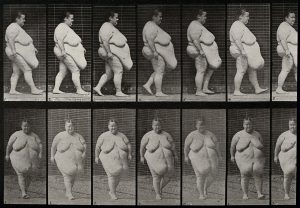

When flipping through the pages of Sander Gilman’s book Obesity: A Biography, my curiosity was piqued by the reproduction of a chronophotograph and its caption “Eadweard Muybridge, ‘A Gargantuan Woman Walking.’ Collotype (1887)[…]. (Wellcome Collection).“ Identifying the woman as “gargantuan” struck me as awkward. It led me to trace the history and meaning of image and caption, which—as it turns out—tells a lot about how fat bodies have been identified, categorized, and stigmatized in modern history.

Image provided by the Wellcome Library, CC-BY-NC 4.0

According to the Wellcome Library’s terms of use in Sander Gilman’s book “Obesity: A Biography” the image has been published with the caption “Eadweard Muybridge, ‘A Gargantuan Woman Walking.’ Collotype (1887), (Philadelphia: The Photo-Gravure Company: 1887). (Wellcome Collection).“

From 1884 to 1887, Eadweard Muybridge shot 781 chronophotographs at the University of Pennsylvania. He titled the collection Animal Locomotion, a seemingly endless series of images of people throwing a punch, sitting down, turning away, and walking, walking, and walking. Many bodies are presented almost or completely naked, in front of a grid pattern, which is familiar from anthropological photography.

The first 514 plates of Animal Locomotion show men and women. Male models were either sports students or craftsmen, women were nude models and from the lower classes. In the original catalogue, Muybridge arranged the plates according to types of movements and practices, and the arrangement is gendered in a surprisingly stereotypical manner. Whereas both women and men walk, the exercising and working body is male, while the female body is caring, graceful, and erotic.

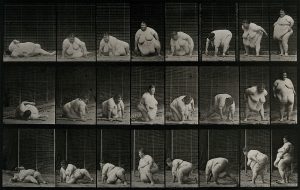

The final 219 plates of the catalogue show different animals, which are of no further interest here. However, placed between humans and animals are 27 plates in a section titled “abnormal movements:“ The photos include a boy without legs, a hysteric woman with spastic paralysis, and several more, recruited from the poorhouse of the city of Philadelphia, and set apart from the rest of the book as the “other.” The disabled body appears as lower class and as genderless, not fully human and only partly able to perform the techniques of the body.

In Muybridge’s original work from 1887, the fat woman is hard to find. She models on two plates, which are not given a special place in the collection, but integrated among the first 514 plates. The first one, no. 19, is one of 58 plates depicting people walking, simply titled “walking, commencing to turn around.“ We do not encounter her again until plate 268, in the section on lying down and standing up. In the original, this plate is simply entitled „Arising from the ground.”

‘A “gargantuan” woman getting up off the ground. Photogravure after Eadweard Muybridge, 1887.’ by Eadweard Muybridge and University of Pennsylvania. Image provided by the Wellcome Library, CC-BY-NC 4.0

Muybridge sold his plates in packages of one hundred. In the original catalogue, neither the presentation of her body nor her placement in the collection identify this model as particularly noteworthy or as belonging to a specific category, and very little information is provided about her. Bracketed between technical and other explanations, we learn that model no. 20 is unmarried and weighs 340 pounds. Tracing her by going through the long lists is somewhat difficult. No special description makes her appear different from normal, no “othering” of her body makes “the normal body” appear normal. In Muybridge’s original catalogue, she simply belongs to the people walking or arising from the ground.

When Muybridge worked on Animal Locomotion, body fat had only begun to acquire the connotation of being problematic. The historical context of both Muybridge’s work and the changing meaning of body fat was, first, the modern factory and its demand to maximize the productivity of its workers, which required detailed knowledge of the body’s anatomy and how it functioned. Second, America and the world were embarking on the age of fitness and of competition. America’s white middle classes were struck by a manic fear of weakness and obsessed with strengthening their bodies through observation, categorization, and training. They were excited by Muybridge’s project, which was funded by Philadelphia’s “better citizens.” In this context, fat began to change from a sign of success to an indicator of poor choices, with the potential to marginalize people. Slowly but surely, from everyday life to the sciences, fat was tied to laziness, passivity, and the inability to cope with the demand for constant movement in modern life. Fat was also tied to femininity, even female body cells were seen as more passive than male ones, and fat was said to resemble dead tissue, with a flabby body indicating a weak mind and moral failure. The tone was set for the twentieth century.

Fittingly, the caption, which characterizes Muybridge’s model no. 20 as “gargantuan” and first piqued my curiosity, is a 20th century invention. In 1996, the plate was renamed by an art historian of the Wellcome Library in London, most likely when the library introduced electronic catalogues and search systems for its impressive collection in the history of medicine and the body. Still, “gargantuan” is an awkward adjective and rarely used. It refers to big and grotesque bodies, and dictionaries provide “enormous” in connection with “appetite” to explain its meaning. Etymologically, the word is traced to the 1530s and François Rabelais’ novels on Pantagruel and his father Gargantua, a giant, guzzling and farting glutton. Today, use of the word to describe Muybridge’s images conveys a message of physical and moral transgression. Furthermore, calling the woman “gargantuan” is fat shaming by an art historian of the Wellcome Library, possibly with an interest in early modern Romance studies. Thus, the description of model no. 20 as “gargantuan” reveals much about the evolving history of body fat and its meaning, even if the Wellcome collection leaves the impression that image and caption had belonged together forever. Furthermore, through internet platforms such as Wikimedia and Pinterest, this combination has spread over the globe and made it into publications for academic and lay audiences.

The story continues. In December 2009 fat-activist Charlotte Cooper published a blog-post on Muybridge’s model no. 20. Combined with the description as “gargantuan,” Cooper writes, the images reduce the woman to her naked body, she is deprived of her humanity, just like the objects of colonial photographers. Described in the language of science, her “othering” is endowed with the tinge of objectivity. William Schupbach, curator of the Wellcome Collection, read and reacted to Cooper’s comments in another blog-post, reflecting upon Muybridge, fat, images, cataloguing and its techniques. Not categorizing this woman’s body seemed impossible to the Wellcome Collection, today an electronic catalogue obviously needs to serve its users’ desire to search for images of fat bodies. Yet “gargantuan,” Schupbach wrote, wouldn’t make any sense, and “why drag in Rabelais anyway?”

He replaced “gargantuan” with “obese,” which meant throwing the baby out with the bathwater. As a medical term, obese expresses the normativity and politics of health and of fat bodies as in need of treatment. Furthermore, today, health and body shape are considered to be dependent on lifestyle and individual decisions, which are judged as right or wrong, good or bad. Choosing wisely, eating right, taking good care of one’s body are part of being recognized as a productive member of society. Therefore, in the 21st century, “obesity” is as moralizing and as politically charged as the early modern “gargantuan,” maybe even more so. In the 16th century, Rabelais’ text on Gargantua is humorous, ironic, and ambivalent, in contrast to the moralizing use of “obesity” today. The obesity discourse claims absolute authority when it comes to fat, with fat presented as proof of misconduct and being unproductive, as pathological and abnormal.

Let us take a final look at model no. 20. In a 2010 coffee-table edition of Animal Locomotion, she is described as “a young woman, grotesquely obese, [who] is made to squat in front of Muybridge’s camera to help represent the genre ‘medical abnormities.’” Even though “’medical abnormities’” is marked as a quote, this category does not exist in Muybridge’s original. Additionally, the editors rearranged the order of things. The plates with our fat model are now placed at the very beginning of the section on “abnormal movements,” in the freak show between humans and animals. From 1887 to 2010, the fat woman has changed from having just an ordinary body into being the pathological prototype of the grotesque body.