Real Men & Real Food: The Cultural Politics of Male Weight Loss

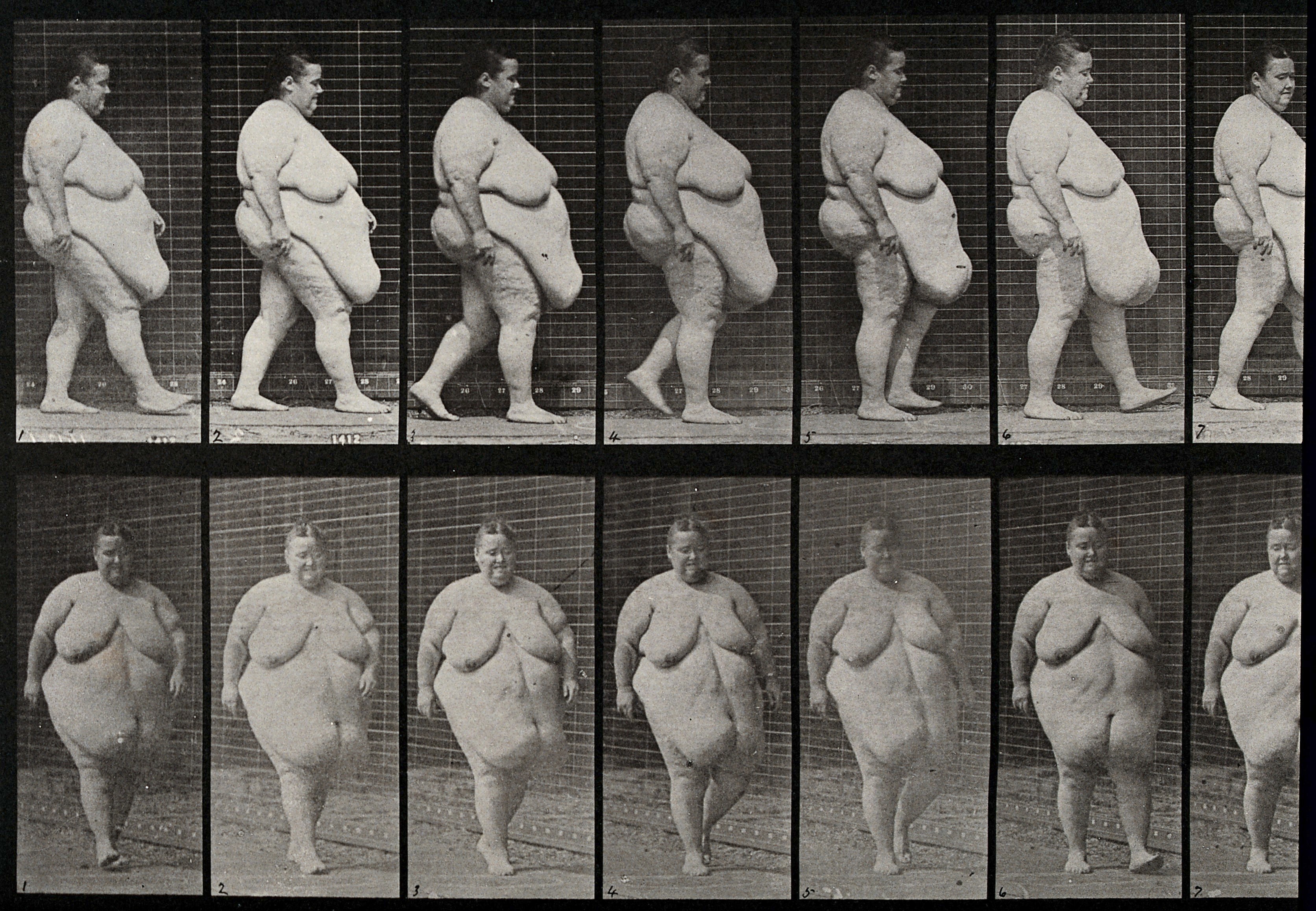

Weight Watchers first launched an online program “customized just for guys” in 2007, one of their advertisements proclaimed, “Real men don’t diet.” This counterintuitive declaration evoked the questions that animate my current research. I’m analyzing how the consumer culture constructs notions of “real men” through depictions of food and the body, particularly during moments of intense social change and anxiety. As you might have guessed, commercial weight loss programs, developed for men in the early decades of the new millennium, provide ample evidence. Men have made up a small but consistent 10 percent of the Weight Watchers membership since the company’s founding in 1963. Throughout the decades, program materials, cookbooks, and magazines have each addressed men. For example, the 1973…