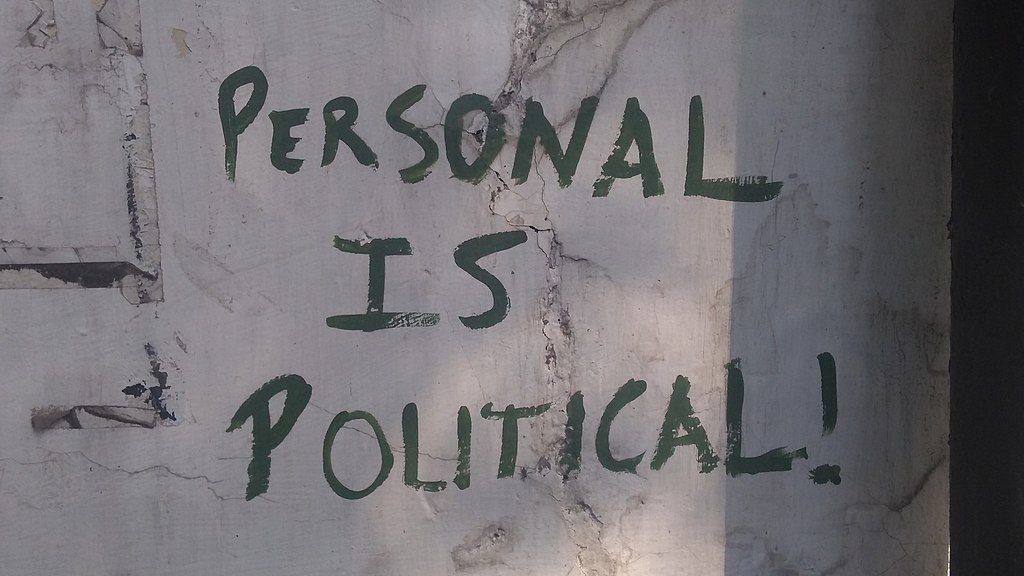

The “personal is the political,” a slogan of second-wave feminism, was also embraced by fat feminists in the 1960s and 70s. A founding member of the Fat Underground, a fat feminist liberation group, Vivian Mayer explained that they taught women to “relate ordinary ‘personal’ problems . . . to political injustices. The goal is to teach people how to support and encourage one another, and how to work together to change oppressive social relations” (xi).

In recent stories circulating around Boris Johnson’s (fat) body and his experience of COVID-19, the personal is political in a very different and problematic way. At the time of this writing, the United Kingdom has over 40,000 confirmed deaths related to the disease. The government’s response to the disease has also been widely criticized for its limited medical infrastructure, its failure to secure PPE early on, and its failure to enact policies that would slow the spread of the disease. Boris Johnson had himself come under much criticism for the slowness of his response since he flouted basic social distancing protocols early on, did not encourage the public to follow these until March 16, 2020. Boris Johnson was himself first diagnosed with the disease in late March, afterwards hospitalized and placed in intensive care. In the same period, a logic emerged in a number of popular news stories that associated obesity with the worse of the disease. By the time that Boris Johnson was released from the hospital on April 12, 2020, it had become commonplace to believe, as the governor of Florida said in order to defend re-opening his state (especially the gyms), that “obesity is, like, the No. 1 factor in whether you really get hit hard by COVID-19.”

By May 14, 2020, major newspapers were reporting that the recovered Johnson had changed his mind about national policy surrounding obesity. He has decided, reports tell us, that his case was worse because he was fat. In turn, he is committed to following a new “interventionist” national health policy against obesity. Furthermore, his new interventionist strategy was in his mind a response to the coronavirus epidemic itself. The Times, for example, explained that “Johnson’s change of heart is driven by the undeniable link between coronavirus and obesity.” The National Health Services, then, are to compile data that correlates obesity with coronavirus. Rhetorically, the stories serve to reinforce popular news reports that have made a number of associations between obesity and coronavirus. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention, for example, listed “severe obesity” as a condition that made the individual more susceptible to worst outcomes related to coronavirus. Johnson’s own personal knowledge reinforces the tenuous relationship between “obesity” and coronavirus.

This link becomes “undeniable” insofar as Johnson’s own personal experience is read through a national statistics, in which “obesity” is seen as causing the disease. Reportedly, when asked what his national strategy going forward will be for combatting COVID-19, Johnson has retorted, “Don’t be fat in your fifties.” National policy here centers on his own personal life lesson, in which a simple-minded individualistic solution is proposed. In effect, the solution to this national problem is an individual one, as the headline of one article has it, “Boris is Right – It’s time we were all more honest about our weight problem.”

These stories, obsessively focused on Boris’s body and his own experience, divert attention

from a critical consideration of either his own personal experiences, his conclusions concerning them, and, perhaps most importantly, his national policy concerning coronavirus. In a related away, rhetorically these news reports make it difficult for us to pay attention to the bodies of those who have suffered under his policies. Frontline workers, for example, who have been disproportionately affected are only present in these stories, if at all, as part of the undifferentiated mass of the national illness.

At the same time, the reader is not asked to examine the claim that Johnson makes concerning his own illness. Significantly, reports circulate around him, where Johnson never has to defend the conclusion that his weight contributed to the worse of the disease. Furthermore, some of the most sensational statements he is reported to have said ensure that reporters and others will continue to pursue the story. How much did he weigh? How much weight is too much? Tellingly, when one reporter asked follow-up questions surrounding the claim that Johnson sees the disease as easier on “thinnies,” in response, the official spokesman focused on both a national problem and an individualized solution: “As we outlined in our recovery strategy, this government will invest in preventive and personalised solutions to ill health, helping people to live healthier and more active lives.”

We are in a far cry of the feminist “personal is political” slogan, as referred to by Vivian Mayer. During the COVID-19 crisis in the UK, the solution to ill health seems to be individual weight loss. Commentators use Johnson to recommend just such a solution. As one writes, “He’s got a point and I now hope he will set an example for the rest of the nation” and “Put simply, you can talk about body positivity all you want, but obesity is a national crisis.” Imagine that front-line worker, who has been forced to expose herself to the disease because of Johnson’s policies. Rather than asking her to consider how her own personal experience underscores social injustice that makes her life all too precarious, she must, instead, be told that she is to blame for the disease.

One thought on “Boris Johnson’s Fat Body, Covid-19, and the War on Fat”