal to plant foods, they believed, would bring myriad social, political, and bodily benefits. Sound familiar? No surprise: their quirky experiments in new ways to eat and farm are part of the back story to “Beyond Meat.”

Life reformers had political views all over the map. Eduard Baltzer, who coined the term “life reform,” started off as a Protestant minister so radical that he invited Jews into his own congregation. During the people’s revolutions of 1848, he came out as a republican—a dangerous position to espouse in mid-19th-century Central Europe because it might land you in prison or send you into exile. By the 1860s, after years of working with the rural poor, he embraced vegetarianism as an anti-capitalist diet. Vegetarianism, he believed, could nourish the hungry cheaply while reducing the systemic causes of inequality. Baltzer had his eye on large landowners who were getting rich producing refined sugars and grain-based schnapps that ate up workers’ wages while offering them minimal nourishment.

On the other end of the political spectrum were life reformers like Richard Ungewitter, an antisemitic nudist who believed that a plant-based diet would reverse German racial decay, and Heinrich Bauernfeind, who experimented with “natural” fertilizers made of domestic stones on the view, as he put it in a little marketing ditty, that “Ground stone fertilizer does not come from overseas / From Jews, from abroad it does not come here.”

Although these ideas about the benefits of more natural “meatless” diets started off at the social margins, they made their way into the German mainstream in a big way during the First World War, when an Allied blockade imposed from 1914 until 1919 exposed Germany’s dependence on a global market. After access to imported meats, grains, and nitrogenous fertilizers ceased, severe food shortages ensued. Into this dire situation came a panel of medical experts who had spent years studying vegetarians and their meatless diet. In a famous report called Germany’s Food and England’s Plan to Starve Her Out (1914), those experts performed a complex series of nutritional calculations to argue that Germany could survive the blockade…if consumers radically reduced their consumption of meat products.

Suddenly, vegetarianism became a matter of national security and patriotic women rose to the occasion by writing cookbooks. Hedwig Heyl, a leading social reformer better known for a best-selling pre-war health cookbook that had sung the praises of meat, published her War Cookbook in 1915. It advised Germans to go back to the low-meat habits that their forefathers had had, with no adverse health consequences, a century ago. Despite such efforts, many Germans went hungry, lost faith in their government, and started a political revolution. After the war ended, claims that up to 1 million Germans had died of malnutrition circulated widely. In the interwar years, first under democrats and then under fascists, political leaders of all stripes obsessed about ways to make sure that a nutritional disaster like this never happened again.

All of this brings us back to Biosyn-Vegetabil-Wurst. Committed to avoiding the mistakes of the past, the Nazis saw meatless meat as a matter of national security. Obsessed with racial purity, they also believed that shifting Germans to a more plant-based diet would bring both health and environmental benefits. Their experiments with meatless cookery and meat substitutes, indeed, sat alongside other experiments with early forms of organic agriculture. The Dachau concentration camp, where the paper waste sausage was piloted, for example, hosted a biodynamic herb garden farmed by camp prisoners. Dachau was Nazi Germany’s first concentration camp, part of a camp system set up to manage “enemies” of the Third Reich that eventually grew to include extermination camps like Auschwitz. Nazi interest in organic farming, in other words, was tied up with dreams of a racially pure future—a sinister “beyond” indeed. These organic herbs, raised on German soil with home-made German composts, went to feed the SS, the racial elite. Some Nazi leaders even dreamed big, of a postwar world dominated by plant-eating Germans farming the soil with ecological methods. In the event, of course, Germany lost the war and these dreams of the health and environmental benefits of meatless diets moved to other locations, only to resurface, their Nazi past largely forgotten, in the various left-leaning social movements of the 1970s.

Such are the thoughts of a German historian encountering a present-day advertisement for a meat substitute. When Beyond Meat invites me to aspire to “feed a better future” while eating “what you love, no sacrifice required,” I take it with a grain of salt. Virtuous consumption has a long history and comes in a variety of political flavors. It’s good for all of us to know what we’re being asked to swallow.

Telkom University says:

How has the history of plant-based meat evolved over time?