The Health of Others, or: How to Be a “Good Fatty”

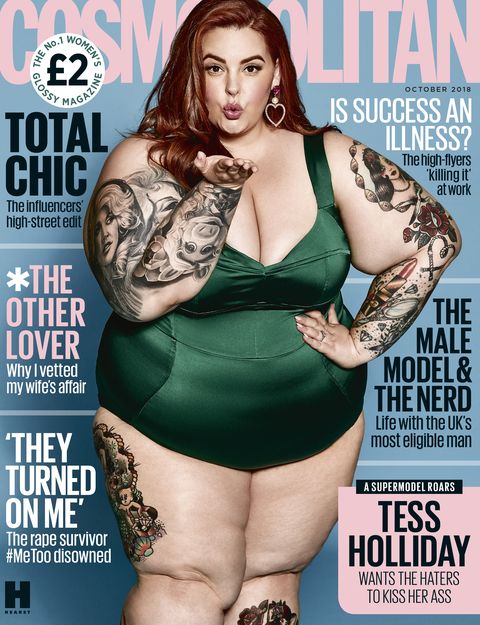

In the October 2018 issue of UK’s Cosmopolitan, “one of the busiest working models today,” Tess Holliday, was featured on the cover (Farrah Storr). The image of Holliday caused quite a stir, because this “Cosmo girl,” an iconic figure who has since the 1960s defined ideals of female beauty and attractiveness, is a white, fat woman who is shown blowing a kiss at her readers while wearing a green bathing suit. The image displays her full body, accompanied by the headline: “A Supermodel Roars: Tess Holliday Wants Her Haters to Kiss Her Ass.” Inside the magazine, writer Farrah Storr teases the article by listing that Holliday “weighs 300lbs.,” “grew up in a trailer in Mississippi,” has “suffered abuse,” and “cried just minutes” before the…