Through my research on black women’s exercise and fitness culture from 1900 to the 1930s, I discovered a little-known history of black fat shaming. While I expected to find that black women engaged in exercise for general health, I never imagined that some black women would craft their exercise programs for weight loss and at the same time participate in fat stigmatization. My surprise stemmed from common-sense assumptions about black people’s fat acceptance and flexible standards of beauty. Popular culture, academic studies on body image, and news outlets help to perpetuate these assumptions. R&B and Hip Hop is known for celebrating black women’s voluptuous bodies, including Drake who rapped famously he likes women “so thick that everybody else in the room is so uncomfortable.” Studies on self-assessed attractiveness often conclude that despite their higher Body Mass Indexes, black women have higher levels of body satisfaction compared to white women. More pointedly, a few years ago writer Alice Randal claimed in the New York Times “Black women are fat because we want to be.” While these examples speak to contemporary iterations of black fat acceptance, they obscure a longer history of intraracial black fat contempt. Historical evidence shows that black women did not accept fatness with open arms as some imagine. Black men were also critical of fatness and decried fat black women in the public sphere. Chronicling this history enables us to reconsider the popular and scholarly consensus about black body image and helps to peel back the layers of race, gender, class, and fat stigma that black women have wrestled with throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

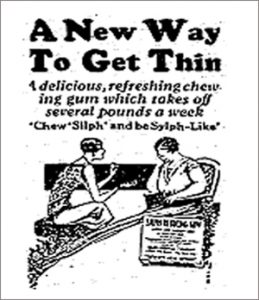

African Americans began to express fat disdain after the turn of the twentieth century, especially in the black press. Between 1904 and 1934, writers and health experts used the following terms to describe fat women in two of the most highly circulated black newspapers of the time: lazy, deranged, sluggish, mammy, out of style, abnormal, ugly, and a menace to good health. The press did not loosely attach these terms to fatness; they made them fundamentally constitutive of the fat body. In the 1910s, black newspapers advertised weight-loss products that presented a clear health-thinness-beauty triad. The New York Age often promoted the thirty day treatment for the weight-loss product “Fat Fade” that promised to “make superfluous flesh just fade away.” The advertisement appeared exclusively among women’s beauty ads for hair pomades, wigs, straightening combs, and skin lightning creams, conveying the message that a weight-loss product doubled as a beauty accoutrement. In 1918, the Chicago Defender ran ads for weight-loss pills, like one for “Tabasco tablets” whose manufacturers asserted “too much flesh is undesirable as most quite stout people will readily admit and it detracts from one’s good appearance.” It is unlikely that African Americans manufactured these products, but the fact that they appeared in one of the most vital social and political resources for black people reveals potential consumer appeal and tacit endorsement of weight reduction technology.

In all likelihood, the black press engaged in fat stigmatization as a form of protest to the ubiquitous mammy figure that inundated American print culture in the twentieth century. Media outlets portrayed the mythical black mammy as unattractive, overweight, and unfit for full-fledged citizenship. In a 1932 study on black consumerism, Fisk University professor Paul Edwards presented southern, urban African Americans with advertisements of stereotypical depictions of black women as mammies. Respondents viewed ads of smiling, overweight black women who donned handkerchiefs on their heads for pancake and soap companies. Black women respondents expressed their general dislike of the ads, but “professional” black women commented specifically that they “do not like [the] big, fat colored woman” in the ads. Unsurprisingly, class informed varying magnitudes of fat disdain. Other participants added that they generally did not appreciate seeing black women in servant roles, but the “big” and “fat” black woman elicited a visceral rejection from black women professionals.

Later in the twentieth century, other black women commented on the problem of fatness. In her essay “On Being a Fat Black Girl in a Fat-Hating Culture,” Margaret K. Bass tells of the fat prejudice and self-loathing she experienced as a child in the segregated South in the 1950s and 1960s. Bass explains that racism and Jim Crow policies did not trouble her self-perception; rather, it was her weight that evoked the most violent forms of teasing and self-deprecation. She notes that while her parents attempted to shield her from the dangers present in the South, “No one prepared me for living as a fat person.” Similarly, Johnnie Tillmon, a welfare activist, commented that fatness, in addition to race and poverty, led to her increased discrimination when she explained in Ms. magazine in 1972: “I’m a woman. I’m a black woman. I’m a poor woman. I’m a fat woman. I’m a middle-aged woman. And I’m on welfare. In this country, if you’re any one of those things you count less as a human being. If you’re all those things, you don’t count at all.”

Both Bass and Tillmon’s reflections illuminate the ways in which fatness functioned as a painful experience for some black women as opposed to a source of bodily appreciation and pride. Generally speaking, the field of fat studies, body positivity activists, and the fat acceptance movement denounce the above-mentioned examples of body shaming in their historical and contemporary forms. But for a group of people who have been regularly characterized as overweight mammies, medically obese, and fat accepting, this history of fat hostility is an important rupture in the narrative. Within the context of black women’s history, fat shame may illuminate a progressive political project that African Americans mounted to counter racist and sexist notions about black women’s excessive bodies. This history frames African Americans as co-architects of fat stigma and challenges presumptions about black women’s levels of body satisfaction, aesthetic values, and philosophies of health. To be clear, this history should not be weaponized to advocate fat shaming. But it can be used to question our long-standing cultural assumptions about fatness and help us confront pernicious ideas about black women.